Sally Franson on Fashion and Literature

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

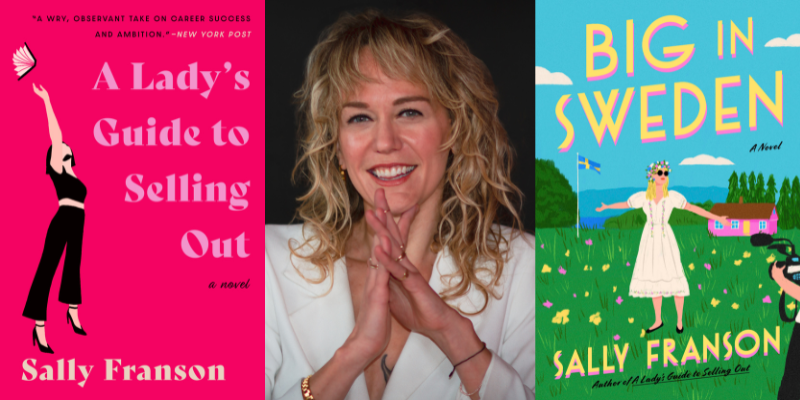

Novelist Sally Franson joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about Fashion Week 2024, the role fashion plays in characterization, and how stylish authors and characters have modeled and influenced tastes and trends. Franson reflects on her time working in the industry and discusses insiders’ perceptions of various Fashion Weeks around the globe. She discusses literary style icons including Isabel Archer, Nancy Mitford, James Baldwin, and Bridget Jones, and considers the influence of fashion in her first novel, A Lady’s Guide To Selling Out, which has just been reissued in paperback. She reads an excerpt from that book.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: The really interesting thing about some of the collections that were out this year is that some high profile designers used literature as an influence for their collections. Actually, it makes perfect sense to me, so I guess it’s not that surprising, and it’s one of the reasons that we’re doing the episode. This includes French designer Louis-Gabriel Nouchi’s Summer 2024 Collection based on Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man, and Anna Sui’s Fall 2024 seems like it’s linked to Agatha Christie. And of course, Joan Didion has become a writer and fashion icon.

Is literature often an inspiration for fashion, or vice versa? What kinds of conversation or brand signifying is going on here when these designers want to pick out these writers to refer to with their work?

Sally Franson: I think this is such an interesting question, and it’s one that I’ve been mulling over for at least a decade because we’re such an image-driven culture. We’re not a text-based culture, but people who are interested in literature are interested in the taste associated with literature. You can co-op images of authors and books, and then that becomes sort of a tribal affiliation or brand recognition.

Joan Didion became such an internet personality, you see her image all over Instagram—or at least I do. The picture of her in the car or smoking and looking out the window, one can attach that image of a writer to images of her books without ever actually encountering the books. I’m no Joan Didion fan. I’m sort of neutral on Joan Didion, which I feel like it’s kind of rare. It equally galls me, if I’m in a judgmental mode, or it just fascinates me, and I think the same could be true for James Baldwin.

James Baldwin is someone who had a really amazing style. I mean, that man could dress, and I think he took pride in it. He had what you can’t buy, right? He had taste, and he was doing interesting things with scarves and Polo shirts. He was wearing Izod, and he would buy them secondhand. If you Google, “James Baldwin Fashion,” there are people writing breathlessly about him in GQ.

I think for someone like James Baldwin, and Joan Didion too, the taste and style was an outcome of the mind. The mind was doing interesting things and had a rich interior. So, of course, that led to a rich exterior. In our culture now, we’re kind of like, “Oh, who cares about the interior, just look like Joan Didion.” And so, I think that fashion and literature have always been in conversation. There are so many books I can think of where characters are known via their clothes.

WT: I wanted to bring in this idea of literature or a writer’s work being captured by commercial culture and reprocessed as a brand. There’s a very interesting essay by Donald Barthelme called “On Not Knowing,” where he talks about the reason that he writes experimentally was to try to avoid that. He makes it really hard for anyone to take his work and make a fashion show based on it, because it’s too hard to understand.

SF: I think he succeeded at that.

WT: Yes, he’s done that. There’s no “Donald Barthelme” collections out, but he was very interested in the visual arts. He directed an art museum in Houston for a certain amount of time in his career. He cared about visual arts, but he didn’t want to be commercialized in that way.

SF: Right. The thing is, I don’t think that anyone who considers themselves an artist—or a lot of people—want to be commercialized. At the same time, we, the royal we, need cash flow. An example that comes to mind is that The New York Review of Books, I think last year, did a collaboration with the designer, Rachel Comey, where you could buy these maybe $500+ dresses that were printed with actual editions of The New York Review of Books.

In a way, I applaud The New York Review of Books. I feel like they probably have a relatively small audience, and they want that audience to grow. It has a good brand. It’s known. It’s known as “a place where intellectuals go to read.” But now, you don’t even have to read it. It’s too big. It’s unwieldy. You could just have a tote bag right with the cover or have a dress. That tension between art and commerce feels very fraught right now because of how the economics of American society is structured.

WT: I also feel that there are some artists who are more enthusiastic about commercializing their work than others. I feel like Ernest Hemingway would have been perfectly fine with an “Ernest Hemingway” collection of pants he used to wear. There is, in fact, a furniture line based on him, and he was fine with that. However, there are others who are not interested in that. Then there are people like Joan Didion or James Baldwin, who don’t have a say in it. Their image is being taken and their style, but they’re not around to manage it.

SF: It’s complicated for me, especially with someone like James Baldwin, whose work has meant a lot to me. I’m not trying to corner the market on loving James Baldwin at all, but he was such a radical person, and he seemed to be really living from the inside out. We would use the term “authenticity” when speaking about James Baldwin’s brand—which is totally disgusting to think about him as a brand, and it troubles me that humans are products now. It especially troubles me to think he lived his life working against dominant mainstream trends, and this one – the person becoming product – has swept him up. And Joan Didion, too.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: There’s this interesting line between when you’re presenting yourself to others… how are you caring about and perceiving yourself? And to what extent are you even willing to present yourself to others? I was just thinking, as you were talking about what it means to pay money for clothes, about fast fashion as a thing, particularly in the United States.

I love shopping with my mother, and we would go to stores, pick up shirts, and then we’d look at the labels and be like, “Odds on made in Sri Lanka?” The odds of being made in Sri Lanka are very, very high. It is cheap to make clothes overseas, and Americans are buying a lot of clothes. I have an absurd amount of clothes. This is also an environmental problem. If you clean out your closet to make room for the new season, what do you do with those clothes? At the same time, there’s now this profusion of clothes that are not made very well.

I’m working my way toward an analogy… We’re also at this moment in time when more books are being published than ever before. I would argue that a lot of those books are good, and there’s more space for good literature, but there is also this narrative of the market being flooded. “There’s so many things, there’s no gatekeeping, there’s too much stuff, it’s too accessible, anyone can write these days,” which is not true. This sense of abundance and cost that is causing us to value things in certain ways and perceive them as signifiers of taste or not. What do you think about my slightly messy analogy? Does it work?

SF: I think there’s definitely something to it. The proliferation of fast fashion has something to do with income inequality and something to do with rampant consumer culture. Also, our profound American belief in trash, right? If you buy something and don’t like it, throw it away. I feel like it’s the exterior that has meaning. So, if you can buy something cheap, but that’s trendy, or is going to have a tribal affiliation, it doesn’t matter if it’s going to fall apart in the wash, because you’ve got that hit of dopamine from belonging and having an exterior that lined up with the zeitgeist. That’s really troubling to me. If you do have clothes to get rid of, but you’re not able to give them away, H&M does do fabric recycling. Underwear, socks, things like that, they’ll make insulation and stuff from them.

About gatekeeping, I would say at least in publishing it feels like there’s a lot of gatekeeping. It’s hard to publish books, and it’s hard to write books. However, it does seem like “more is more” in terms of the acquisition, and I don’t know what to make of that. I don’t know what that means in terms of the value of an object. I was thinking about it because I just recently bought a brand new hardcover, and I thought, “Damn, this feels so good. I’m glad I paid 30 bucks for this.” When I was younger, I was buying Amazon paperbacks or used books, and I didn’t really care as much about how it felt or the physical experience of it. Now, I care a lot more, maybe because I’m getting older, and I’m more concerned with waste.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Mikayla Vo.

*

A Lady’s Guide To Selling Out • Big In Sweden (forthcoming) • “Shoe Obsession for the Ages: Prince’s Killer Collection of Custom Heels, Now on View” August 3, 2021 | The New York Times

Others:

“Top 10 best-dressed characters in fiction” by Amanda Craig, July 1, 2020 | The Guardian • “The Best Looks from New York Fashion Week Fall/Winter 2024” | Elle.com • “Off the page: fashion in literature” by Helen Gordon, September 18, 2009 | The Guardian • “Literature-inspired menswear collections for summer 2024” by Paschal Mourier| France24 • “Anna Sui’s new collection is inspired by Agatha Christie, so obviously the runway was at the Strand.” by Emily Temple | Literary Hub • James Baldwin • Joan Didion • Not-Knowing by Donald Barthelme • Rachel Comey and The New York Review of Books • The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford • Bridget Jones’s Diary by Helen Fielding • Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh •Little Women by Louisa May Alcott • The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James