Saying a Few Words About My Novel at the Aphasia Self-Help Group

Jon McGregor Writes What He Doesn’t Know—But Does The Research First

“Could you just say a few words about your book?”

A hush fell over the room. Not a hush. A slight drop in the chatter and crosstalk. I hesitated. This has never been a favorite question of mine. I find it difficult to talk about my own writing. I flounder for the right words. I am inarticulate about theme and concept, about my own process, about what exactly any of my books are about. My elevator pitches ramble on long after everyone has left the elevator.

I didn’t say any of this. I held up my pen and notebook; I pointed to a stack of my previous novels; I passed a picture of a typewriter around the table.

“I’m a writer,” I say, slowly and clearly.

“A what?”

“A writer. I write stories. I’m interested in your stories. Your stories of living with aphasia.”

“A what?”

*

I’d gone to the aphasia self-help group because I was writing a novel about a character with aphasia, and I needed to know more. I’d actually been writing a novel about Antarctica, but having repeatedly struggled to describe such an alien landscape, I’d got side-tracked into writing about what happens when language fails.

Aphasia is the name given to a range of language deficits caused by a brain injury, such as stroke. A person with aphasia might have difficulty finding the right words, or constructing sentences, or understanding what is being said to them. Some people with aphasia can speak quickly and fluently without producing any meaning; others can speak clearly but haltingly, or read effectively but be unable to write, or be restricted to a few key phrases.

I knew this much from reading memoirs and textbooks, from watching YouTube videos, and from speaking to a few extremely helpful speech and language therapists. But I knew that I had no real understanding of what it might be like to live with aphasia, to struggle to make yourself understood, to look for ways of communicating around the barriers of a sudden language deficit. I knew that I didn’t know enough about how the families and friends of someone with aphasia might experience something so life-changing. I could begin to imagine these things, and fiction is at least partly a work of imagination; but, as the writer Darren Chetty put it to me recently, fiction is also a process of reconfiguration that requires knowledge and understanding to properly carry off. I was acutely aware of my privilege, as a person without experience of language deficits, in attempting to tell a story of someone with that experience.

What do you actually want to do at the meeting, the facilitator asked, when I got in touch; what do you want to know?

I’m just looking for some observations, I said. I’ll just sit in the corner and keep out of the way. I’ll just observe. It was hard to tell via email, but the tone of her response implied a slight harrumph. And by the end of the first meeting, having been asked to describe my last holiday, detail my children, and having come joint first in the general knowledge quiz—and having spent a lot more time laughing than I’d anticipated—it was clear that passive observation wasn’t how this was going to go.

*

The Aphasia Nottingham “Coffee & Conversation” group meet monthly in a community centre not far from my home in Nottingham, England. (Or they did, at least, before the pandemic; currently their meetings take place online, and you really haven’t seen Zoom chaos until you see Aphasia Zoom chaos.) Paying their dues on the way in, and collecting their name badges, the members of the group took their places around a large meeting table; around a dozen of us, usually, although people came and went. New faces appeared; others disappeared. There were people with aphasia, and sometimes their partners or carers. There were two speech and language therapists, who were there to facilitate-but-not-run the sessions, and the occasional student observer or socially-awkward novelist.

Each month the chair of the group would welcome us all, go over any unfinished business, and introduce the morning’s topic—a physical difficulty in forming word sounds, quite distinct from the neurology of aphasia—and his wife interjected as little as she could bear. (This dynamic, of partners being torn between wanting to assist communication and wanting to give the person with aphasia the time to speak for themselves, was in constant and fraught flux. It was one of the things I took note of, and felt guilty about taking note of.)

The quandary that was nagging away at me: when most of the people at these meetings could no longer read, how would they know if I’d told their story properly at all?

After the introduction, the group took turns to check in: a flashcard with a range of emoji faces and a selection of clip-art activities was passed around, and everyone shared both their current mood and what they’d been doing recently. The ritualized nature of this was only emphasized by the fact that everyone, without fail, would point to the smiling emoji and claim to be “happy,” or, in the emphatic Nottingham accent, “appeh.” There was more variety with the ‘recent activity’ report. Someone would point to a clip-art icon and announce what they’d been doing in a single word, prompting a kind of charades game in response.

“Friends.”

“You met up with some friends?”

“No, me. Friends. House.”

“You went to your friends’ house, is it?”

“No. No, no. Me. Home. Friends.”

“Some friends came to your house, to visit?”

“That’s right, yes.”

“Did they stay over?”

“Stay? Oh, no!” This said with a horrified expression, and a laughter that soon filled the room along with a racket of cross-talk and suggestions as to why those friends hadn’t been invited to stay.

The whole process took quite a while. By the time the introductions were done it was almost time for the coffee break.

*

I never took notes at these meetings, although I occasionally rushed home to do so. I felt self-conscious about my role as an observer, and ambivalent about what I was taking from these people for my own benefit. There is a troubled history of people who look like me—white, male, able-bodied, economically secure—taking from the experiences of various people who don’t look like me and “telling their story,” often without permission, often without sufficient understanding, and usually to their own benefit. I didn’t want to claim an expertise I could never have, but I wanted to understand as much as I could.

I didn’t want to simply reproduce the people I was meeting in this group as fictionalized versions of themselves—to hold them up to the light for a reader’s fascination. I felt as though I owed them their privacy. I had characters and storylines in mind before I ever attended a meeting, and was looking instead for nuances of voice and expression, for the many complexities of communicating with limited or little language, for—as it turned out—how easily people could still, without words, make each other laugh.

And I was told, over and over again, by people with aphasia, by their families, and by the speech and language therapists I was talking to, that they were glad I was writing a novel about aphasia: that people didn’t know about it, that they wanted their stories told. Which was nice to hear, of course. People like to feel that they’re doing a good thing, perhaps writers more than most. But it didn’t really solve the quandary that was nagging away at me: when most of the people at these meetings could no longer read, how would they know if I’d told their story properly at all?

*

There was a lot of talking at the group meetings, which was perhaps unexpected. There was often so much talking that the planned business was never quite got through. The meetings were short, by necessity—grappling for language is exhausting, it turns out, which is also why the meetings were always in the morning, when people were more likely to have the energy. There were often conversations going on in the margins, and this was where I best got to know people.

I had a long and inconclusive chat with G, who told me about a trip he’d gone on by pointing at Google Maps on my phone. His sentences were full of conjunctions and prepositions, with the content never quite arriving: “And then so of course, you see, what we did then was, we were going, going, so, until, and then, car, before.”

I talked to C and S about their trips to the eroding coast of Norfolk, where I grew up, and about how they’d had to sell their holiday home because it was on the verge of collapsing into the sea. C had a particular facial gesture—a skyward glance, a puff of the cheeks, a whistle—that very evocatively conveyed the sense of peril felt on a stormy night beside an eroding cliff.

There were lots of these side-conversations during the meetings, but somehow the chair managed to keep bringing the group back to that month’s topic. A map of the world was produced, for people to planted post-it notes on countries they’d visited and attempt to talk about their visit. A musician was invited in, and led the group in a half hour of singing, three-part harmonies and all. And then one month the topic was books, and it was my turn to speak.

*

I had read up on “aphasia-friendly communication,” and had learnt a lot from my time with the group. I knew it was important to keep my remarks brief, to speak clearly, and to use a range of visual aids. I should keep my sentence structure simple. I should avoid multiple clauses. I should use names in place of pronouns as far as possible. I should avoid simile, metaphor, and other indirect language. I should avoid the passive voice. (And yes, the overlap with generic MFA workshop advice was striking. I knew that Samuel Beckett had written some of his very late work while affected by a type of aphasia, but I was starting to wonder about Carver and Lish.)

My talk was preceded by each member of the group introducing their own favorite book, which they did with enthusiasm and with the caveat that on the whole they could no longer read more than a page or two, and that books were beyond them now. This was hard to hear. Partly, this was what had drawn me to writing about aphasia: a terrified fascination, the awful sense of what-if? I had heard of a novelist, a friend-of-a-friend, who had had a stroke shortly before the publication of his third or fourth novel, and attended his own book launch in silence.

And while I didn’t want this writing project to turn into some kind of mawkish rubbernecking, I was deeply troubled by the thought of having language—my primary means of engaging with the world, the core of my profession and my identity—stripped away from me. Looking around the room at these people holding the books they had once loved and could no longer enjoy was quite something.

“I’m a writer,” I started.

“A what?”

*

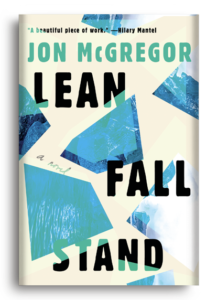

When I started writing the novel that would become Lean Fall Stand, I had something deeply Beckettian in mind; a text that would inhabit the mind of someone with aphasia and represent that experience quite literally, with all the elision and error and absence that would entail. It would be virtually unreadable, I imagined, but would achieve something impossible: it would boldly venture into unmapped territory, capture something essential, and bring it home for the non-aphasic reader. If I thought about it hard enough, I assumed without really thinking, it through, I could find a way to reproduce or mimic the interior experience of someone with aphasia.

After the first few meetings of the Aphasia Conversation group, I realized just how wrong-headed this was. Meeting these people, and forming connections with them around the very real hurdles of their language deficits, showed me just how unknowable the interior experience of living with aphasia really is. I could no more venture in there and capture it than I could write about an Antarctic landscape I had never even been to. What I needed to do, I realized, was to take a step back and listen. And I needed to give the reader that opportunity to stand back and listen; to show them a group of people struggling with their communication, looking for ways to connect while working around their aphasia.

Which is all a long way of saying: I decided to write in the third person instead of the first. Being a part of the Aphasia Conversation group had shown me what it might mean to be alongside someone with aphasia; it could never show me what it meant to be someone with the condition.

*

The talk went well, I think. My line drawings of penguins and Antarctic explorers were appreciated, once I’d explained what they were. I said that when I’d come back from Antarctica I’d had great difficulty putting the experience into words. I said that I was interested in what happens when words are not useful. I was writing about a character who has a stroke while working in Antarctica, and about how he and his wife adapted to life after stroke, and to living with aphasia. That’s why I’m here, I said. I’d like to know more about what it’s like to live with aphasia, and how you get on with your lives.

People seemed interested in my interest in them. I kept my remarks brief, and avoided the passive voice. I told them I was making good progress with the book, and I would finish it in another year or two. I told them I was learning a lot from them about living with aphasia, but that I wouldn’t be putting them in the book. I’m not here to steal your identities, I joked. When I’d finished talking, they thanked me. That was interesting, they said. Good luck with the book, they said. What they didn’t say, because for most of the people in the room this was by definition no longer an option, was that they were looking forward to reading it. Instead, in the space where people might usually say something like that, there was silence. Eye contact. Half a smile.

___________________________________________________

Lean Fall Stand is available now from Catapult.

Jon McGregor

JON McGREGOR is the winner of the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, the Costa Book Award, the Betty Trask Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters E. M. Forster Award, and has been long-listed three times for the Man Booker Prize, most recently for his last novel, Reservoir 13. He is professor of creative writing at the University of Nottingham, England, where he edits The Letters Page, a literary journal in letters.