Sad Books that Will Rip Your Soul to Pieces

Why We Love Reading To Cry

I learned my lesson with Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. A few days before having surgery that would render him immobile for weeks, my father requested that I lend him some books to read. I carefully selected a stack of new releases and a few classics he had never gotten around to.

After the surgery, I got a call from my mother letting me know everything went well, but my father forgot his overnight bag—would I mind dropping it off?

I did, and my heart sunk as I saw my father hooked up to a series of wires, taped up around his arms and stomach. It sank even deeper when he opened his duffle bag and sitting right at the top was The Things They Carried.

Of all the titles I gave him—Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding, Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve, Brenda Wineapple’s Ecstatic Nation—Tim O’Brien had been tossed in as an afterthought. We’d chatted about war literature over lunch the other day and I commented that the book was favorite of mine. He said he would like to read it sometime. Little did I know that he not only wanted to read it, but that he would also bring it with him directly after having had invasive surgery.

After the mishap, my book recommendations come with something akin to a surgeon’s warning: Do not operate heavy machinery within 24 hours of reading this book. Stop reading if experiencing symptoms of existential turmoil, sadness, etc. May cause dizziness, anxiety, angst, questioning of one’s life choices.

Despite my spotty history of book recommendations, I work in a bookstore now. The other day a woman walked up to the counter holding a copy of Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air. “Will this make me cry?” she asked me. I told her: yes, it will. I insisted she buy it anyways.

Only three books have made me full-blown ugly cry: The Selected Stories of Alice Munro (“The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” if we’re being specific), Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, and the fifth Harry Potter book.

There are some books that become renowned largely for their capacity to make people cry— just look at Jodi Picoult’s entire career. People enjoy going into a sad book like it’s some kind of a mountain to be climbed. We crave the emotional labor that comes with reading a book that is particularly difficult or sad. But what I also notice is the sense of camaraderie between readers that comes with a particularly trying text.

In Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (surgeon’s warning: take with a glass of whiskey late at night, read in one sitting), she considers our need for shared sadness: “…we sometimes weep in front of a mirror not to inflame self-pity, but because we want to feel witnessed in our despair.” Why bother with the mirror when you can pick up a copy of Anna Karenina?

I worry that we don’t let ourselves express sadness as often as we ought to. And I don’t mean my-grandma-just-died-and-I’m-inconsolable-sadness or my-boyfriend-of-three-years-left-me-and-he’s-taking-the-dog-sadness. Don’t get me wrong, those are very valid types of sadness, but what I’m interested in is boring, monotonous sadness. We tend to reject sadness that doesn’t have some tangible cause. We are not offered many opportunities to feel communally sad for no reason whatsoever.

There’s something so necessary about picking up an author like Alice Munro, whose stories are equal parts beautiful and devastating, and realizing that someone sees the sorrow in everyday occurrences. I cry when I read Alice Munro and I don’t even cry at the sad parts. I cry when a character gets too drunk at a party because she doesn’t know anybody and makes a fool of herself. I cry when a woman tries on a dress at a boutique and feels bad for wanting something nice for herself. I cry because these moments seem so trivial in isolation but so meaningful in Munro’s capable hands. In my own life, I don’t cry when I want a pretty dress (mostly): I tell myself I’m being ridiculous and carry on. Authors like Alice Munro allow us to embrace these moments of weariness, tell us we’re not alone, let us feel sad.

* * * *

Of course, there’s a fine line between a book that will make you cry and a book that will rip your soul to pieces. I recently chatted with a customer purchasing a copy of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. She told me that she and a friend gave each other a copy for Christmas and have been reading it together. She regretted that she was a bit ahead of her friend. She wanted to tell her friend that things get better for the characters, but she simply couldn’t give her that false hope.

When I asked who the third copy was for, she responded: “Oh, another friend—we’re thinking about starting a support group.”

Over at The Millions, poet Saeed Jones echoed this sentiment: “There should be a recovery group, ALL-Anonymous, for people who, like me, didn’t know that a book could be so gorgeously wrought and exacting at the same time. That book hurt me; I’m not sure if this is a recommendation or confession.”

While there’s only a small handful of books that have made me cry, the list of books that have hurt me is nothing if not extensive. I could structure a half-way decent English 101 course around books that have triggered my panic attacks: The Bell Jar, American Pastoral, Hamlet, The Sound and the Fury, Hamlet again, The Sorrow of War, The Corrections. It seems I have a unique tendency to forget that I am not, in fact, fighting in the Vietnam War, nor am I a doomed Danish Prince, and I am certainly not a former high school sports superstar going through a life crisis.

Often customers in the bookstore ask me what I’m reading and my first impulse is to apologize to them, “Everything I’ve read lately has been so depressing!” I always have a list of back-up books in my head that I can give people instead.

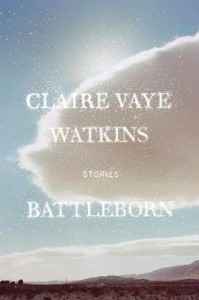

There’s a list of books that I love, but cannot bring myself to spring on random strangers. They’re books I adore deeply, have changed my life and cut to my core, but, so help me, they are bleak. They hurt. The first time I came across Claire Vaye Watkins’s stunning story collection Battleborn, I had to pause every few paragraphs to collect myself. Her stories, most of which are set in the deserts of Nevada, stood out with such sharp, precise clarity that everything else I had read before and after that felt like a fuzzy dream. The short stories of Joy Williams have had a similar effect on me—surgeon’s warning: be prepared for sudden onsets of intense emotional pain. Read her story “Taking Care,” which skulks along snowy New England so beautifully that you hardly notice the despair lurking under the ice, and you’ll see what I’m talking about.

We want to feel sadness; we want to protect others from sadness, both theirs and our own. I don’t want to be held responsible for handing someone three hundred some-odd pages of sadness and pain. It broke my heart when I saw my father bandaged up and trudging through Tim O’Brien—to this day, he still shows a bit of apprehension when I hand him a book. I can warn readers all I want, and in the event that I do sell you a bundle of sadness: you’ll know where to find me if you need to cry.

Lindsay Lynch

Lindsay Lynch is a writer and a bookseller at Parnassus in Nashville.