Rural Stories That Get it Right: A Reading List

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips on Country-Based Fiction

Living out in the country has a rawness to it, but rural people don’t know it any other way. As Thomas Hardy wrote in Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the milk from the country dairies was too strong for city people and had to be watered down. As someone who grew up in a rural working class community, I believe this intimacy with rawness comes from a communion with the cycles of the natural world. And there’s no better example of that than agricultural life. People who work the land with their hands, who make do with what they got, who know all the secrets of violence and love—those are the people we all came from at some point. At the bottom of it, if we’re willing to look hard enough, we’ll see we’re all just country people, coming from a long line of improvisers trying to survive.

My debut collection of short stories, Sleepovers, explores the isolated community where I grew up in northeastern North Carolina—a handful of tiny mile-long towns and fields and woods beyond them. My family still grows soybeans, corn, wheat, and peanuts, as many do back home. But when I left for college, I started to realize all the ways my culture is misrepresented, made fun of, exploited, and forgotten. Finding authentic rural representation in fiction (seeing farmers on the page) meant the world to me, and gave me permission to write my stories from home. I could go on and on about the importance of this, but here’s some of my favorite rural stories in fiction so you can see for yourself.

*

Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess is the oldest child in her rural working class family and they’re struggling to get by. And one day while driving the family’s only horse to the market, an accident happens and the horse dies. Guilt-stricken Tess sets out to do whatever she can to keep her family alive. So starts this remarkable novel and sets up pure young Tess’s fate, trapped by the circumstance of a place and class she never asked for. Hardy, a critic of industrialization and rural labor laws, fought to get Tess published despite the controversies it raised within conservative circles—giving us a triumphant and breathtaking portrait of a young rural woman’s resilience.

Alice Walker, “Everyday Use” from In Love and Trouble

Born to sharecroppers in rural Georgia, Alice Walker grew up in a storytelling tradition which rings out clear as a bell in “Everyday Use.” The discerning narrator, Mama, introduces herself to the reader: “One winter I knocked a bull calf straight in the brain between the eyes with a sledge hammer and had the meat hung up to chill before nightfall.” And even though Mama doesn’t have any schooling past the second grade, her perception spans the universe. So what happens when Mama’s college educated, city living daughter returns home for a visit? This incredibly powerful story explores the complications of inherited familial and cultural histories. And it’s one of the most important short stories you will ever read.

Mark Richard, “Strays” from The Ice at the Bottom of the World

It’s hard to come by stuff in the country like money and cutting edge doctors and schools. At the start of “Strays,” Mark Richard’s young narrator reveals that his mentally unstable mother has gone missing in the corn fields, his father’s left to go find her, and him and his brother stay up at night listening to stray dogs lick the leaking house pipes. Their nearest family member with a car is Uncle Trash and he shows up to “look after” the boys. “Strays” stunningly details the pains of being left behind one hot summer, but it also uncovers the ingenious joys of it.

Mary Hood, “How Far She Went” from How Far She Went

The title story from Mary Hood’s debut collection begins as a seemingly ordinary afternoon with a self-sufficient granny and her estranged granddaughter. The granny hangs boiled dishrags out on the line, scatters corn for the chickens, and cleans her daughter’s grave amidst her granddaughter’s whiney “I-hate-the-country” bickering. But before you know it, “How Far She Went” turns into a terrifying, action-packed pursuit, demonstrating the boundless lengths of love.

Alice Munro, “Boys and Girls” from Dance of the Happy Shades

A haunting coming-of-age story shimmering with the realities of country life, “Boys and Girls” is told from the point of view of a nameless narrator, recounting her childhood on a fox farm. And the everyday details are hardcore. “I was too used to seeing the death of animals as a necessity by which we lived,” the narrator says. Munro, herself, was raised on a fox farm in rural Canada so there’s no doubt she’s transcribing her own life here and exploring its psychological effects, which makes “Boys and Girls” even more potent.

Randall Kenan, “The Origin Of Whales” from Let The Dead Bury Their Dead

Randall Kenan was raised by his grandmother among the soybean fields of eastern North Carolina. “The Origin of Whales” from his fearless debut collection, Let the Dead Bury Their Dead, details the special kind of relationship that serves as the backbone for many rural people; the love between an elderly family member and a child. Here, Thad is dropped off for the night at his great Aunt Essie’s. And even though Thad doesn’t particularly like the collards she makes for supper, they disappear from his plate as soon as Aunt Essie starts telling him a story about collards from long ago. “The Origin of Whales” serves as a testament to the importance of storytelling and sounds and reminds us that (if we’re willing to pay attention) the most unassuming is really the most remarkable.

Bette Howland, “To The Country” from Calm Sea And Prosperous Voyage

While Bette Howland is known for being a Chicago writer, in “To the Country” her nameless protagonist visits her country cousins on a Midwest poultry farm. Over the “steady muttering hum” of the exhaust fans in the chicken houses, the protagonist details the devastating effects of capitalism within the agricultural industry, particularly in the lives of her cousins who “regularly seemed to be starting from scratch.”

Inès Cagnati, Free Day

Fourteen-year-old Galla has an absent mother, an abusive father and a slew of younger sisters. They all live together on a marshy isolated farm and she’s the only one of them to go to school, having won a scholarship. But she has to ride a rusty bicycle some twenty miles to get there. And when she gets there the other girls make fun of her hand-me-down clothes. Written by Inès Cagnati, a self proclaimed lifelong outsider who grew up in similar circumstances in remote France, this astonishing novel details what it feels like to be of a place and class that never wanted you. And despite all the harsh truths, how the heart miraculously keeps fighting to be loved.

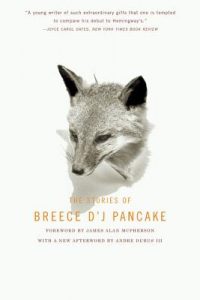

Breece D’J Pancake, “First Day of Winter” from The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake

Hollis stayed home to take care of the farm. His brother left for the city. But now the farm is failing, his aging parents are slipping fast and it’s the first day of winter. Snow’s gonna fall soon, leaving Hollis even more trapped and alone, with nothing but time and the “brittle, open, dead” land to wrestle with.“First Day of Winter” concludes Pancake’s only collection, published after he passed. Giving voice to the sacrificial mentality so deeply embedded in rural life, this story is one of the best pieces of fiction I’ve ever read. I can count on one hand how many times other short stories have touched me like this.

__________________________________

Sleepovers: Stories by Ashleigh Bryant Phillips is available now from Hub City Press.

Ashleigh suggests donations to the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network. NCEJC is a grassroots, people of color-led coalition of community organizations and their supporters who work with low income communities and people of color on issues of climate, environmental, racial, and social injustice. ncejn.org/donate/

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips is from Woodland, North Carolina. Her stories have appeared in The Oxford American, The Paris Review and others. Her first book, Sleepovers, is the winner of the C. Michael Curtis Short Story Book Prize.