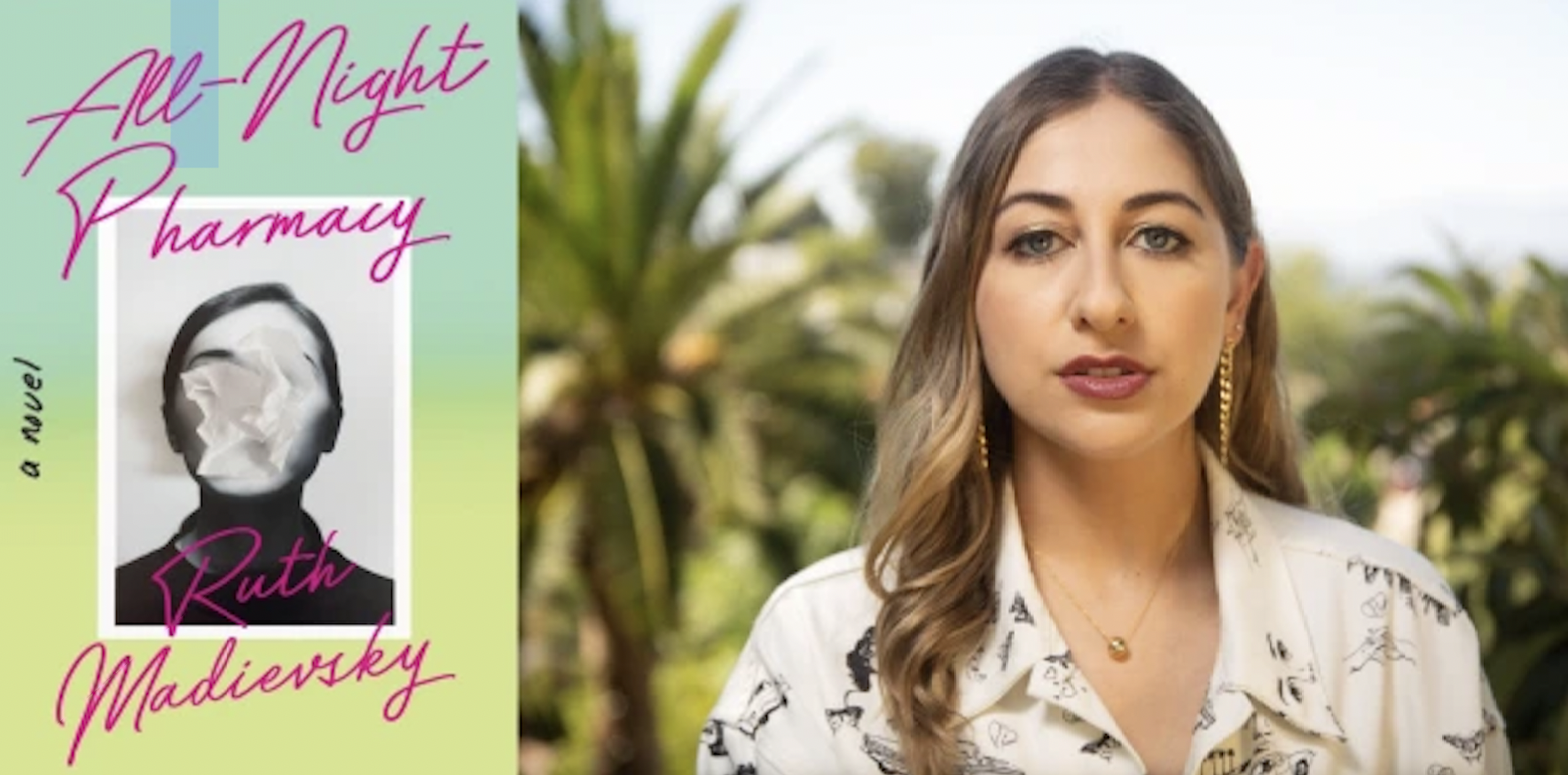

Ruth Madievsky on Creating Fiction From Poetry

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of All-Night Pharmacy

Ruth Madievsky’s first novel begins as a tightrope walk across a neon-lit LA, with an unnamed teenage narrator in thrall to her older sister Debbie, struggling to unbind from her psychotic mother, living in a desultory relationship with a man who pays the rent, hanging out at a dive bar where she day drinks and experiments with the drug of the day. After a violent break from Debbie, she tries rehab, finds work in an ER, falls in love with a psychic woman, who travels with her to their homeland of Moldova, and begins to see a future unspool.

The narrative voice—raw, outrageous, iconoclastic, often hilarious—spins this novel into place, transforming the harsh realities of the narrator’s troubles into a sort of radiance, making All-Night Pharmacy a memorable debut. In our conversation, I learned about the author’s influences and how this novel emerged after years of hard work and a hectic multitasking life.

“I was working as a clinical pharmacist at a hospital in Boston when the pandemic hit, taking care of patients with cancer and with HIV,” she told me. “Sometimes I also covered whichever unit had been designated the COVID-19 floor. It was a wild time; our COVID-19 treatments were changing constantly, and I was learning something new every day. It was terrifying and deeply rewarding. My agent [Mina Hamedi at Janklow and Nesbit] offered to represent me in March 2020, the week that everything shut down. What a hopeful thing in such a chaotic time: two strangers agreeing to make art together.”

She moved back to Los Angeles and started working outpatient as a primary care and HIV pharmacist. “We went on submission with All-Night Pharmacy while I was training at the new job, which turned out to be a great distraction from checking my email every two minutes. Between 2020 and now, I also got married and had a baby. Giving birth three months before your debut novel publishes… extremely chaotic! I’m bringing my baby on tour and look forward to leaking milk across America’s indie bookstores.” Our conversation by email was based on the West Coast.

*

Jane Ciabattari: What inspired All-Night Pharmacy, your first novel, which revolves around two sisters in a destructive relationship? (As you put it in your opening line from your eighteen-year-old narrator, “Spending time with my sister, Debbie, was like buying acid off a guy you met on the bus.”)

Ruth Madievsky: Neon signs, Los Angeles dirtbaggery, the opioid epidemic, intergenerational trauma, toxic Russian talk shows, the legacy of the Holocaust, absurd family stories in the face of a destroyed archive, fraught sisterhood, addiction and recovery, urban loneliness and gentrification, who has the privilege of being a mess and who doesn’t, queer-coming-of-age, and Jewish mysticism.

JC: How did the novel evolve, adapted from short stories? (And how did T.C. Boyle, who you studied with at USC. influence those early stories?)

RM: I never thought I could pull off writing a novel. Sixty- to one-hundred-thousand words in service of a cohesive plot? Hard pass. While I was in pharmacy school, T.C. Boyle would come to USC’s campus once a semester to meet with Creative Writing Ph.D. students by appointment. I was very much not in the Ph.D. program…my classes were on another campus entirely. But I attended the program’s readings so often that I think the administration assumed I was involved? Or they could smell the desperate stench of FOMO on me and threw me a bone?

Either way, I met with T.C. Boyle several times, and he was the first person to see the linked stories that became All-Night Pharmacy. He has a light touch when it comes to feedback. Mostly we talked about what my stories were doing, and he encouraged me to find an agent and keep going. That was 2014-2016, I believe. I pretty much only wrote new stories in the All-Night Pharmacy universe when T.C. Boyle came to town.

In 2019, a literary agent reached out after reading some of those published stories online. I called my manuscript a novel-in-stories to make it sound more commercial (they’ll never see through that one!). Five years of work had amounted to forty-eight double-spaced pages. The agent, who I ultimately didn’t end up signing with, suggested I rework the book as a novel using some of the themes that linked the stories together as narrative throughlines.

I didn’t have a lot of faith in my ability to pull it off, but I decided to try. I forced myself to write 500 words a day for a month, which I emailed to my writer friend, Billy O’Neill. Exchanging pages every day was the only way I could get out of my own head, and it’s how the first draft got written.

JC: Did your writing of poetry help shape this novel?

RM: Definitely. It was mostly a blessing, and occasionally a curse. I bled over every word. Early drafts paid too much attention to the language and not enough to the plot and characters. Why make difficult craft decisions when you could string a bunch of mic drop moments together instead? With a poem, anything—narrative, structure, mood—can be abandoned in pursuit of beauty. That’s how I was used to writing. Revising the novel involved cutting a ton of lines that were basically a flex and weren’t serving the book. I actually have a Craft of Writing essay coming out in Lit Hub that elegizes my departed bangers. Every word that made its way into the final draft fought tooth and nail to be there.

JC: Which writers were you reading while working on All-Night Pharmacy?

RM: *Takes a deep breath* Jean Kyoung Frazier, Jean Chen Ho, Kyle Lucia Wu, Kimberly King Parsons, Kristen Arnett, Melissa Broder, Raven Leilani, Bryan Washington, Alexander Chee, Garth Greenwell, Ilya Kaminsky, Brandon Taylor, Natalie Diaz, Andre Aciman, Rufi Thorpe, Mary Gaitskill, Denis Johnson, Torrey Peters, Mohsin Hamid, and Miriam Toews—to name a few!

JC: The narrator’s mother’s “kaleidoscope of diagnoses” possibly include major depression with psychosis, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Her grandmother is a “hard woman” who immigrated from Saint Petersburg in her twenties, after her father was murdered as an enemy of the state. Her great-uncles, great-aunts and cousins had perished in Nazi death camps decades earlier. How is the narrator shaped by this family history?

RM: I was interested in the ways that historical trauma manifests in those who are generations removed. Our narrator’s mother, who was born in America, is deeply paranoid that her family’s experiences under Soviet terror will be repeated. The narrator hasn’t had her life threatened by the state, but she gets into perilous situations constantly. She knows her relationship with her sister is toxic, but she’s unwilling or unable to cut ties. She’s haunted by an emergency room patient complaining of Shoah grief and gets drawn into a psychosexual relationship with an alleged psychic from the former Soviet Union. All of that is connected to the legacy of her family’s experiences under state-sanctioned antisemitism. But how exactly these things are connected can’t be distilled into a concise explanation. Intergenerational trauma is much too slippery for that.

JC: What research was involved in writing the scenes set in East Hollywood bars like Salvation and tracing the drug scene and sobriety networks in Los Angeles?

RM: I’ve lived in Los Angeles for most of my life, from the time my family immigrated from Moldova in 1993 until I moved to Boston for a few years in 2018. I’ve done my time vibing with fellow misfits in hazy bars. LA is such a beautifully weird place. It’s equally likely that the screenwriter you meet at your friend-of-a-friend’s birthday drinks has a deal with Netflix or is collaborating on an erotic Harry Potter musical with his dentist.

My pharmacy school education gave me a lot of esoteric knowledge about the legal requirements of dispensing opioids and benzodiazepines and how my narrator could scam the system. And, without getting into too much detail, I can say that my experiences as a clinical pharmacist helped me intimately understand how substance dependence looks and feels and how it’s treated. I wasn’t comfortable writing about marginalizing experiences outside of my own or those of people I was in community with.

Every word that made its way into the final draft fought tooth and nail to be there.

JC: Did you travel to Moldova, your birthplace, or recall scenes from previous travels to write about the narrator’s journey there with her psychic girlfriend Sasha?

RM: In July 2019, I visited Moldova with my parents for the first time since immigrating when I was two. I had no memory of my birthplace, so I was essentially experiencing it for the first time. Itinerary-wise, my trip was very similar to the narrator’s. I visited the Jewish cemetery in Kishinev, which was as grim and run-down as I described in the novel. I saw the abandoned banquet hall where my parents got married, the hospital where I was born, and my parents’ former schools and apartments, including the one where we lived right before immigrating. I visited Saint Petersburg as well, and while we were there, the queer activist Yelena Grigoryeva was murdered, just as I described in the novel.

I took that trip a few months before I started reworking what was then a linked story collection into the novel that became All-Night Pharmacy. I have no idea what this novel would have become, if it would have existed at all, had I not taken that trip. And between the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s genocidal war in Ukraine, I don’t know when I’ll be able to visit the region again.

JC: Your narrator works night shifts in an emergency room at her therapist’s suggestion. Was your work as an HIV and primary care pharmacist useful in writing the ER scenes? Is this where your title comes from?

RM: Working as a hospital pharmacist for several years was totally instructive for writing the novel. Though I didn’t take care of ER patients on a daily basis, I did respond to code blues (patients in cardiac or respiratory arrest), many of whom were in the ER. So I had a sense of how ERs function and how the narrator could lose and find herself in the work.

As for the title, the image of an all-night pharmacy, with a neon open 24 hours sign set against a dark LA sky, felt fitting for a novel where our narrator is always out too late in places she shouldn’t be with people who don’t have her best interests in mind. The narrator, with her prescription drug scams, is an all-night pharmacy herself. And recently, the writer Maria Kuznetsova observed in an interview that my book is a sisterhood story, a queer-coming-of-age story, an immigration story, an addiction-and-recovery story, and a detective story rolled into one—like an all-night pharmacy, there’s all kinds of shit in there.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

RM: I have a second poetry collection that’s basically done and which I hope to start shopping around soon. I’m working on some personal essays and interviews with authors I admire. I haven’t figured out my next book-length project yet. Hopefully another novel! I need a new voice to grab me by the throat. It’s the only way.

__________________________________

All-Night Pharmacy by Ruth Madievsky is available from Catapult.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.