Sara Franklin on the Powerful Unsung Legacy of Edna Lewis, A Great Southern Chef

Chef Diep Tran Talks to the Editor of Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original

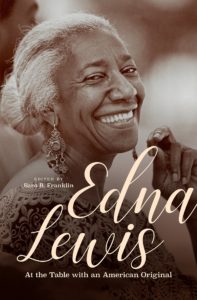

Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original (University of North Carolina Press) was published in 2018, and was released in paperback February of this year. Sara B. Franklin, the editor of the book, and Diep Tran, a chef and food writer, talked about the enduring, yet largely unsung, historical legacy of Miss Edna Lewis, as well as the renewed relevance of her work and beliefs in 2021.

*

Diep Tran: Firstly, congrats on the paperback edition of Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original!

Sara Franklin: Thank you so much!

DT: I’d love for you to talk about Edna Lewis’s enduring legacy and the ways in which her work still resonates with us today.

SF: Oof, a doozy of a question.

DT: I know.

SF: I think the first thing that folks have got to understand is that Edna Lewis had a legacy, but only a very quiet one, until very recently. Though those who knew about her—a Black woman born the granddaughter of formerly enslaved people—loved and celebrated her cooking and, later, her writing, she was not widely known in American popular culture or even in the food world. And though her legacy has had something of a resurgence in recent years, she’s still a largely unknown figure. Even those who do know about her often only know bits and pieces of her life and work that are heavily mythologized

The two most popular touchstones of her memory are the publication of her 1976 cookbook, The Taste of Country Cooking, which she did with Judith Jones as her editor at Knopf, and her swan song as a professional working chef of Brooklyn’s Gage & Tollner (when, by the way, she was a WORKING CHEF in her seventies).

DT: Yes, for those of us who are admirers of her work, Edna Lewis looms large. For the general public, she didn’t get anywhere near the shine she deserved. And that she was still working in her seventies is astounding.

SF: Also, very few people know about the larger story: the fact that she was both chef AND partner at Cafe Nicholson, a restaurant on Manhattan’s east side beginning in 1949. Or that she returned to domestic service after that restaurant closed and her marriage ended. Or that she was really taken advantage of financially when she worked as a consulting chef in the Carolinas in the 80s. So even her working life—the part of people’s biographies we often know best—is veiled in mystery. She was a caterer, yes, but not successful until later. No, she struggled financially all her life. The correspondence I’ve read between her and Judith Jones—some in Judith’s personal papers, and some in the Knopf files—reveals how persistent and how, at times, desperate her economic situation was.

DT: I knew that she was a partner at Cafe Nicholson, but I didn’t know about her returning to domestic work. This fact hurts.

SF: It does. It lands with a thud.

DT: Let’s talk about myth vs. fact. What is the myth?

SF: The myth is that Edna Lewis was a sweet, soft-spoken Black southern woman who was grateful for all the chances she was “given” after she left her hometown in Freetown, Virginia. That Freetown—her childhood home in Orange County, Virginia, where she was born in 1916—existed as a perfect place: one outside of the capitalist economy, free of the white gaze, racism, misogyny, classism and oppression. And that Edna Lewis achieved fame and fortune as people, with open arms, accepted and recognized that she was the Grande Dame of Southern cooking. None of these things are true.

I think the first thing that folks have got to understand is that Edna Lewis had a legacy, but only a very quiet one, until very recently.

DT: Would you characterize the recognition of her contributions to American cooking as coming at the end of her career, or would you post it to after her death? And I’ll qualify it as a recognition that isn’t equal to all her contributions to American cooking.

SF: Certainly recognition of her impact has grown exponentially since her death, but it did begin to come towards the end of her life. In her late years, she received honorary doctorates, and was often invited to cook and speak at food-related conferences and events. I will say that there were pockets of people who celebrated and revered her during her working life. But even now, most people—even in the food world—don’t know who she is. Or, if they do, they’ve only heard the myth.

DT: What was it about the turn of this past century that made it possible for her to start to get recognition?

SF: Food culture has evolved tremendously in the two decades of the 21st century.

A lot of the publications (newspapers and glossies) that used to act as gatekeepers of the food media have lost their monolithic sway with the rise of the internet, including digital publications and social media. I won’t go so far as to say food media has become democratized—that’s completely untrue—but there are a wider range of voices and perspectives being represented, and also a deeper appreciation of regional accents of cuisines both within and outside of the US. But even before that, circles of Southerners, food writers, and Black Americans were finding their way to Miss Lewis in the 70s and 80s. In New York, a group of Black chefs thought of her as part of the vanguard. They recognized that she paved the way for the specific articulations of American food coming out of their kitchens. Dr. Scott Alves Barton writes about this in his essay in the book.

DT: Can you talk more about Barton’s essay?

SF: Yes! Scott, himself, was a working Black chef in New York in the late 80s when he learned about Miss Lewis. His mentor, Chef Patrick Clark, brought Lewis to Barton’s consciousness. She was making a trip to New York, and Clark made it clear that it was a BIG DEAL, and emphasized that Miss Lewis had begun to make space for serious consideration and appreciation of Black American foodways. That she was a national cultural treasure, and deserved to be treated as such.

DT: So it was the concerted effort of black chefs and writers who lead the charge.

SF: Yes and no. Certainly, of late, I’d say Black food writers have been critical in articulating Miss Lewis’s importance: Toni Tipton Martin, of course, and also Michael Twitty. Both those writers have essays in the book. Toni Tipton Martin has been at this game for decades—she’s a true veteran food journalist—but her landmark work, The Jemima Code, didn’t come out until 2015. And Michael Twitty had a famously difficult time finding a publisher for his book The Cooking Gene, where he explores, in great detail, the diaspora of African peoples and their food culture. But also Francis Lam, who is Chinese American, has had a hand in amplifying Miss Lewis’s legacy. The vast majority of people who have been exposed to the work of Miss Lewis in recent years—and this includes plenty of working chefs and food writers—learned about her through Lam’s cover article in the NYT in 2015. He called me when he was beginning to research that piece to admit that he knew almost nothing about her. That story prefaces his article in Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original.

The myth is that Edna Lewis was a sweet, soft-spoken Black southern woman who was grateful for all the chances she was “given” after she left her hometown in Freetown, Virginia.

I would say the mid 20-teens is when things began to shift in the food media. Conversations around appropriation and authenticity in food were reaching a boiling point. Callout culture had begun to really take hold. So I think all of that converged in a way that led to a critical re-examination of Miss Lewis. Black chefs in major metropolitan areas were among those who were most aware of Lewis’s singular contribution to American culture and foodways. They also saw her within the context of Black erasure. And they spread the word. That said, those who brought Miss Lewis to (limited) prominence within the media were mostly white women: Judith Jones, Natalie Dupree, Alice Waters, Marion Cunningham. Jane Lear and Ruth Reichl, who were both at Gourmet at the time, are an important part of that story, too. In 2008, they posthumously published Lewis’s iconic essay “What is Southern?” in one of the magazine’s final issues, one built around that essay and celebrating the foodways of the American south. That’s where I first learned about Miss Lewis. That certainly tells you a bit about me and my own context as a Northeastern white woman borne to great privilege.

DT: Edna Lewis’s work spanned decades, but it took until the first decade of the new millennium for these white writers to cover her. What do you think was the impetus?

SF: I think Lewis shows Americans something about themselves that some of the broader American culture—even white culture, with all its blinkered ignorance and denial about the persistence and depth of racism—was beginning to hunger for. Her voice isn’t one among many—though there were certainly, as Toni Tipton Martin says in her essay, many Miss Lewises—because hardly anyone was giving those Black writers book deals, especially food book deals, until the 21st century.

DT: That is absolutely true. And from what we learned from #WhatPublishingPaidMe, there is a gross disparity between what White authors make and what Black authors make.

SF: Yes, the pay disparity is enormous. It wasn’t until this past year—2020—that finally there was enough public pressure on publishing to begin to pull down some of those walls. A lot of BIPOC writers have gotten book deals this past year, and a handful have been hired in executive roles at publishing houses. It’ll be very interesting to see how that plays out as those books begin to hit the market in the next couple of years. But it’s not just publishing. In Miss Lewis’s case, she had three major factors working against her: Her womanhood, her Blackness, and her subject (food). That third one is really important. Because people across the food world, with very few exceptions, are underpaid. Because in the US, we still don’t take food seriously as culture. Not the act of cooking (whether that’s in a restaurant or at home), not the practice of agriculture and food production, and not writing about food. We know this, and continue to ignore it. Lewis, unfortunately, is a prime example: posthumously, we celebrate her. But the stories that run about her leave out the painful parts, the tragic. parts, the enraging parts.

DT: Yes.

SF: Certainly not cookbooks, which a lot of publishers still think of as “lit lite” or women’s stuff. Food is sexy; it’s desirable, but it’s not valued, just like women, who have traditionally done the lion’s share of food work. Most women have, and still, perform and display their culinary skills and ingenuity at home, without attention or compensation. It’s considered drudgery, not artistic expression or talent. This remains invisible to a lot of folks because of that small group of mostly white men—successful restaurateurs, celebrity chefs with TV and book deals, or run food glossies—who make good salaries are those most visible in our culture.

DT: It is a ball of contradiction: everyone loves food, but turns away from the misery and injustice of workers all along the food chain. Actually, it’s not a contradiction: it’s how the system is set up.

SF: Exactly.

DT: I want to talk about Edna Lewis’s writing, especially the style and language she employed in her cookbooks.

SF: This is a fascinating thing to try to tackle, because she had four cookbooks, and each is completely distinct from the others. Three of the four were co-authored by white people (two by white women, one by a queer white man). And the other, The Taste of Country Cooking, though it wasn’t officially co-authored, was heavily filtered and edited by Judith Jones.

DT: I’d love to hear your breakdown.

SF: The first book, The Edna Lewis Cookbook (1972) was a reflection of Lewis’s catering career and life in New York City. It’s a global, cosmopolitan book where she helps herself to, and claims, the international pantry as her own. Caroline Randall Williams writes about this beautifully in her essay in the book. In Pursuit of Flavor (1988) was co-authored by Mary Goodbody, a white woman from the Northeast; she’d spend time with Miss Lewis in restaurant kitchens when Lewis was was pulling long hours as a working chef. It’s my least favorite of the books, yet it’s gotten a lot of attention lately because Knopf re-issued it in 2019. It’s a chef’s book with lots of tips and tricks that are certainly valuable in the kitchen, but it’s not a personal book; I feel Miss Lewis is muted in it.

I think Lewis shows Americans something about themselves that some of the broader American culture—even white culture, with all its blinkered ignorance and denial about the persistence and depth of racism—was beginning to hunger for.

Then, in 2003, The Gift of Southern Cooking, with Scott Peacock. This book is bathed in controversy that I don’t want to go too deep into, but suffice it to say there are many people who would prefer that Scott Peacock be wiped from conversations about Miss Lewis’s life and legacy. At the time, the two were living together and Peacock was helping care for Lewis. And both were in rough shape; Lewis, financially and health-wise, and Peacock, in a long battle with substance abuse. It’s an important book for American food, but I don’t think it’s true to Lewis. The archives show that he wrote most of it, even though much of the food is hers. And then there’s The Taste of Country Cooking, the book that most people know the most about.

DT: Let’s talk about TOCC.

SF: 1976, Knopf. Judith Jones. It’s an elegy to Freetown. A corrective Black history disguised as a cookbook. It’s an amazing book, a Trojan horse! And the writing is just gorgeous, as is the food.

DT: The writing is gorgeous.

SF: And, Edna Lewis didn’t finish high school.

DT: That, I did not know! I just assumed since she was a typist for the Communist Party…

SF: Nope, she began typing for the community party because of her ties to her husband, Steve Kingston, who was an organizer and agitator, not because of any qualifications. She was setting type, to be clear, not typing. She never learned to type. Her niece, Nina, typed up her manuscript for TOCC for her. She always wrote longhand on yellow legal pads. Those letters and manuscript snippets are incredible. Her eye for detail is on display everywhere. She had an incredible sensory capacity. But she did struggle with written language.

DT: The language of TTOCC is just beautiful.

SF: Yes, and the brilliance of TTOCC in terms of form is that it paired food—which everyone likes—with these truths that are both painful and went against the grain of popular narratives of American Black culture. Kind of slips them in under the radar, through this palatable medium.

DT: Her evocation of a particular occasion is everything.

SF: Yes, and occasions which were specific to the cycles of both subsistence agriculture and the natural world, and also specific to Black culture. Emancipation Day dinner, for example. Homecoming—an annual summer celebration tied to the Black church—is another. The deliberate omission of Thanksgiving, which her folk didn’t celebrate. But also meals that accompanied the cyclical life and labor of farming: meals for hog-killing time, meals for wheat threshing. The note about using springhouses to keep butter cool in the Virginia heat. And all of this food cooked on wood stoves! That Lewis was able to translate those recipes for folks cooking on gas or electric burners in late 20th-century home kitchens is really something. She famously asked her older sister, Ruth, to send her a parcel of ashes from the woodstove to evoke a smell of home when she was testing recipes for that book in her little sister, Naomi’s, South Bronx apartment. The authorities cut it open, thinking it was a drug stash. That, of course, is both hilarious and tragic: The invasive, ever-present suspicion of Black communication, Black commerce under the white gaze.

DT: This is the aspect that I like best of TTOCC, the specificity.

SF: Yes, Lewis understood what all great storytellers do: that the more specific you can be, the more universal your reach. She knew that instinctively.

Yes, and occasions which were specific to the cycles of both subsistence agriculture and the natural world, and also specific to Black culture.

DT: Was it only Judith jones who was unhappy with her first book’s co-writer, or was Edna Lewis also not feeling it?

SF: I don’t think it was so much that Judith was unhappy with her, it’s that she saw that Miss Lewis didn’t need her. The co-author was getting in the way of Miss Lewis’s own story and language, and that’s what Judith Jones was interested in; as an editor, that was her superpower, getting people to reveal their most intimate selves on the page. She was genuinely interested in other people, it wasn’t a put on. And that was apparent to Miss Lewis. Lewis’s story was also exotic to Judith Jones. They were contemporaries, but they were from opposite ends of the American experience in so many ways. And there were very, very few Black women being published in the 70s, pitifully few at places like Knopf; you know, the most esteemed literary houses. So there was plenty of tokenization going on, too. I don’t want to romanticize or gloss that. Natalie Dupree gets into that a bit in her interview in the book.

DT: Let’s talk about tokenization and romanticization. Edna Lewis has, rightly so, become an icon to the food world now. Her image was literally used on a stamp. That icon status, by its nature, flattens what is, in fact, a very dynamic life; for me, the lack of documentation of her time as a typesetter for the Communist Party is the best example. You have mentioned a few myths about her life, but what aspects of her life would you like more people to know about?

SF: I wish people understood that she was a radical in both senses of the word. On the one hand, she was pushing for things that went against the grain of her times. For example, her involvement with the communist party speaks, to me, not so much of her interest in or engagement with capital-P politics, but the values she was raised with, which were born of her ancestors’ experiences as enslaved and then newly emancipated people. They had tremendous capacity and skill—primarily agricultural and trade skills, and an incredible range of domestic arts—but very little money or material wealth. While I don’t think Miss Lewis relished her economic struggles, I don’t think she was particularly interested in the cash economy, and I think she had a deep—and inter-generational—distrust of capitalism. She understood exactly who it took advantage of, and how. That has major implications for, and applications to, today.

I wish people understood that she was a radical in both senses of the word.

And it’s been made all the more apparent in this past year we’ve just come through. She was also a vocal adopter of identity politics: as a woman, as a Black person, as a southerner. She was incredibly proud of who, and where, she was from, even when all of it made her less-than in the eyes of mainstream white American society and culture.

The way she presented herself was deeply influenced by her brief stint working as a docent at the American Museum of Natural History, where she got steeped in African diasporic history. And from then on, she wore clothes (that she made herself) that proudly advertised her ties to African cultures. But also radical in the other sense, radical meaning of the root, fundamental.

She was interested in a life that centered and attended to what’s essential, what’s fundamental to our existence as human beings: Food, mutuality, maintenance, care. She had a reverence for the natural world, and a deep devotion to responsible stewardship of land, that was way ahead of her time. When people talk about the environmental movement, they often think of Rachel Carson and her 1962 Silent Spring. Or, in the sustainable agriculture world, they talk about Wendell Berry—a white farmer and writer from Appalachian Kentucky—or Wes Jackson, another white agricultural activist of the same generation from Kansas. Lewis was saying a lot of the same things, just from a different angle. She, too, was calling for the same tender treatment of land in a way that, to me, echoes an indigenous perspective, one not grounded in private ownership and economic gain.

But publicly, her connection to those ideas and ideals weren’t brought to the fore. Instead, the back to the landers were in their camp (mostly white hippies who had gained from, and then rejected, the privilege of their parents), and then to the nascent farm-to-table movement who most people associate with Alice Waters. But Waters was learning from Lewis, and she (later) said as much. At first, Waters thought those ideas came from white Europeans. She had no idea there was as homegrown movement around ideas of sustainability and flavor in the US until she found Lewis. She—Waters—definitely didn’t do enough to turn the spotlight on Lewis, though, in a way I think is unforgivable, and also very typical, of white American culture.

DT: Yeah, it steams my partner, Tien, that people ignore that fact that Alice Water went to live poultry places in Chinatown for her ducks in the early days of Chez Panisse.

SF: Yes! And think about how much more interesting the narrative around Chez Panisse would be if Waters had been honest about all of that. It might actually have reflected American food and cooking in a much more accessible way. Instead, she rarefied and whitewashed it.

DT: BIPOC communities have been practicing sustainable agriculture long before hippies came.

SF: Yes, for millennia! All over the world. This is a central truth: if you don’t nourish and sustain the land, the land can’t nourish and sustain you. This, of course, is the kind of hubris, ignorance and short-memory that has led us right into our current moment, the collision of so many catastrophes: climate change, food and water shortages, wildfires, soil depletion, loss of biodiversity. And that’s before we get into details of the human and cultural toll.

DT: This is what I LOVE about Edna Lewis. Her writing is beautiful, but it doesn’t create a fence around her food.

SF: That’s so well put. No fence.

DT: I want to wrap this conversation up with a comment about the importance of cultural production.

specifically, the written word. Food is ephemeral and for Black cooks who didn’t have access to write their own books, their work is lost to us—or they’re stolen by white women employers. I’m grateful for all of Edna Lewis’s books; they’re evidence of not only wonderful cooking, but they also speak to a mind with an astute command of language that conjure up a time and place. And I’m thankful to all the contributors to Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original for adding to the written word about her.

SF: As am I. But, for me, they also elicit a longing for a whole world of voices—many, many generations—from whom, as you said, we’ll never hear. If there’s one thing I hope people take from Lewis’s legacy, it’s the vital importance of attending to and capturing culture and history as it’s unfolding in ways that support a less hierarchical approach to storytelling, that supports people speaking in their own voices, and from their own experiences. Without such heavy filtering and editing. Because, as the poet Elizabeth Alexander said, “Are we not of interest to each other?”

__________________________________

Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original, edited by Sara B. Franklin is available now via University of North Carolina Press.

Diep Tran

Diep Tran is the chef/owner of Good Girl Dinette in Los Angeles. She's an advocate for raising the wages of workers in the restaurant industry. Most recently, she was featured in the second season of Emmy award-winning series, "Migrant Kitchen."