Ruthie Fear felt the nearness of unseen beings. On fall trips into the national forest to poach firewood with her father, she searched for them in the bushes between the trees. Patches of larch flamed ocher in the midst of the evergreen forest. The smell of butterscotch wafted from ponderosa bark. Ruthie walked carefully, avoiding fallen branches. Like the winged skeleton, the beings seemed to follow her; only their shadows remained by the time she whirled around.

“All this land used to be free,” her father said, stopping to appraise the trunks surrounding a small clearing. “Free game, free wood.” He’d been a stacker at the mill and now worked whatever construction jobs he could find. He tapped the head of his ax against a young ponderosa, and nodded at the dull tock. He stepped back. “Now the government thinks they get to decide who uses it.” Ruthie watched him brace his feet and shake loose his shoulders. The tree he’d chosen was twice his height, with a straight, reddish trunk and thin branches growing thinner to the needles at its top. The ax’s haft doubled the length of his arm. The blade’s concave head gleamed. A maul. Ruthie couldn’t remember where she’d heard that name, but it seemed fitting. What her father was about to do to the tree was what a bear would to him.

Blisters from previous firewood expeditions marked the palms of his hands. It was their first season harvesting their own wood. They hadn’t needed to when he worked at the mill. His eyes fixed on a single point on the bark. “The woods will only be for the rich.” He raised the ax and swung it down in a hard, smooth, clean motion. The wedged blade chunked into the wood and he immediately jerked it back, in rhythm, to chunk again. “With them shutting down the mills and the mines.” His muscles strained with each successive chop. The wedge deepened; veins stood out on his arms, his body like the piston of some terrible machine. Splinters shot from the trunk and littered the ground around him. He began to sweat. “All these towns are going to die.” The violence of the work increased, as if he and the tree were pitted against one another—both could not remain standing. The blisters split open on his palms. The tree began to moan. Ruthie covered her ears. Sap leaked from the scaly bark, like the blood on her father’s hands. When the wedge was deep enough, Rutherford circled the trunk, wiped his brow on the shoulder of his T-shirt, spat, and began on the other side. Ruthie watched him, torn between fear and love. His swings slowed, hacking unevenly into the new wedge to create a hinge with the other, but still they did not cease. The treetop swung unsteadily in the breeze coming down from the mountains. It leaned over him.

Ruthie backed to the edge of the clearing. Would this be what killed him? It seemed fitting: a tree he’d cut falling down on top of him. She touched the bark of another ponderosa and felt its rough, steady life. The butterscotch scent had grown stronger, marred now by suffering.

Ruthie, Rutherford, and the dog Moses lived at the mouth of No-Medicine Canyon near the southern end of the Bitterroot Valley.The tree fell with a rending creak. Her father hopped to the side as branches popped overhead. It crashed down beside him and for a moment he was lost in the dust that billowed up from the ground. When the trunk settled, neatly bisecting the clearing, he stood over it. Sweat ran down his dirty cheeks into his beard. Broken branches hung like garlands from the pines around him. Sunlight poured through the fresh space above the stump. Rutherford looked at his bleeding palms. He grimaced. “They always put up a fight.”

On the long walk home, Rutherford knelt beside Trapper Creek. The large bundle of wood on his back loomed over him as he rinsed his palms in the water. Ruthie—her own, smaller bundle chafing her shoulders—watched the blood slip away in the current: two red, ropy fish elongating as they were carried downstream.

Ruthie, Rutherford, and the dog Moses lived at the mouth of No-Medicine Canyon near the southern end of the Bitterroot Valley. Above them, Highway 93 rose to the hot springs and Lost Trail Pass into Idaho. Their teal trailer was set across the driveway in front of a single acre of barren ground eight miles from Darby, Montana. Theirs was the smallest property on Red Sun Road. In the winter, they slept side by side next to the woodstove, the windows sealed with plastic to hold in the heat, a towel stuffed in the crack beneath the door. The sheet metal siding rattled in the wind. Ruthie was often too cold, or hungry. The Bitterroot Range loomed overhead. Ten-thousand-foot peaks seeming to attack the sky with jagged, glaciated teeth. These were mountains that forced Lewis and Clark a hundred miles north and ended, once and for all, their dream of a northwest passage.

The north entrance to the valley was marked by a sign reading jesus christ is lord of this valley, and the south entrance by a sign advertising Second Nature Taxidermy School, where farm boys with ghoulish ambitions came to learn the modern, fetishized art of embalming. Between these risen corpses, thirty thousand people lived.

When Ruthie pressed her face against the window of her closet-sized room, she could see Trapper Peak, the tallest in the Bitterroots, hooked like a finger beckoning her above the tree line. Circled by bald eagles and white with snow eleven months of the year, it reassured her that men were small scrabbling things, crawling across the ice unaware of the depths below. The boys in her class made each other bleed with straightened paper clips. Her father’s friends—Kent Willis, Raymond Pompey, and the Salish brothers Terry and Billy French—drank themselves into stupors of displaced rage and stumbled outside to shoot bottles off a busted washing machine. The glass shards glinted kaleidoscopically in the morning sunlight while the men snored in the living room, their arms sprawled tenderly over each other’s chests, showing affection in sleep in a way that would be impossible awake. Tiptoeing around them to the bathroom, Ruthie wanted to fly away. She climbed on top of the toilet and wedged her head through the small window. Her gray eyes had a yellow ring in the irises like the beginning of an explosion, noticed by strangers, that she hoped would allow her to see farther. She tasted a storm approaching in the air. Saw herself zooming over the spent shotgun shells, the glittering pattern of glass, the cannibalized dump truck her father used as a kind of fort—full of discarded whiskey pints and Bowhunter magazines—to perch atop Trapper Peak and look back down on her life, free from its bonds and humiliations.

Sleep crust stuck in the corners of his eyes. A red rubber band loosely held his ponytail. He smiled down at her.When the storm came, she ran outside to catch frogs in the rain.

As if in opposition to the mighty peak, No-Medicine Canyon was a dark, narrow portal where wind sprang up of its own accord, to scream and rage and then cease without ever leaving the canyon’s confines. Ruthie feared it instinctively, as did her father. They never went inside. She was sure that twenty thousand years of spirits lived within, beginning with the People of the Flood, a tribe whose marks were washed away when the ice dam broke at Glacial Lake Missoula fifteen thousand years before, but who remained below the dirt. Her friend Pip Pascal had found one of their fertility icons on the bank of Lost Horse Creek. A plump, headless stone figure of mounded breasts and pubis that caused both girls to look down over their own skinny bodies and think, No, this could never happen to us. They found other mysteries along game trails: strange dragging tracks, ancient flint tools, figures with many arms chipped into the west faces of boulders.

“You should be afraid of every canyon,” Terry French told her, when she asked. He and his brother were the only Indians Ruthie knew, and she came to them with her most pressing concerns. He smiled and palmed her head. His wide, scarred fingers easily curled over her skull to the nape of her neck. “You’re six years old and you weigh forty pounds.”

Ruthie stared up at him around his thick wrist. Sleep crust stuck in the corners of his eyes. A red rubber band loosely held his ponytail. He smiled down at her. “Now help me get this meat into your freezer so you and your dad don’t starve.” The butchered hindquarters of an elk, poorly shrink-wrapped, dripped blood in the bed of his truck. He handed Ruthie a package of steaks. Reluctantly, she lugged it inside, dumped it on the kitchen table, and left Terry in the kitchen talking to her father about where work might be.

She watched the canyon. There was something inside, she could feel it. Water slid down the cliff walls, slicking the granite black as obsidian. Strange ferns and mosses grew along the bottom of what was once a mighty riverbed and now held the low flow of Trapper Creek. Ruthie walked to the edge of her yard and pissed in the soft dirt. She saw the chasm that formed, the power of water. The ferns trembled in the wind. The long shadows held a wet, fecund darkness utterly apart from the dry valley outside. Ruthie shivered and pulled up her pants. She walked as close to the canyon’s mouth as she dared. Moses barked and ran across the yard to her side. She touched his ears. He sniffed the air, worried. Bleached skulls were piled in the far corner by the shed. Hunters from all across the valley brought trophy heads to be cleaned by Rutherford’s dermestid beetle colony inside the shed. It was his only regular source of income since the mill closed. The fifty thousand beetles lived among wood shavings in three large plastic bins beneath heat lamps. In a constant state of voracious hunger, they could remove every shred of flesh from a bear skull in twenty-four hours, leaving the bone porcelain-clean and preserving all the delicate structures within the nasal cavity. Ruthie sometimes snuck in to watch, transfixed, as the beetles swarmed over the flesh, flooding the orifices, adults and larvae working together with a speed that filled her with dread. On the coldest nights of winter, when the heat lamps weren’t enough, Rutherford brought the bins into the trailer and Ruthie had to listen to the larvae squirming over one another as she tried to sleep on the wolfskin rug.

Ruthie smelled something from the canyon’s depths: a rot, a dead thing come back to life.She knew not every girl lived like this. Some had mothers who sang lullabies.

Moses began to tremble. What was in there? Ruthie smelled something from the canyon’s depths: a rot, a dead thing come back to life. She crouched beside Moses and rested her hand on the wiry fur of his neck to calm him. He was a Yorkie, always alert, save for in midwinter when he grew depressed. His breath came in quick pants. Together they stared into the shadows.

She probed the darkness. Green blades of grass, tall in the spring, wavered in front of her eyes, dividing her vision by oscillating degrees. Straining to see farther, using the yellow in her irises, she channeled her entire being into the canyon. The sounds of the outside world ceased. The sun was swallowed by blackness. She felt herself standing on the edge of a giant open maw—an abyss of incomprehensible depths into which all previous explorers had fallen. Moses’s body shook as if he felt it, too. Only the dark of the canyon remained.

A shadow slid over another shadow. Ruthie froze. She gripped Moses. Something was moving.

The creature took shape slowly, awkwardly. A tall feathered thing, it lurched toward the creek on two long, spindly, double-jointed legs. Each step was tentative, as if it were just learning to walk. Its feathers were gray and slightly iridescent. Its body curved into a single, organ-like shape. A kidney. Misshapen and lumpy, frighteningly perched atop the thin legs—taller than the saplings on the shore. A monster, deviant in its unsteadiness. But what horrified Ruthie, what made her want to scream, was that it had no head.

Ruthie felt like she was caught in a dream, unable to run, seeing a future of death.Its chest continued roundly over its collar and back along the ridge of its spine. Nothing protruded. No way to see nor hear nor smell, no orifices at all. Yet it paused by the creek and leaned forward as if it wanted to drink.

Ruthie felt like she was caught in a dream, unable to run, seeing a future of death. She wondered how the creature had grown. She imagined it wriggling, maggot-like, from the mouth of a dying elk, before growing to its terrible size. It reminded her of the tumor-ridden lamb that Len Law had shown off in front of her school, or the mold that grew around the drain of her shower.

Moses began to growl deep in his throat. His wiry hackles rose. The creature lifted one of its pronged feet and dipped it into the water. It stood like this helplessly. The current rushed around its thin ankle. Ruthie was sure it would be knocked over. She didn’t see how it could get up again. Sudden pity mixed with the fear and revulsion in her chest.

The growl in Moses’s throat crescendoed to a harsh, hysteric yap.

“No!” Ruthie hissed.

The creature twisted toward them. It faced Ruthie with its feathered mask. The feathers trembled. Sensing her. Knowing she was there. She wondered if it navigated through vibration, like a bat. She could feel trucks on the highway when she pressed her ear against the dirt. The creature shied backward, stumbled, straightened on its stilt-like legs, and shuddered away into the darkness.

The canyon was empty again. Ruthie parted her lips. No sound came out. Cold sweat ran down her neck. She felt a terrible importance, as if fate were for a moment balanced in her hands. Hers and her father’s and that of all the others in the valley. Moses looked up at her with the whites of his eyes showing, frightened and begging for a treat, the way he did when a truck horn scared him in the night.

__________________________________

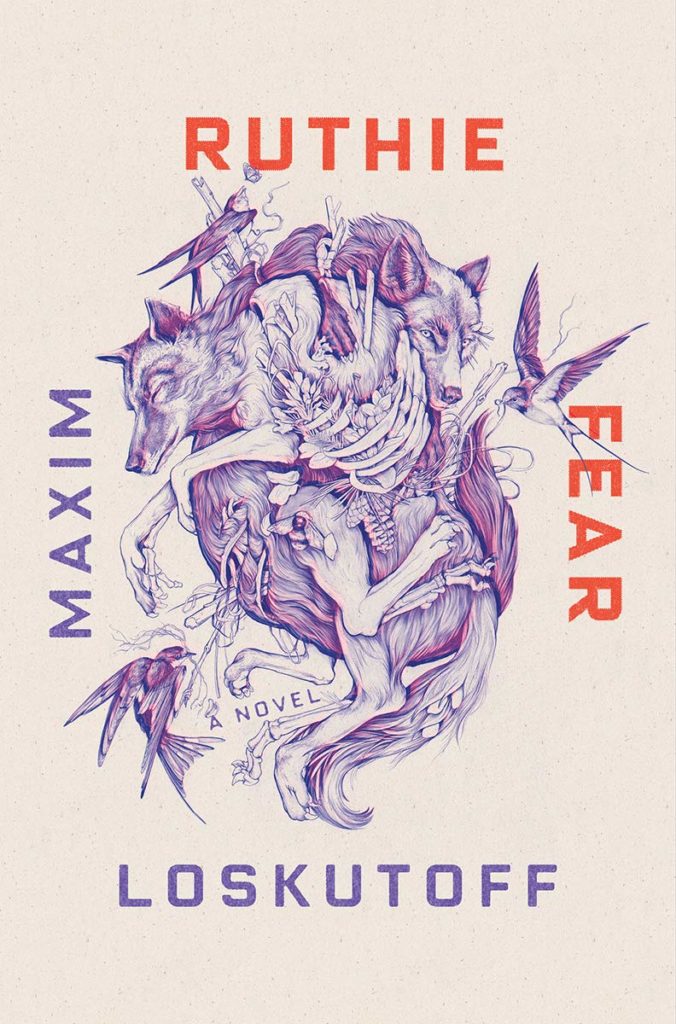

Excerpted from Ruthie Fear by Maxim Loskutoff. Excerpted with the permission of W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2020 by Maxim Loskutoff.