Saying the Unsaid: How Writing a Graphic Memoir Helped Dispel My Family’s Shame

Margaret Kimball on Spilling Her Family’s Secrets, with Their Reluctant Cooperation

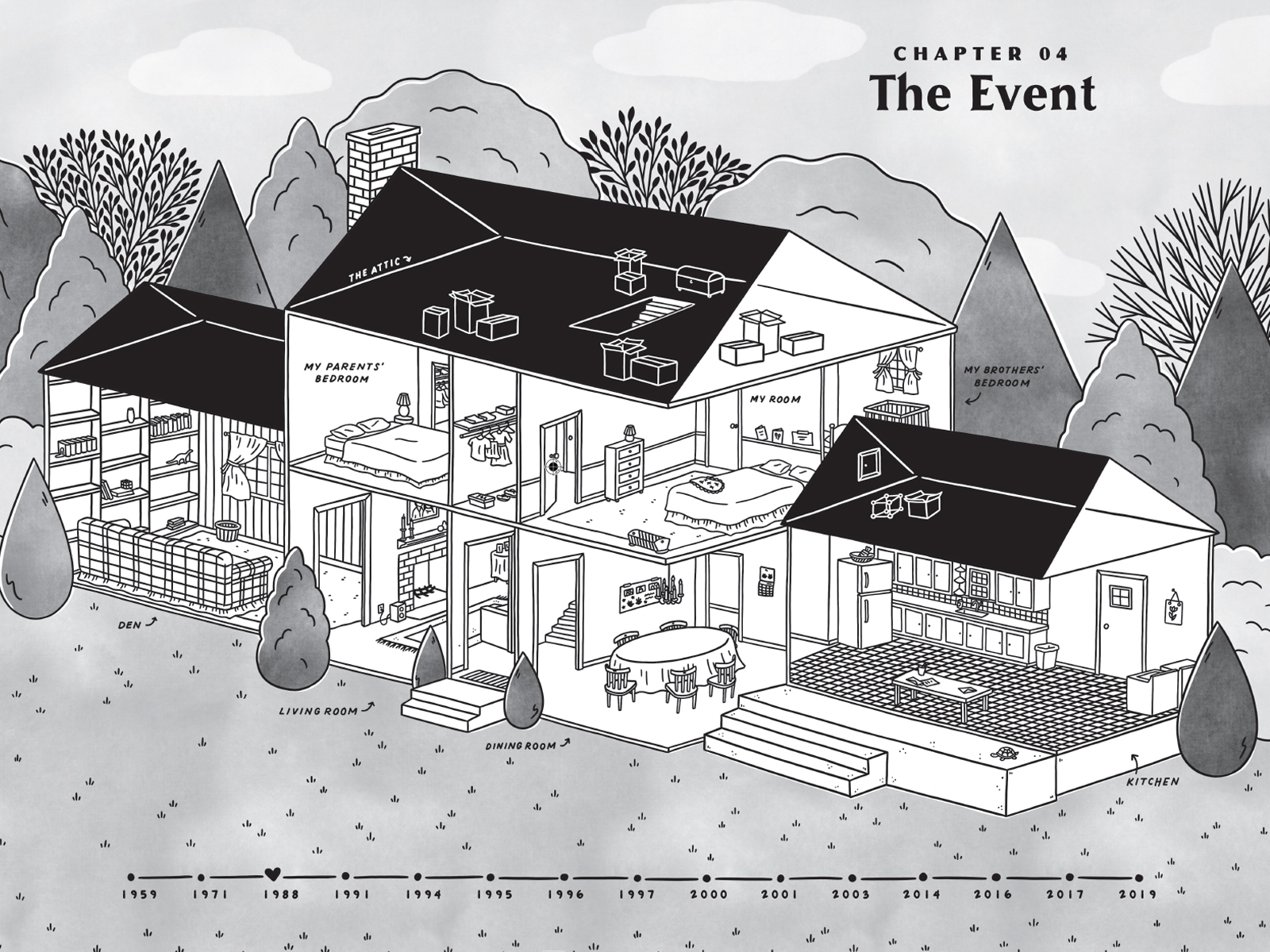

Age 19 in the summer of 2003, I got a call from my older brother that propelled me into a 17-year investigation to uncover our family’s long-held secrets. Ted said that when we were little, our mother had tried to hang herself in the shed in our back yard. Shocking information, but by then I was used to shock. Three years earlier, our mom had swallowed every pill in her possession. She’d changed her mind at the last second, called a friend, and was saved by having her stomach pumped. Ted ended with a warning, “Don’t tell anyone.” Then he hung up.

Everyone in my family knows I can’t keep a secret. Minutes after the call, I asked my dad about the incident. Had it really happened? How old was I? Why did no one say anything about it? Had it impacted us? Back then, I only knew that my compulsion to blurt was a necessary way to unburden myself. Now I understand that language creates distance, a degree of remove: rather than allowing a swarm of unnamed emotions to wreak havoc inside me, I can use words to view an event quite literally from another angle (on paper). Once I can simply say here’s what happened, that secret no longer has power over me. Writing my graphic memoir was a way for me to describe what had gone unsaid in our family. At home, my dad confirmed Ted’s story and said, “I was afraid to leave the house for years.”

After Ted’s call, I began writing about our family. I had no idea it would take nearly two decades to tell our story.

By the time I finally gathered the courage to ask my mom about her early suicide attempt, six years had passed since Ted’s phone call. She knew I intended to write about our history. Out of the blue, I dialed her up and asked about what had happened in the shed. She had no idea that Ted knew about the event, let alone that he’d blabbed about it to me. “If you write about me,” she snapped, “I’ll sue you.” After that, we didn’t speak for three months.

Writing my graphic memoir was a way for me to describe what had gone unsaid in our family.

A few years later, I wrote and illustrated an essay about visiting my dad’s apartment as a child in the aftermath of my parents’ divorce. I thought the piece was a loving depiction of how he parented us during a difficult time. I emailed the essay to him. Radio silence for a week. He finally called and said, “If you weren’t my daughter, I’d never speak to you again.”

At that point I stopped prodding. My parents didn’t want to talk and I realized that I had a choice: shut up and keep my relationships with them intact, or keep badgering and enrage them to the point of disownment. Both scenarios meant no one would answer my questions anyway so I decided to shut my mouth. In fact, I did more than that. I shoved the pages of my manuscript into a box and buried it on a shelf. Maybe I don’t need to write, I told myself.

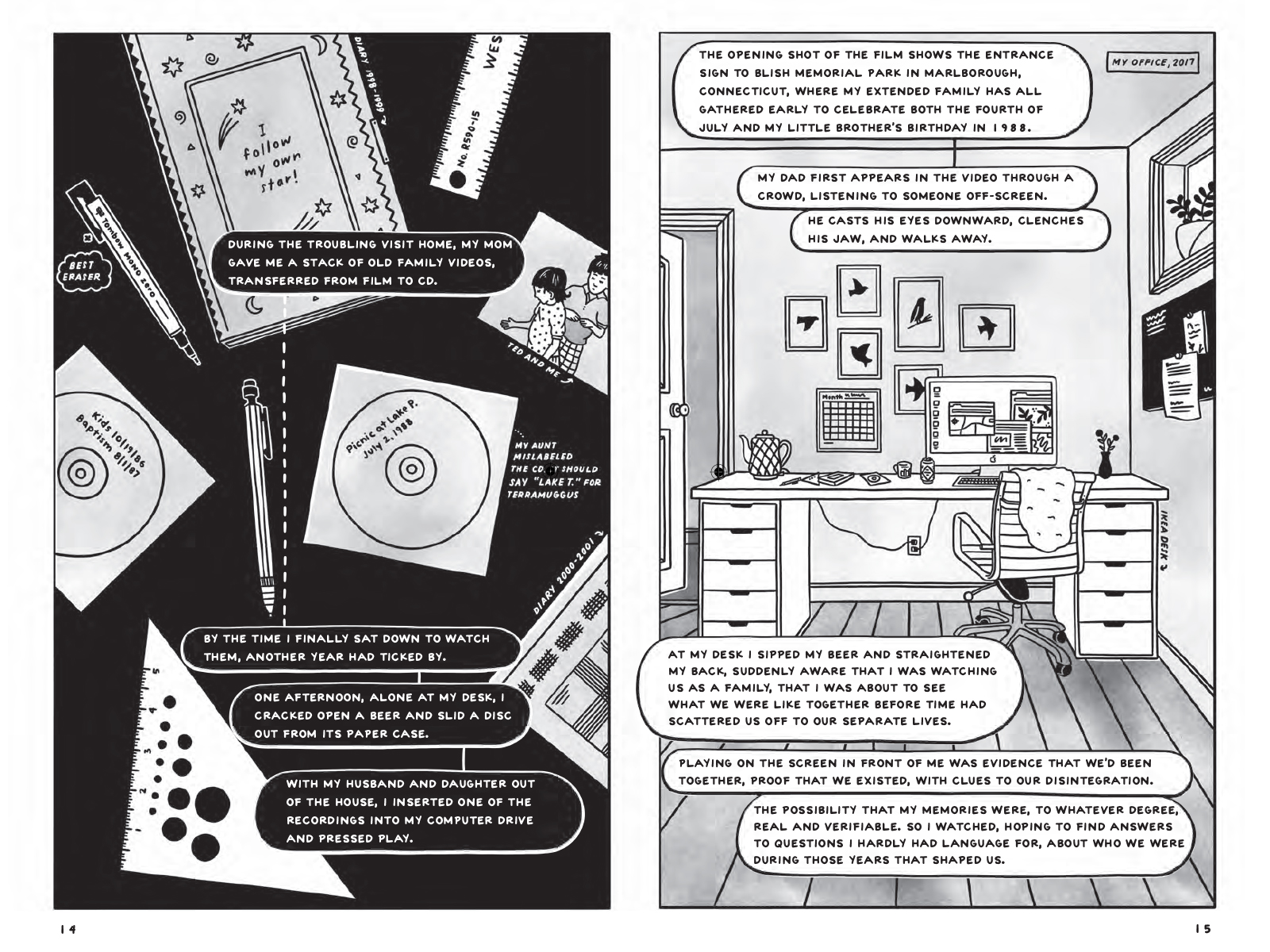

But giving up never lasted long. I was desperate to know my origin story. I soon began rifling through old diaries, photographs, and family lore, then mining my brothers for anecdotes. Slowly, I unearthed the manuscript and spread its pages across my desk. I started writing once more, though this time I kept the project to myself. Over the next five years, I pieced together a story of our past. The result was a hodgepodge of stories, mostly in chronological order, but still missing huge swaths of information.

Then a pile of records fell into my lap. During the process of applying for Italian citizenship, my mom sent me a 48-page document that included both my parents’ and grandparents’ divorce and custody records, along with birth, marriage, and death certificates, all of which illuminated a timeline of our lives. I read the divorce files first (obviously) and compared the details to what I’d scraped together in my manuscript. My parents had split up earlier than I knew, calling into further question my mom’s accusation of my dad’s affair. I rang my mom and asked her about the dates. She confirmed them and stuck to her story about the affair. But I know my mom. For her, a separation documented by the courts wouldn’t nullify the marriage or promises made therein. I revised my pages to reflect what she said, and what I believed to be the truth. I never asked my dad because I knew he wouldn’t tell me.

I became addicted to the hunt for information. Scouring public records, I found nearly every home purchase and sale my parents made, dates and prices included. Census and newspaper archives helped me locate everyone at different points in time. An archivist located the admission cards from my grandmother’s hospitalizations for schizophrenia. I pored over images of the places where she’d stayed, scanning for hints of her in the backgrounds of old photographs. Arrest records showed me nothing new—I was well aware of my grandfathers’ prison sentences—but the court schedule showed that my uncle was slated to get divorced that very day. I called my family with the gossip. By then, my parents knew about the book. Even though they weren’t happy about my probing—“How dare you snoop on your uncle!”—they were just as eager as I was for clear facts—“Who filed for the divorce? Is it finalized?”

When my mom gifted me a slew of family videos, it felt like an opening to possible conversation. One of the videos was filmed in 1988, around the time of her first suicide attempt. Realizing this as I watched, I pressed pause. Eight years had passed since I’d first asked her about the incident. The shock of my writing had worn off. Maybe she was ready to share her story.

Research provided me with specific details that formed a sort of bridge between our past and my parents’ willingness to discuss that past. When my book went under contract in 2019, my investigation into our history intensified. I wrote the first drafts of the manuscript for myself, but now I felt an obligation to readers. Talking with my family was the only way to fully understand what had happened to us, and the only way to give readers a thorough view of our experiences. Facts alone could never tell the whole story. My parents could fill in blank spots that peppered the narrative or give context to evidence I’d uncovered. I made lists of everything I wanted to ask them and scheduled a call with my mom first.

“Can I ask you about what happened in 1988?” I said softly.

“Okay,” she sighed.

“When did it happen?”

“May 8,” she said like it was yesterday. “Mother’s Day.”

My brothers and I had been at church with our dad when she ran up to the shed. There, she swallowed a bottle of pills and chased them down with vodka. Within seconds, she was unconscious. Hours later, my dad found her. At the hospital, nurses wondered aloud how she survived.

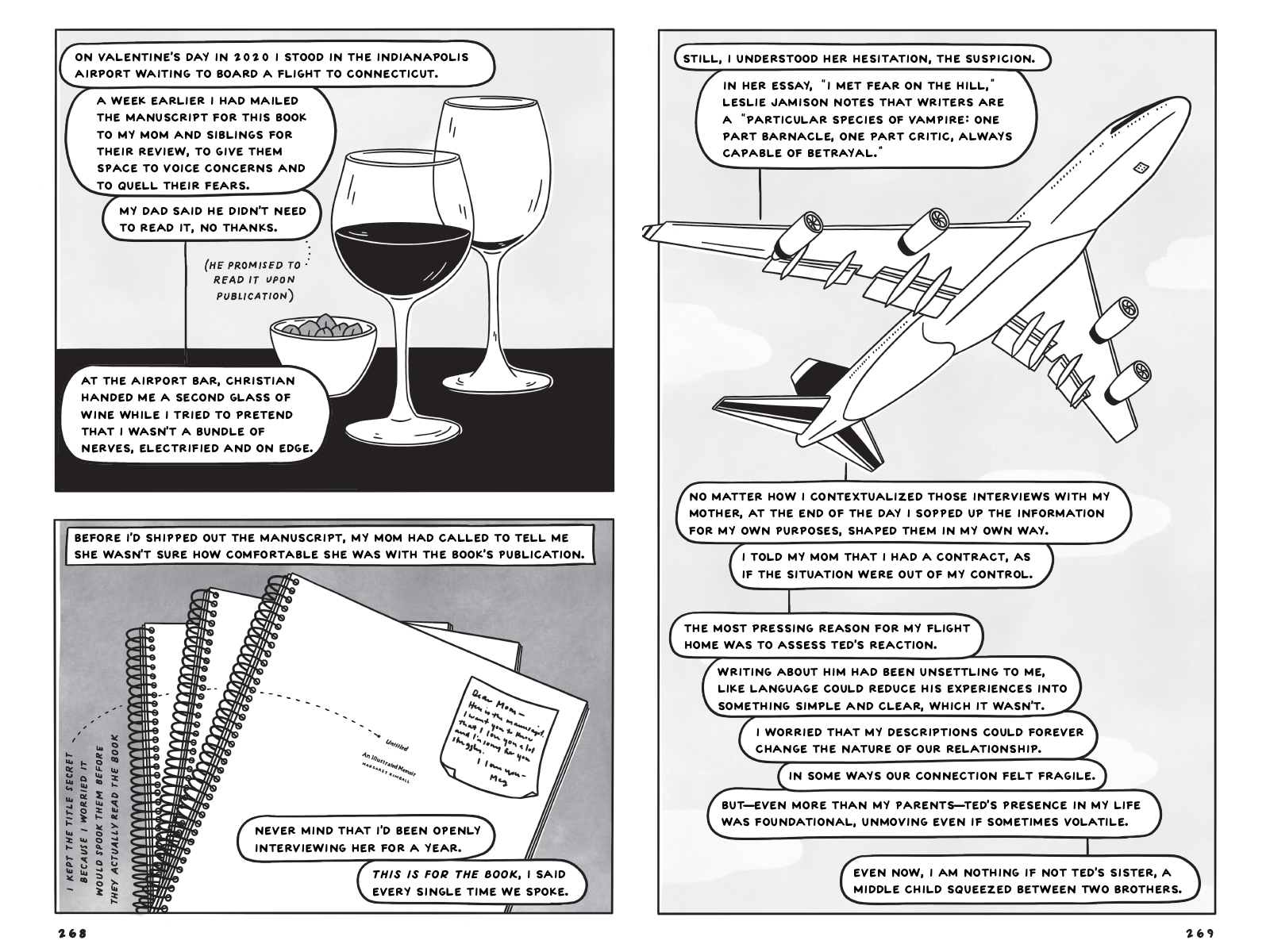

With a complete draft of the manuscript written, I flew home to Connecticut and offered my family the chance to read it and make suggestions. I wanted to be open about the project and give them a sense of control over what was said about their lives. My siblings pointed out spelling errors. My dad declined, and promised to read the book upon publication. My mom annotated nearly every page. Line by line, we discussed each item. Afterward, she seemed conflicted. While she may have felt relief at the airing of her dark past within the family—we all finally knew what happened—she also called more than once to tell me she did not approve of the book’s publication.

In some ways, the act of writing about other people’s lives is a betrayal for which there is no excuse. My method of finding solace is public, unlike my parents’ private manner of dealing with things. Our memories often differ. Even if I try to incorporate other perspectives, I’ve still stolen their histories, vampire-like, and used them for my own purposes. The words are ultimately mine, not theirs.

Secrets are a way of carrying shame. My parents would disagree with my terminology. “I’m not hiding anything,” they’ve both said. They just don’t want to drum up the past. “What good would it do?” My compulsion is the exact opposite: I want to describe our story in plain terms and conceal nothing. It’s the only way I know how to connect with other people. “Here are my skeletons; now tell me yours.” Making And Now I Spill the Family Secrets was a way for me to dispel our family’s decades-old shame, to put language to our experiences, and to let go of the past so we could heal.

_______________________________________________

Margaret Kimball’s And Now I Spill the Family Secrets: An Illustrated Memoir is available now via HarperOne.

Margaret Kimball

Margaret Kimball is an illustrator and writer whose graphic essays have appeared in Ecotone, Black Warrior Review, Copper Nickel, DIAGRAM, and other outlets. Her work has been listed as Notable in Best American Comics and she's been in residence at both Yaddo and MacDowell artists’ colonies. Her illustrations have appeared in Smithsonian Magazine, Bravery, the Boston Globe, and many major publications. She lives with her family in Indianapolis.