Save or Shred? On the Allure and Conundrum of Unpublished Novels

Randee Dawn Explores Approaches to Trunk Fiction

Is this your first novel?

Every author, at some point, fields this question. The non-writing world—encouraged up by Hollywood’s take on how the life of the author works—has been left to believe that publishing a book looks like this: Get inspired. Write the book (in approximately two months). Show the book, receive ecstatic encouragement. Achieve agent, achieve publisher, book comes out (again, to ecstatic encouragement). Rinse, repeat.

Here’s the truth: Most authors do not publish their first novel. Writers have a string of almost-rans, never-completeds, and works that never found publishing homes.

Regardless of where these works are literally kept, they’re referred to as “trunk” novels. Every author has one, two or ten, and they’re often only discovered posthumously.

Franz Kafka took pains to set many of his old works alight and entreated his friend Max Brod to scorch the rest after his death. Brod disobeyed those orders, which led to the publications The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika, among other works.

Authors have limited choice over what happens to their unpublished work after their deaths—but while they still live, the decision over how to treat their trunk works is as individual as the authors themselves. Given enough time every writer develops some trunk oeuvre.

Words pile up in the early stages of a writer’s career when we’re writing for ourselves and have no idea anyone will ever read what we’re writing, much less want to publish it. We’re pumping out works as assignments in MFA programs, learning from professors and writers groups and also doing plenty of self-instruction.

I’m an author with my own trunk novels, but something surprising happened recently: Two of them, The Only Song Worth Singing, and Leave No Trace, found homes decades after they were originally written. They have versions that have been “trunked” on everything from notebook paper to floppy discs to the digital cloud. I even have an old dot-matrix printout of an early take on one.

As authors mature in their writing and their personal lives, many find ways to rediscover their trunked works. Stephen King has been reaching into his trunk drawer for many years, and is open about early versions of two of his novels—11/22/63 and Blaze, which were started or even completed decades before they were published.

Of course, King’s mass acceptance across both genre and mainstream fields means he probably can get published whatever he wants to have published; when he passes away, it seems unlikely he’ll have any works left in his trunk.

“I cannot fathom a trunked novel,” author Jonathan Brazee told me recently. “To me, that’s like having a child for whatever reason you keep locked up in the basement never to see the light of day.”

Even when a story doesn’t come up to an author’s standards, he adds, it’s still worth getting it out into the world—perhaps under a pen name. “You, as the writer, can get the satisfaction that someone will read it. And there will be a reader out there who will read and enjoy it, enjoyment that they would otherwise never have.”

There can be practical reasons for avoiding a trunked work, though. Bestselling author Caitlin Rozakis told me that she has two stories “whose subgenre went out of fashion.” They’d take work to “bring up to my current standards.” But “if either the subgenre seems to be coming back or my current line of inspiration runs dry, I may cycle back at some point.”

Which brings us to the other—more likely—end result for a trunked story: To be raided for its juiciest parts. When I decided that Song and Trace were likely to never seen publication in their full form, I combed their plots and characters for stories that could exist outside the novels, or characters who deserved a second chance at life.

That worked: my antagonist from Song now also lives in the novella Rough Beast, Slouching. Meanwhile, stories from the universe that connects the two novels have been published in anthologies and magazines over the years.

Writers are magpies, after all. We take the shiny bits from our lives to write stories, so it’s a natural choice to re-acquire the untarnished bits from finished works that haven’t found a place to call home.

Critic and author Alec Nevala-Lee had a first-draft of his novella “The Elephant Maker” (published in 2023) that was 225,000 words long. It got him an agent, but there was no way to wrangle that pachyderm into a useful novel. Many years later, he took the sections that still spoke to him and made a thirty-six-thousand-word version, published in Analog Magazine.

Other authors I spoke to about trunk novels suggest they’ve done similar things: Amanda Ratchford Cherry says she “mines them for content,” noting that “pretty much everything I have written has something in it worth resurrecting from the scrap yard.”

But those who fail to find a way to erase their unpublished works before they leave this earth run the risk of those works getting into the world despite them, a la Kafka. Author Simon Ings spoke in Locus in 2015 about his wife being the agent for Lawrence Durrell’s estate; Durrell, he noted, threw away an enormous volume of work—but only figuratively.

“The house is full of bad Larry Durrell, and the agency and the state are constantly turning down these academics [who want to publish it],” said Ings. “The only reason he didn’t discard it in a bin is because he’s a writer and he might need the scene later. That’s part of the writer’s job.”

To publish or to burn? To mine or to let languish? That, as Ings might suggest, is also part of the writer’s job. But writers and the publishing industry are fickle creatures. What “works” one year might be out of style the next; what seems like an awful concept can have the seed of a future bestseller. The urge to keep everything just in case is hard to deny.

Of course, in announcing that two of the novels I’ll get published this year are not just old but very old I run the risk that someone will say, “I can see why this didn’t get picked up before.” Maybe they are only “aggressively meh,” as Rozakis characterized another of her trunked novels. The court of public opinion hasn’t yet convened.

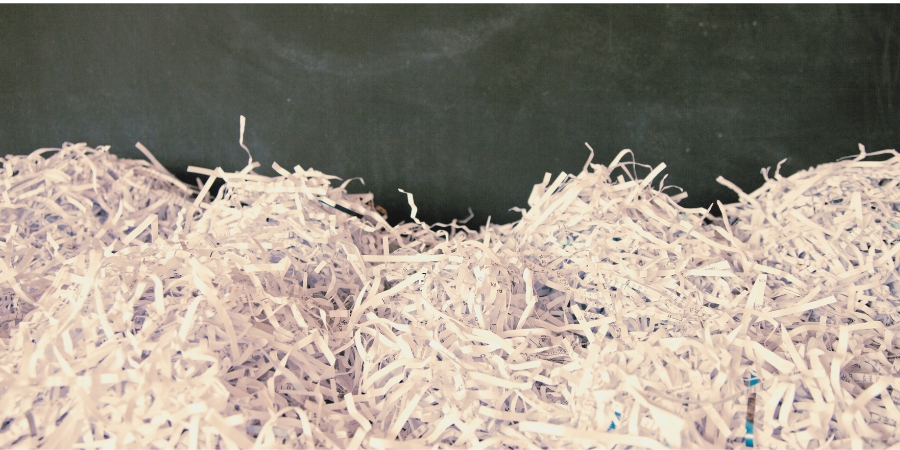

Then there are authors like eight-time Stoker Award finalist Scott Edelman, who says he’s shredded thousands of pages of his unpublished poetry, short stories and early novels. He doesn’t even keep backup digital copies for them. “I’m glad to see them gone,” he says. “I want only my best to survive, and am doing what I can to keep anything less than my best out of the hands of future archivists.”

He’s clearly had a meeting of the minds with William Carlos Williams, who once wrote,

It is dangerous to leave written that which is badly written. A chance word, upon paper, may destroy the world. Watch carefully and erase, while the power is still yours, I say to myself, for all that is put down, once it escapes, may rot its way into a thousand minds, the corn become a black smut, and all libraries, of necessity, be burned to the ground as a consequence.

Of course, in announcing that two of the novels I’ll get published this year are not just old but very old I run the risk that someone will say, “I can see why this didn’t get picked up before.”[/pullaquote]Which brings us back to the question authors often get—is this your first novel?

The answer is almost certainly no. Novels, stories, essays and other works don’t fit into neat cubes like that. They can be inspiration for later works, or they can molder on their own inside a digital system, a file cabinet or a literal trunk.

In time, a first novel can have a chance at a second life. But that only happens if authors avoid the burn pit or the shredder. Meanwhile, Edelman is happy to see his trunked works find new life—as he puts it, as “confetti.”

______________________________

The Only Song Worth Singing by Randee Dawn is available via Caezik SF & Fantasy.

Randee Dawn

Randee Dawn is the author of many books, including Tune in Tomorrow, The Only Song Worth Singing, and Leave No Trace. She is a Brooklyn-based author and journalist who writes speculative fiction at night and entertainment and lifestyle stories during the day for publications like The New York Times, NBCNews.com, Variety, The Los Angeles Times, and Emmy Magazine.