In the subway, Petrarch and I see a strange thing: a trio of blind men, arms linked, lurching along like the cars of an inebriated train, with a subway worker shepherding them down the platform to the exit.

Once they’ve gone, Petrarch tells me one of his stories.

It took place in Mexico City in 1998. That was the year he finally graduated from high school. The twenty-one-year-old high school grad: his problem-child badge of honor. And a nod to the anachronism that had always been part of his fate. Like having a first name straight out of the late Middle Ages, for example. Like his hair turning white when he was still a kid.

The youngest of nine siblings, his birth was both the culmination of ancestral mistakes and the promise of a change. His mother was forty-six, but no amount of medical warnings could overcome her desire to have a poet named Petrarch for a son. And so she offered him the chance to know her in the way that only he ever would, as well as bestowing upon him the gift of losing her (“massive coronary thrombosis”) when he was only eleven.

When he decided to go to Mexico, Petrarch had been rock climbing and mountaineering for five years. Mexico City and its foothills were the ideal place if you wanted to pursue either of these in a serious way. Martín, his older brother, said he really ought to study or get some sort of job as well. Petrarch remembered that Achilles, a friend from high school (one of several he’d passed through in his teenage years), lived there and might be able to help. And that was what happened. No sooner had he arrived than he was taken on as an intern at the TV station where Achilles worked doing the sound design on Mexican soap operas.

“A soap opera is its sound and its voices,” Petrarch says. “Nobody really watches soap operas. They listen to them while they’re doing the dishes, washing their clothes, reading the paper.”

Voices, I think. Petrarch telling me about his mother’s voice when she read him the Canzoniere at age eight. That was also when he told me about his time living in Capaya, a small village in Barlovento where his father had a finca. He came away from there with a liking for poetry, for the connection between philosophy and nature, and with a passion for knives. It was from his father—who was unmistakably a Trujillo State man (he sometimes threatened to slit his son’s “little pot,” meaning slit his throat)—that he got both his recalcitrance and his fondness for settling an argument with recourse to a blade.

“As well as a poet, my mom wanted me to be a shepherd. So she bought me a goat to graze around the village. But Capaya was a wasteland, the only place any grass grew was the cemetery. My mother and I would go there together, wearing our robes with plaited belts, the goat in tow. And at the cemetery she read me Petrarch’s Canzoniere.”

When he came back from Mexico, he ran into Yana, his best friend from childhood, in the Central University Philosophy Department. Petrarch had given up rock climbing and Yana had given up on a marriage. The romance that followed was like Being and Nothingness in a romantic key.

But before the study of philosophy came philosophy in practice.

“Mountaineers and rock climbers are philosophers,” Petrarch says. “They both think about things in abstract terms. Climbing Everest or drinking thirty beers in a night, it’s all the same. The next day they smoke a joint and forget all about the absolute and their hangover.”

Petrarch had initially started climbing rock faces as a literal way of avoiding getting dragged under. He was sixteen. His mother had died five years earlier, his father had gone back to Trujillo in a fugue of alcohol, and now brother Martín and his wife Jimena, who until then had been his de facto parents, were leaving for New York.

He was supposed to stay in Caracas with some of his other siblings, but it felt to him like he was falling behind in the race of life, languishing in that last spot which is solitude at its most absolute.

“Around the time when Martín and Jimena left,” Petrarch says, “everything very nearly went to shit for me.”

To avoid coming last, he decided to completely alter the coordinates. To switch the horizontality of x for the verticality of y. He dropped out of school and started scaling mountains and cliffs.

I know nothing about what he got up to between ages sixteen and twenty-one. Between the decisions to climb and to climb even higher still. Desperation can be a deep pit, but it can also be a mountain peak. Let’s put Petrarch equidistant between the two kinds, weighing them up like cards obscurely encoding his whole future.

Let’s imagine this, and then skip forward a little, to the end of 1998 in Mexico City. In the environs of Zócalo, with Petrarch trying to locate an address.

“La Ópera, you say?” said the taxi driver who had brought him downtown. “Kinda like the theater, isn’t that?”

“La Ópera Bar,” said Petrarch. “No idea. I’m from Toluca.”

Petrarch paid the fare and set out walking. He asked an old man who, after scratching his head, confessed that he was from Querétaro.

“I’ll take you there, young man,” said a voice.

“A very sonorous male voice,” Petrarch says. “A voice like that of an actor out of a soap opera.”

Which made it a surprise to turn around and find what he found. He hesitated, but the blindman’s raised arm, which it clearly took some effort for him to hold aloft, forced Petrarch to decide quickly.

And so, together with his guide the blindman, he headed in the direction of La Ópera.

La Ópera is like a saloon in a Western. Saloon doors, bar constructed from wood, wooden ceilings, wooden floor. A lot of wood.

Once the two of them had taken a table, the blindman sat with his eyes turned to the floor. After a few seconds, he lifted his milky-eyed gaze and scanned about in the soupy air, before calling to the bar owner.

“How’s it going, Miguelito? The young man here wants to see the bullet holes.”

“Of course,” said Miguelito, pointing up towards the darkness of the ceiling. “What can I get you both?”

“I was floored,” Petrarch says.

Apparently, when he’d heard Petrarch on the street, the blindman had recognized his accent and, being Venezuelan himself, decided to help. But when he spoke to the bar owner, his accent sounded Mexican.

“Two Modelo Negras for us, Miguelito.”

“And I have no idea how he knew I’d gone there to see the bullet holes that Pancho Villa was supposed to have left in the ceiling,” Petrarch says.

“What? You’re surprised?” the blindman said. “All the tourists come for the same thing. And they’re all equally disappointed when they get to see it.”

“And what’s your name?”

On the way there, Petrarch had introduced himself, but the blindman was still yet to.

“Tiresias,” he said. “Seriously?”

“No. I’m messing with you. I’m called Juan.”

Although he wasn’t called Tiresias, the blindman seemed to know everything about him and about Francesco Petrarch. In the course of the magisterial lesson on lyric poetry that followed, with all the skill of a pickpocket, the blindman recounted the story of his life. All without Petrarch even noticing he’d stolen his wallet.

“Forget about Diana,” he said, when the lecture was over. “Yana, with a y,” said Petrarch, interrupting. He drew a

sloped incline in the air with his finger, a mountain in profile, as though the blindman could see it.

“Ah yes, Yana—forget about her. If she’s already married, you should let her be dead to you. You should take the permanent position they’re offering you at the TV station, so you can go on with your rock climbing and all that stuff. And your writing. That’s the only way you’re going to do as your mother wished and become a poet.”

You should, you should, Petrarch repeated to himself.

Was that conversation really happening? Could it be true that his Tiresias went by the name of Juan and lived in Mexico City? Was he also destined to become a Venezuelan lost in Mexico? Wasn’t the very fact of putting these questions to himself like this, in a TV-like voiceover, already a sign?

“The real Petrarch took up mountaineering during his exile in Vaucluse,” said the blindman. “That was where, in 1337, ten years after the April 6 when he had first laid eyes on Laura as she came out of the Church of St. Claire in Avignon, he started work on his eclogues and the Canzoniere. He wrote a good number of the former, and almost the entirety of the latter, while he was there.”

“April 6?” Petrarch asked. “1327,” the blindman confirmed. “April 6.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And he was a mountaineer.” “Yes.”

“And who’s this Laura?”

“The love of his life. I won’t say it was an impossible love, because true love is always impossible. The poet’s task is to find love, in order to lose it later on and find it again in poetry.”

__________________________________

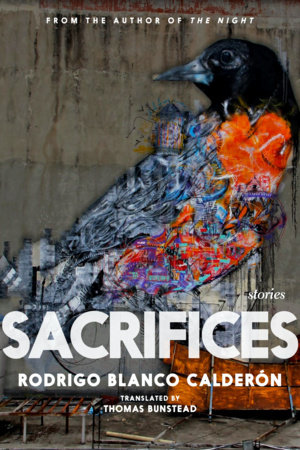

From Sacrifices by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón (translated by Thomas Bunstead). Used with permission of the publisher, Seven Stories Press. Copyright 2022 by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón.