Unless you knew what you were looking for, you would never see it in him. Even I, in full possession of the facts, had to observe him very closely that New Year’s Day evening of 1820 when he arrived at Upper Seymour Street before I noticed something in the hair and lips and that slight tinge to his skin. In all other respects he was my brother’s son—a slightly younger, taller version of Robert as he had been when he came to see me on the docks as one of the ships was about to set sail and said he would like to be apprenticed to the ship’s physician, and was prepared to leave right away. That was the last time I saw him—more than twenty years ago.

England didn’t please him, the boy, my nephew, Charles; that was evident immediately. But England pleased no one that winter, all frost and snow and discontent. I made clear to him that first evening the terms under which he was to live with me: he was my heir, but not my son. I had never sought a family of my own, and though I recognized my responsibilities to my late brother’s only child I wished to be allowed to live my life with as little disruption as possible. He was welcome to my library, and to join me for supper, but beyond that he would have to find ways of occupying himself for the next few months until he turned sixteen, when I would purchase a military commission for him. He agreed readily, thanked me with perfect manners, and asked if he might pull up a chair closer to the fire. Winters were never like this in Jamaica, he said, and I told him winters were never like this in England, either.

“How so, sir?” he said, and I saw he understood I didn’t only mean the weather.

I could have explained to him then the strange mood that had the country in its grip, for which the best explanation I had heard was that the sick, mad king in Windsor had infected the entire realm. Not for much longer, if the stories were to be believed, and perhaps then this mood of restlessness, of something near revolution—though not that, please God not that—would pass. But it was late, and the fire was burning down, so I said it had never before been so cold for so long, and showed him up to his room.

In the weeks that passed, he became a welcome presence. In the mornings we sat together by the fire, slowly picking our way through The Times and the Morning Chronicles, and he read the Tory and Whig view of events in England, and heard his uncle’s commentary on both. There would be a period of reading in the library after that—he had a particular taste for my books of history—and at some point, earlier or later, he would bundle himself into all his layers of clothes—he had seemed so genuinely surprised when I sent for my tailor that I wondered if he expected me to allow him to go through an English winter with only his father’s old coat to keep him warm—and disappear until supper. I never asked him where he went. I did not like him to know how much I had started to wonder about him, and his life.

What I wondered most was if he knew who—what—he really was. My brother had mentioned it only once, in an anguished letter which was followed speedily by another asking me never to mention it, never even to remember it if forgetting such a thing were possible. “The matter is settled. He is to be raised as Charlotte and my son. We are going from here to a place where no one need know that there is anything else to the story. Charlotte says it is a mark of God’s wishes for the boy that he looks entirely my child and no one else’s.”

England didn’t please him, the boy, my nephew; that was evident immediately. But England pleased no one that winter, all frost and snow and discontent.It’s possible, I expect, that I suggested we go to the theatre together to watch Mr. Kean in Othello despite the bitter cold because my curiosity wondered if his response might reveal something. He agreed readily enough, and sat beside me through the play, responding in his gasps and his applause just as any Englishman would. But when we left the theatre he said, “Othello was not as I imagined him when I read the play.”

“In what way?” Mr Kean played a lighter-skinned Othello than any that had been seen before, and I assumed this was what he meant.

“Less intelligent. There was nothing to him but passion, and savagery.”

I knew then that he knew who he was, and I was filled with shame for what I had done. “He could hardly play him as an English gentleman.” I touched his shoulder as I said it, to let him know that I considered him an English gentleman. He smiled in agreement, and I was surprised by the extent of my relief.

The weeks passed.The temperature rose above freezing.The mad king died. I waited for the world to right itself. But instead a group of radicals, including one William Davidson—a black man from Jamaica—were arrested at Cato Street for their part in a ridiculous and grotesque conspiracy to behead the members of the cabinet. By now, I was so accustomed to seeing Charles simply as Robert’s son that I didn’t think he would have any specific interest in this Davidson, a man of unmistakable blackness who showed no sign in his countenance of his English father. Charles certainly did not mention him particularly when we read about the events and I expressed satisfaction that the ringleader, Thistlewood, had been captured after initially making his escape.

He did ask me why I thought the men wanted to do something so violent and extreme as beheading all the members of the cabinet and I told him there were always men who stood ready to commit acts of violence against their betters, and we must be grateful for those who remain vigilant against such radicals and save us from them. He seemed satisfied by this response at the time, but later, over supper he said, “Do Peterloo and the Six Acts have nothing to do with this?”

I knew by now that some of his wanderings took him to coffee houses where there were conversations and newspapers such as would not be found in Upper Seymour Street. It came as no surprise that in these places such views would be aired, and I was pleased that he had come home to me to set his thoughts straight.

When repression and injustice leaves men with no recourse but to take drastic measures to throw off the chains that bind us—then, Uncle, what then? Is that savagery?I said I had never defended what happened at Peterloo. No doubt it was true that the intentions of the speakers at that public event was to ferment disorder but even so, the Cavalry should not have responded so overzealously, and without reprimand. The deaths of those English men and women should not have gone unpunished. But it was necessary to understand how perilous a state we were in. Radicals—such as Thistlewood—were everywhere, seeking to exploit the unhappiness of the poor, and they would have used Peterloo to stoke many fires if the government had not responded with the Six Acts, limiting the Radicals’ power to hold meetings and publish fiery tracts. “It is stability that matters, Charles, do you understand?”

He nodded very seriously. “I do, uncle,” he said, fervently.

More time elapsed. Spring came and as the days thawed and lengthened my boy was out more and more hours than before, often coming home with the stink of the public house attached to him. But we always supped together, and he was always courteous and sweet-natured. I had begun to wish I had never offered to buy that military commission—all those years ago, I thought I was helping his father to propel himself forward into the world, but I only propelled Richard away from me. He took to the life of a physician, but not to one at sea, and when my ship anchored in Jamaica he chose to stay there, away from any influence I could have brought to bear on his life. Perhaps, I said one evening to Charles, as though it were a minor matter, perhaps given his taste for reading he would prefer university to the military. A man of letters, why not?

He smiled his perfect courteous smile, thanked me for the offer, and said he would consider the matter.

This was, if I’m remembering correctly, just a few days before the conspirators of Cato Street were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. We read the news together on an April morning, with the birds singing in the trees outside.

“Of course they must die,” I said. “But it seems unnecessary to bring back such a medieval way of doing it. An axe would do the job just as well, and with less savagery.”

“Because Englishmen aren’t savage.” He said it so mildly I didn’t even look up, and only made a noise of assent. I was barely aware of him leaving the room, or of the sound of his footsteps climbing up the stairs and then striding across his bedroom which was directly above where I was sitting. When he returned he sat down again, and leaned forward, his elbows on his knees, and waited for me to look up at him before he started to speak.

“When the Cavalry massacred Englishmen and women gathered peaceably in a field to hear a speech, that wasn’t savagery. When the government said they had done nothing wrong, even though they didn’t read the Riot Act first, that wasn’t savagery. When the rich live in gilded palaces and the poor die of starvation, that isn’t savagery. When Parliament is corrupt and resists reform, that isn’t savagery. When laws are passed to prevent Englishmen from gathering together to speak their mind, or to publish their thoughts, that isn’t savagery. But when all that repression and injustice leaves men with no recourse but to take drastic measures to throw off the chains that bind us—then, Uncle, what then? Is that savagery?”

All this in a quiet tone, without any emotion, and the last question asked in that familiar tone from every morning when we read the newspapers together—the tone of one who wants to learn from his uncle. Only now did I see the mockery in it. “It is savagery. And to defend such acts is savagery too. I don’t know what company you’ve been keeping, my boy, but I must ask you to quit it.”

“Do you think Davidson, the man of color, was more savage than the others?”

“I have never said such a thing.”

“There is so much you don’t say, uncle. So much you don’t ask.”

“You are a child. What should I ask of a child?’”

“Ask me on what terms my father’s wife agreed to raise me as her son.”

He stood and walked towards the window, and opened it though the early morning was cold. “Even those who are sympathetic, who think the Cato Street conspirators had cause, even they never stop to think that perhaps Davidson had more cause than others. Perhaps he knew who you are better than you do.”

“Close the window, and stop this nonsense.”

He turned to face me, and the trees threw their shadows on his face, darkening it. He held out his hand, and I saw it had a piece of paper in it.

“What is that?”

He hesitated. It was almost as if he thought I would get up from my chair and walk over to him.Then, in a few steps he was beside me, pressing the square of newsprint into my hands. I read.

TAKE NOTICE, That on Monday the 16th day of July, I will put up to Public Sale, at the City-Tavern, in Kingston, between the hours of 10 and 12 of the clock in the forenoon, a Negro Woman Slave, named SARAH, a House-Servant.

“My father kept this” he said, still in that tone without emotion. “I found it when he died. It was his wife’s condition for raising me. The night after the funeral of the woman I called ‘mother’ my father spoke to me of the other one—of Sarah. He was not without feeling for her, it seemed. But as you once said, it is stability that matters. All English gentlemen, and those who aspire to be them, know that. Look at the date.” He tapped his thin tapered fingers—not Richard’s fingers—on the paper in my hand. “I was born on the 12th of July. I wonder a great deal about those four days before my father sold my mother. Do you think they allowed her to spend any part of those days with me?”

I bowed my head. I could not look at him. He returned to his usual chair and picked up the newspaper that he had earlier discarded. “What do you think will happen with the matter of the king’s divorce?” he said, amiably.

“You are in my house, sir!” I said. “I feed you, I clothe you, I have offered you any future you want. I give you all my affection. Why do you treat me so poorly? I had no part in the decision made by your father. I never knew of it until now.”

“Do you think my father would confess all this to me, and not confess the basis of his brother’s fortune?”

“I was born on the 12th of July. I wonder a great deal about those four days before my father sold my mother. Do you think they allowed her to spend any part of those days with me?”It was almost a relief to have it out between us. I stretched out a hand to him. “I supported the Abolitionists. I sold my ships almost fifteen years ago…” Soon after I had news of your birth, I almost said, before I stopped myself. He knew his own age.

“When you had wealth enough to last a lifetime, and the abolition of the slave trade was a looming inevitability.”

“When I saw the wickedness of the practice. When I was convinced of it by those who wanted reform—and who used the words of morality and godliness and enlightenment to convince. That is how reform comes about. Not by butchering the Cabinet and placing their heads on pikes and displaying them on the street as these foul men of Cato Street planned to do.”

“The same men whose butchering will be a public display by the orders of the government. And meanwhile, slavery carries on unchecked in the colonies, and England profits from it.”

“That will end, too. The Abolitionists are tireless. I support their cause. Financially, you understand. I am not unaware of my…responsibilities.”

“A few conspiracies to behead slave-owners might be more effective in speeding up reform than the tirelessness of the Abolitionists, or your attempts to buy your way into heaven with the wealth you mined in hell.”

I could not read his expression. I knew nothing of his character, or of what he might be capable. I had thought he would be my salvation, but I understood, then, that if my wealth had come from the mines of hell, so had he. And like Prospero at the end of the The Tempest there was nothing to do about my Caliban but say, This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine.

I rose from my chair. “Enough talk. Mr. Milton awaits me in the library. And who awaits you? Mr Gibbon?”

“I am finished with him,” he said, standing up. “Today will be something new.”

He followed me into the library, his tread soft, almost soundless.

__________________________________

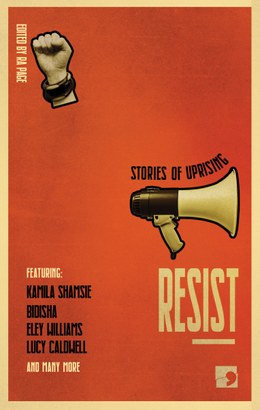

Resist: Stories of Uprising edited by Ra Page, is published in paperback by Comma Press and available in the US from the 1st April.