Rough Drafts: Writers at Work at the Millay Colony

The First in a Behind-the-Scenes Series on Residencies Across America and Beyond

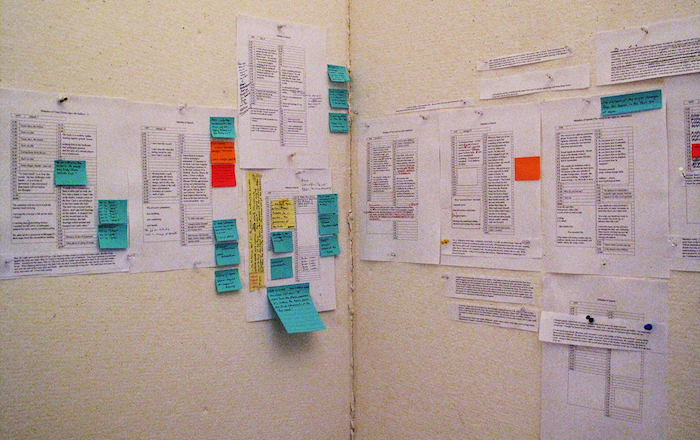

In the first of a series looking at the work being done at writing and artists’ residencies across America (and beyond!), we’re checking in with the Millay Colony for the Arts in upstate New York (about two hours north of NYC). We asked several recent alums from Millay to give us a window into their works-in-progress, from first inspiration, to the scrawl of edits, to final drafts. (The deadline for applications to the next season at Millay is March 1.)

![]()

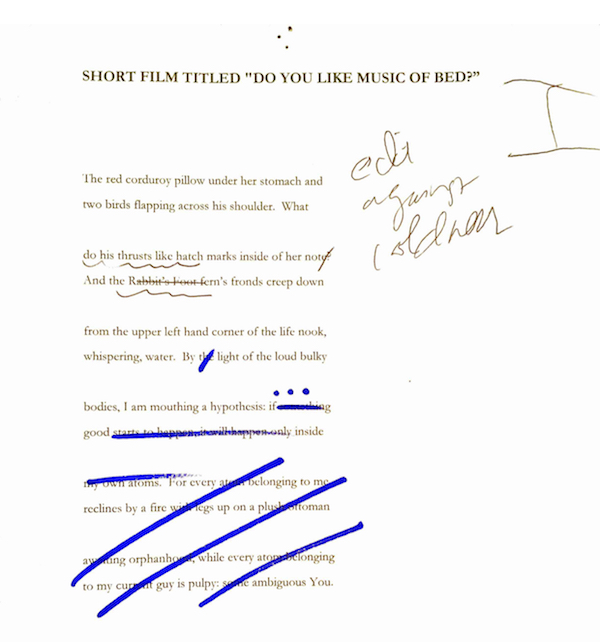

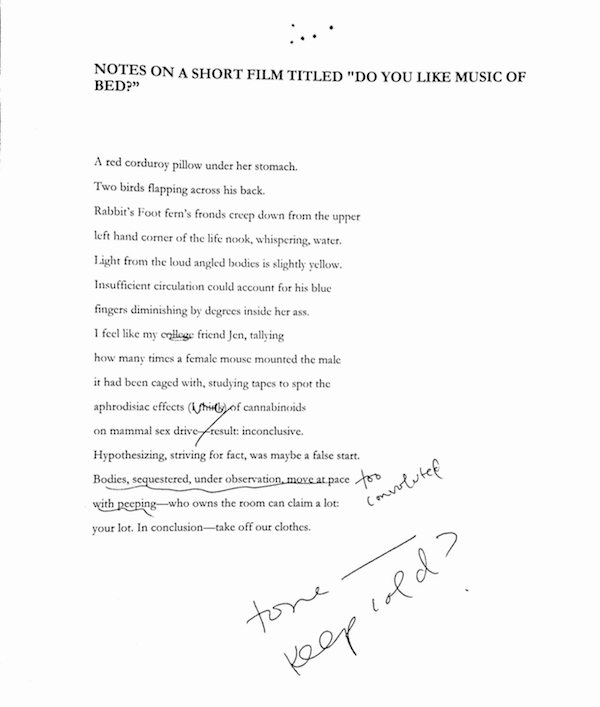

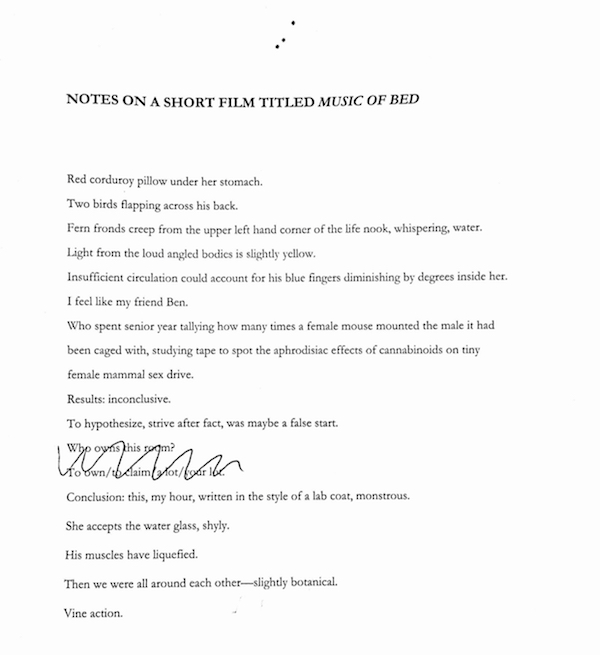

Rennie Ament studied poetry at Hunter College, where she has gone on to teach creative writing. Her work has appeared in Colorado Review, Queen Mob’s Teahouse, The Journal, and elsewhere. She lives in Astoria, Queens and works as a Program Assistant at Poets House in Manhattan. She runs the Roots Reading Series in Brooklyn.

Work in progress: Music of Bed, notes on a short film.

“Music of Bed evolved from a sex poem I’d written pre-Millay that was full of iffy botanical similes. I thought cold/clinical language might be better for describing a one-night stand…

I like that my friend Ben is in this. He really did spend a lot of time in college stoned and watching night vision mouse porn as part of his thesis research. There’s a more recent version of this one where the sex is transposed into the landscape, a little like that Russell Edson poem “Conjugal,” where a man is “bending his wife” around the room and eventually fucks her, literally, into the wall.”

![]()

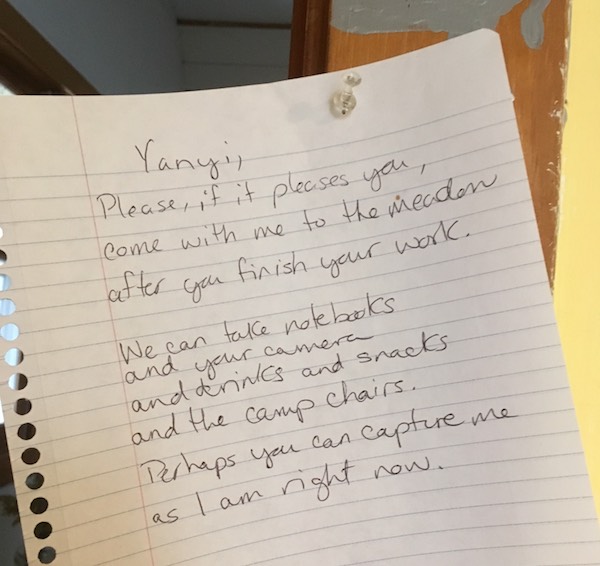

Yanyi serves as senior editor at Nat. Brut, contributing editor at Foundry, and curatorial assistant at The Poetry Project. His poems and criticism have appeared in Model View Culture, cellpoems, and The Shade Journal, among other journals, and he has been named a 2017-2018 Margins Fellow by the Asian American Writers Workshop.

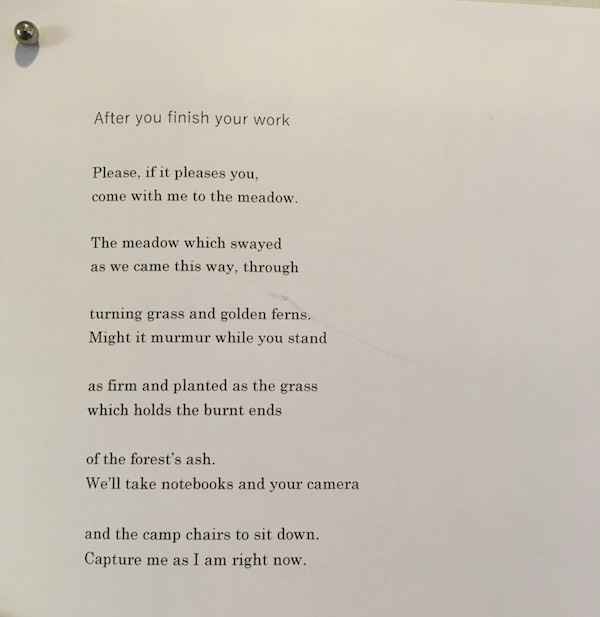

Work in progress: After you finish your work, a poem.

“One day this past September, I opened the door to my studio and saw this note from fellow resident and writer, Megan Gillespie. Megan has a deep presence with words and language, and working next to her at Millay reminded me of how expansive and full a day or poem could be. I read this note, full of its own rhythm and sweet invitation, and the poem followed. It is a callback to the offerings and ordinariness of our new friendship, after the beauty of Megan’s words in themselves. I have since made a line edit or two, and the poem was still up at Millay this January, where I spent New Year’s there as a Winter Shaker.

![]()

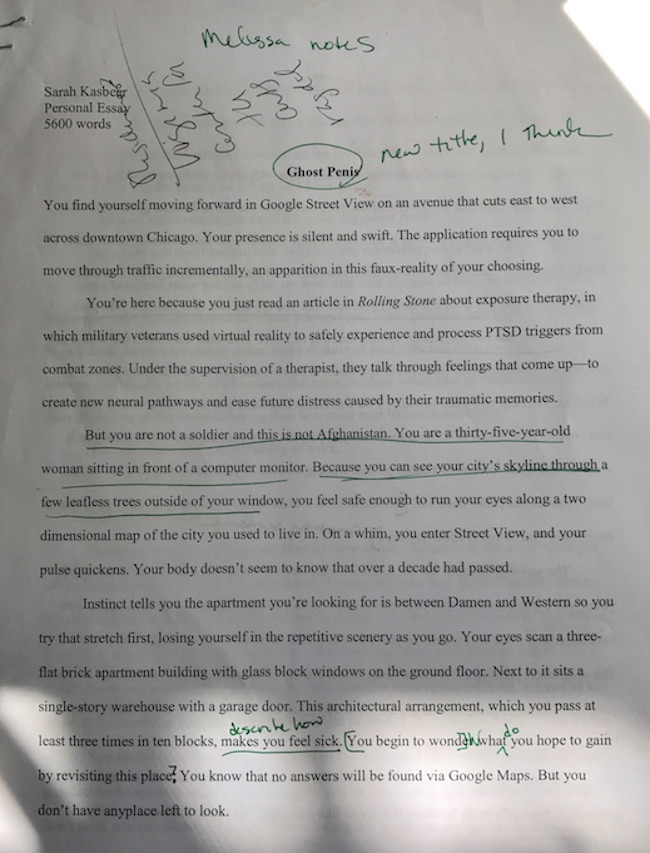

Sarah Kasbeer’s nonfiction has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Elle, Vice, Jezebel, Salon, and elsewhere. She currently lives in New York City and is working on a book of personal essays.

Work in progress: “Ghost Penis” (working title at the time), personal essay.

“I went to Millay Colony in May of 2017 to work with Melissa Febos on an essay about how my sex life had been haunted by a rape from my past. My draft—aptly yet unfortunately titled “Ghost Penis”—has since been revised, retitled, and placed for publication with The Normal School. It turned out to be the linchpin in a collection of essays I also worked on over the long weekend in my studio, about coming of age in a culture of misogyny, which I am currently looking to place. I definitely didn’t expect either to be published in a world that already feels distinctly different from the one in which it was conceived.”

![]()

Eva Heisler is a Maryland-born poet and art critic who currently works in Germany. She has published two books of poems: Reading Emily Dickinson in Icelandic (Kore Press) and Drawing Water (Noctuary Press). She edits the visual arts section of Asymptote, a journal of world literature in translation.

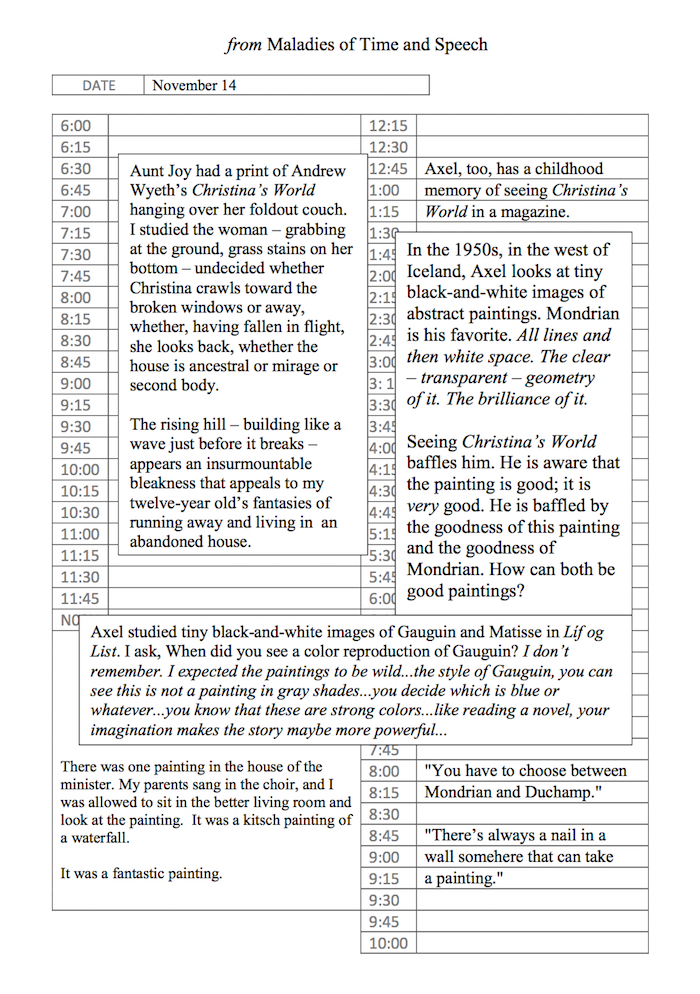

Work in progress: Maladies of Time and Speech, hybrid art and writing.

“Maladies of Time and Speech, a hybrid work-in-progress, is a sequence of daily planner pages. For now, and this may change, each page is a grid above which floats a constellation of field notes, journal entries, snatches of dialogue, vocabulary lists, and Icelandic grammar exercises. The work is so new that I have yet to figure out what is happening, but the work records encounters with artists and art in Iceland, my struggles to reconcile the making of poetry with the construction of something called “art history,” and glossophobia as a problem of time.”

![]()

Seema Yasmin is a poet, doctor and journalist from London currently living in the US. She was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2017 for her reporting with the Dallas Morning News. Yasmin served as an officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention where she investigated disease outbreaks in prisons, bordertowns and tribal reservations. Winner of the 2016 Diode Editions poetry chapbook contest, Yasmin’s poems appear or are forthcoming in Glass, Coal Hill Review, Bateau and The Shallow Ends, among others. She is working on a memoir about epidemics, her first full length collection of poems, and a biography of an AIDS scientist which will be published in 2018.

Works in progress: poetry.

I wrote one of these poems on the Amtrak train as it chugged out of Yonkers station towards Hudson. I was hours away from starting my residency and still a hundred miles away from the Millay Colony, but the promise of time and silence at Edna’s home and the thrill of two whole weeks in a writer’s studio, gave me the freedom to start writing on a seat back table. Other poems were written on the bench outside the main lodge, as the sun was melting the snow and I was thinking about sweet, rotting mangoes.

They Sell Neem Sticks In Whole Foods

corporate twigs shrink-wrapped

by white machines. I used to chew

miswaak like a Prophet. Girl arranging

tree branches in the yellow cup with

toothbrushes beside the kitchen sink.

Holy sticks carved by brown fingers.

Grandma soaked them for three nights,

scored the wet ends with a vegetable

knife. She used to say, smell what he

tries to sell you in case it is already yours.

Then she made us spit bloody Colgate,

massage gums with damp wood. Planted

frayed roots inside my mouth, taught me

to chew on wood until I swallowed trees.

I bought a neem stick in Whole Foods.

I laid it on the conveyor belt between

truffle oil and salty caramel, drove it

home and soaked the stick in a mason

jar in the guest bathroom where I would

forget. Two weeks later my sister came

to visit. We found the stick had bloomed

a brown mushroom. We fried it with ghee

and parsely in a Spanish omelette. Ate it

stuffed between two puffed up rotis.

Some English

My grandmother is dying

and the nurse wants to

know if we speak English.

My sister hisses like a cat,

sucks in the air behind

her Louis Vuitton niqaab

and turns back to flipping

the pages of New Scientist.

Tell him you wrote a thesis

on Thomas Hardy, an aunt

tells her daughter who tells

the nurse: We speak a bit.

The nurse wants someone

to translate the lunch menu

for Mrs. Khan in bed six.

But we don’t speak her

dialect. My grandmother

is dying and we are breaking

the rules. Sixteen robed women

oscillating around a bed which

lies beneath a sign that says:

Maximum two visitors at any time,

please. We pretend we don’t read

English. When the spirit catches

Short Aunty, a box of incense

goes flying. Jasmine and rose

scatters across the ward. I crawl

beneath blue curtains to gather

the scent. Mrs. Smith in bed two

clucks her tongue at our mess.

I point to empty chairs next to her

bed and ask if we can borrow

them—in the Queen’s English.

Mango Pickle

Our sweet fruit is growing black

on the trees & Zafar keeps picking

his scabs. This heat tastes of gangrene—

honey sweet on the lips, vinegar

at the backs of our tongues.

Zafar said the boys pushed him,

knees, palms shredded across

the playground. My child

bandaged his skin, gritty

& minced, beneath polyester

trousers—until I sniffed

wounds sweating a ripe pus.

The mango farmer has left the village—

his wife said he won’t be coming back.

She wrote pestilence on the divorce paper,

the judge searched for a stamp that said

blight. Mangoes won’t leave the trees—

their soggy stems keep swelling thicker.

My Zafar whimpers in his sleep.

I try to turn black fruit to pickle,

crack hair from stone, drain

bitter juice into jam jars.