Ruminations on Love, Loss, and Art in Manhattan’s Unlikely Oasis of Peace

Patrick Bringley Finds Some Calm at The Cloisters

The day of my brother’s funeral was meant to have been my wedding day. We had booked the hall, hired the band; we had even been married, a stop at city hall a few weeks prior to the big white event. Tom and Krista were meant to have been our witnesses that day, but at the last moment the call came that Tom was too weak. And if we tied the knot at the Queens city clerk’s office instead? Too weak. This was June third, 2008. He died on the twenty-second.

My first date with Tara Lohr was on Valentine’s Day about sixteen months before. The timing was a bit of happenstance that embarrassed us both, so we compensated by eating at a greasy spoon diner called Big Nick’s. In the booth, Tara’s cell phone rang, and she picked up the call. “Saara!” said Taara, her Brooklyn accent suddenly flowing like harbor water under the Verrazano Bridge. “You back in Bay Ridge? Listen, I saw your mutha. I saw your mutha yestuhday.” I guess I really didn’t know this girl, who up to this point I had thought talked normally. This was good. This was surprising.

A month before, we had been strangers at a New Year’s Eve dance party. Not too long after, I was spending the night at her place uptown. Oh, those early days, when I would ride the A train to the last stop in Manhattan and feel that the air was actually thinner up there! I would climb the stairs to her fourth floor apartment, knock on the door, and enter surely the most secluded spot in the whole city. Tara would rise at dawn to prepare for her job as a schoolteacher in the Bronx.

Half awake, I would watch her, picking out her Ms. Lohr clothes, just so; getting her overstuffed backpack together, just so; coming to give me a kiss as a prince would Sleeping Beauty, and leaving me alone in that small, sacred apartment. Sacred in the sense of “set apart.”

The beautiful melancholy of the echoey room suited us, though we were too happy to be somber.

Around the corner from her building, high up on a forested hill, loomed the Cloisters, an annex of the Met at the northernmost tip of Manhattan. On another of our early dates, we climbed the hill, huffing and puffing and saying the same things everyone must say while advancing toward the unlikely museum: “Can you believe we’re still in New York?” Emerging from the woods, we took in the weathered gray stone building modeled on a thirteenth-century abbey. Then we climbed still more, up the Cloisters’ winding staircase that in my memory, anyway, was torchlit. We donated $10 between the two of us, which felt generous, and entered the first of the museum’s medieval sanctuaries.

It was a twelfth-century French chapel built of heavy stone blocks. Small and little ornamented, it had a somber sort of grace. Tara, a former Catholic school girl, a Brooklyn Italiana, compared it favorably to St. Anselm’s on 82nd Street, which made me laugh. Taking my hand, she led me to the altar, pointed out where the tabernacle would have been, spoke about her God-fearing years with lightness, nostalgia, and eye rolls. Evidently she lacked the reflexive hush I exhibit before churchy things. But we were both enchanted. The beautiful melancholy of the echoey room suited us, though we were too happy to be somber.

I had visited the Cloisters before, but somehow the precise definition of a cloister eluded me. I would have guessed it was a tiny cell where a monk shut himself away to pray. In fact, a cloister was the open-air center of a monastery, a place set apart from the wider world but not from the sun, moon, and stars. The first cloister we visited, from twelfth-century Catalan, was a garden bursting with flowers.

It had fruit trees full of songbirds, pathways intersecting at a central fountain, a colonnaded perimeter constructed of pink marble. Monks would have crossed through it on their way to the refectory or the dormitory. Or they would have rolled up their sleeves, grabbed their spades, and tended this isolated garden, their own little patch of creation.

As Tara and I walked across the smooth pavers, she subtly practiced tap dance steps, a habit of hers. Pointing out some flowers, I told her that my Cub Scout troop in suburban Chicago used to make us sell tulip bulbs door-to-door. She found this amazing. Under a crab apple tree, she described growing up with two siblings in a third-floor one-bedroom apartment, her grandmother (from Abruzzo) on the first floor, her great-grandmother (“Mammucia”) directly downstairs, a fig tree in their tiny, scrubby yard.

She led me into the adjoining chapter house (a meeting place for the monks), and we sat on benches too short for her five-foot-ten-inch frame. Here, we could look out at the garden while feeling hidden in a shadowy place, its ceiling a network of rib-vaults like the tentacles of a giant squid. Relishing the chance to rest, Tara told me she and her friends used to hang out in the chapter house “all the time.” Now it was my turn to be amazed.

“You mean in high school? Hadn’t you moved to Staten Island?”

She had. But she attended a magnet public school in Manhattan, which meant that every morning she took the city bus to the Staten Island Ferry to the subway to get to school—a two-hour commute. This inured her to even the longest intra–New York journeys, so she and her friends (also outer-borough kids) thought very little of meeting up in midtown and riding the A train all the way up here.

“But why here?” I pressed.

“We were poets,” she said, laughing. “Or we thought we were. It felt like the ends of the earth, like a secret place. I had my fifteenth birthday right here. I wore a black spiderweb dress, and I don’t think we did anything but lounge on these benches and talk.”

We laughed at the recollection like it was a very long time ago, though we were then only twenty-three.

We walked through the next several galleries without stopping. If I had been alone, I would have paused to pour over the Mérode Altarpiece and study the Bury St. Edmunds cross. But Tara isn’t an “art person,” not really, and there were more pressing beauties to think about. We stopped when we arrived at a second cloister, with an outrageous view. Instead of being encircled by the museum-monastery, we were now at its edge, looking down at the Hudson River flowing against the Palisades. I had the strange sensation I could see us from high up above, standing at the narrowest part of a skinny island, watching the great river run slowly toward New York Harbor. It was like I could see the clear, crisp outlines of the love story we were writing.

It was like I could see the clear, crisp outlines of the love story we were writing.

“You wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for the harbor,” I reminded Tara. (Her father, a sailor, met her mother while docked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.) The clarity of the true statement felt incredible. It felt miraculous that, the next day, we would ride under the length of Manhattan and over the East River to her grandmother’s house for Sunday dinner. And that the following weekend we would zip over to Queens and visit with Tom and Krista, our elder statesmen in love.

We took a turn through the herb garden, laughing at soapwort, wormwood, black horehound, all the witchy names. Then we left the Cloisters and climbed back down the hill.

*

Eight months later, we announced our engagement in Tom’s hospital room, a merry cloister that day. We smuggled in beer and toasted with plastic cups. Tom’s face was all lit up with surprise.

And only four months after that, Tara and I took our turns sitting vigil by his hospital bed, watching television on mute as he slept.

On one of these nights, it was Krista, Mia, Tara, and I watching over Tom. It was late. He was seldom cogent anymore. But all of a sudden he lifted his head and demanded some Chicken McNuggets. I don’t know that I’ve ever been happier than when I charged out into the Manhattan night and returned with a great bounty of dipping sauces and breaded meat. Around the bedside, we picnicked, a loving, sad, laughing little group, managing the best way we knew how.

Looking back, it makes me think of Pieter Bruegel’s great painting The Harvesters. In that picture, a handful of peasants take their afternoon meal against the backdrop of a wide, deep landscape. There is a church in the mid-ground, a harbor behind, gold-green fields rolling back toward a distant horizon. Closer to the picture plane, men mow the grain with scythes and a woman bends low to bundle it. And at the nearest corner of the foreground, these nine peasants—comical and sympathetic—have broken from their labor to sit and sup beneath a pear tree.

Looking at Bruegel’s masterpiece I sometimes think: here is a painting of literally the most commonplace thing on earth. Most people have been farmers. Most of these have been peasants. Most lives have been labor and hardship punctuated by rest and the enjoyment of others. It is a scene that must have been so familiar to Pieter Bruegel it took an effort to notice it. But he did notice it. And he situated this little, sacred, ragtag group at the fore of his vast, outspreading world.

I am sometimes not sure which is the more remarkable: that life lives up to great paintings, or that great paintings live up to life.

__________________________________

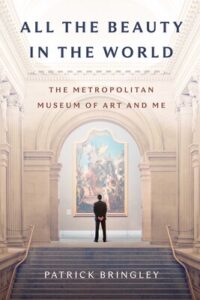

Excerpted from All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me by Patrick Bringley. Copyright © 2023. Available from Simon & Schuster.

Patrick Bringley

Patrick Bringley worked for ten years as a guard in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Prior to that, he worked in the editorial events office at The New Yorker magazine. He lives with his wife and children in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. All the Beauty in the World is his first book.