Romance and Representation: On the Rise of the Asian American Romantic Comedy

Jeff Yang in Conversation With Actor Simu Liu and Filmmaker Alice Wu

It took a while for stories of Asian love to make it to American screens, but once they crashed the party, movies like Crazy Rich Asians and Always Be My Maybe showed that Asians are quite capable of delivering the swoon. In this Q&A, actor Simu Liu (Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings) and filmmaker Alice Wu (Saving Face, The Half of It) talk about the racial politics of romance, the aching need we sometimes have to touch and be touched, and the ways in which love is a many-splendored—and gendered—thing.

*

We’ll get right into it. Why do you think it took so long for Asian American romances to appear on-screen?

Simu Liu: Well, historically, cinema has been framed from a predominantly white male perspective. That means Asian male characters would rarely be three dimensional or aspirational, much less romantically appealing. And meanwhile, Asian women were often fetishized as docile, submissive sex objects. You can see how that combination might serve as an obstacle to depicting Asians through a romantic lens. I can’t say that I even remember seeing two Asian people kissing in a Hollywood film until I reached adulthood.

We’re telling these stories as a kind of proxy for that abundance.

Alice Wu: But most Asian American indie films haven’t focused on romance either. And I think there are reasons for that: Ours is still a majority immigrant community, and if you’re the new kid on the block, that first generation basically has to just figure out how to survive. Romance is not practical. In a lot of ways, it’s the opposite of practical. So maybe it takes two or three generations to get to a point where you’re ready to make romance a focus, something you can tell stories about. And I think American romantic cinema is a late bloomer—but as a result, our romantic movies contain all the beauty and the pain of being a late bloomer.

I can see that. A lot of us—not all!—were definitely slower to experience romance than our non-Asian friends.

Alice: Well, I was a very quiet kid, and we moved every two or three years. And so I ended up being more of an observer than a doer. I’d see people who really knew how to work it and were popular and socially integrated, and I was always so impressed. I was like, “Wow, how did they do that?” Because I had zero idea. I ended up watching movies to try to understand them—like, “What is this world they belong to?” And now maybe I’m making movies to try to understand them?

Simu: But movies and TV didn’t reflect the world we actually lived in. I was big into, you know, teen dramas, all the shows featuring brooding white emo kids. And even though I didn’t see myself depicted in them, some of their themes translated over to me. Oh, so the jocks are the cool kids? And the cool kids get girlfriends? I guess that means I have to be good at sports and go to parties and try to be on top of the social hierarchy. And because I’m Asian and I’m fighting the shadow of Long Duk Dong, it’s even harder: I have to be really good at sports, go to a lot of parties, and be at the very top of the social hierarchy if I want to have romantic options at all. Everything I saw in the media portrayed me as undesirable, so my assumption was that in every room I walked into, that was something I had to overcome. I guess that’s the textbook definition of an inferiority complex, but that’s what these depictions of dorky Asian sidekick characters instilled in me.

I suppose we didn’t have a lot of role models for romance—on-screen or off.

Simu: Well, I think as children of immigrants, you don’t always have parents who are touchy-feely, or open about physical affection, with each other or with you. I’d sometimes look at my friends’ families, and I’d look at white families on TV and think, Damn it, why isn’t my family more like that? Why isn’t my house just full of physical affection being given in abundance? And maybe that’s why we’re seeing this recent Asian American rom-com renaissance. We’re telling these stories as a kind of proxy for that abundance.

Alice: I guess for me, the lack of romantic models has led me to make movies that all ask the same question: Is it even possible to have romantic love and love for your family, and have them coexist peacefully? Because as an Asian lesbian, that did not seem possible in, you know, the year 2000. Now it seems possible, but not then. And maybe that’s why I don’t really make romantic comedies in the traditional sense, where “getting the girl” is the most important thing. For me, the key relationship is not actually the romantic couple, but two other people. Like, Saving Face is really a “romance” between a mother and a daughter. And The Half of It is really a “romance” between two friends. The romantic plot acts as a red herring that makes you consider the impact of romance on others.

People tend to think of romance as just fluff, trivial stuff. But it has ripple effects on everything around us.

Simu: There’s a reason why most Hollywood stories revolve around love and romance, to some degree! Which, of course, is part of the reason why Asian men have not had so many chances to be leading men—it’s directly linked to the fact that nobody sees us as romantically viable. In most Hollywood movies, romance is an intrinsic part of being a cinematic protagonist. You can’t just be funny or interesting or competent; you can’t just fix problems or defeat the villain. Audiences also expect you to “get the girl”—or guy—at the narrative’s end. And if the powers that be can’t imagine you doing that, you’re probably not getting cast as the lead.

Part of what romance means to me is coming to the realization that things can never truly be perfect, but standing your ground.

Alice: But the rising tide of romantic comedy lifts all boats! I loved that in Crazy Rich Asians, the Asian men were all very sexy and hot. I loved it even though I’m not attracted to men, because I love that Asian people can be seen as attractive or sexy, no matter their gender. And that Hollywood looked at the results and said, “Oh, that movie made money! Let’s make more Asian stories!”—the fact that that’s what it took to finally break the dam still seems a bit ridiculous to me, but I’m grateful it happened.

At the end of the day, what do you think romance means to you?

Simu: Well, honestly, it’s something I’ve had to relearn over time. Growing up in the Western world, there’s this expectation that men need to take charge, be extroverted, and have these aggressive traits in romantic situations. And I look at Tony Leung, who played my father in Shang-Chi. He’s been the biggest male lead in Asia for decades, and he has this incredible ability to evoke romance with stillness and nuance. Part of it is just that there’s a different sense of what it means to be masculine in Asia, but part of it is also him being in a film industry where there was an abundance of opportunities to play romantic leads. For a lot of Asian Americans, we are only now getting our chance at bat, and the learning curve is high. As someone who grew up thinking the be-all and end-all of masculinity was the high school jock, one of the joys of getting older and attaining a degree of self-awareness has been learning that yeah, I don’t need to be that guy.

Alice: The learning journey is so important. Part of what romance means to me is coming to the realization that things can never truly be perfect, but standing your ground, sticking with it, and trying to make it work anyway. That’s true about movies too. Maybe that explains why I’ve only made two movies! I’m just a very monogamous filmmaker.

__________________________________

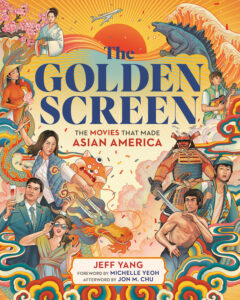

From The Golden Screen: The Movies That Made Asian America by Jeff Yang, foreword by Michelle Yeoh, afterword by Jon M. Chu. Copyright © 2023. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Jeff Yang

Jeff Yang has been observing, exploring, and writing about the Asian American community for over thirty years. He launched one of the first Asian American national magazines, A. Magazine, in the late nineties and early 2000s, and now writes frequently for CNN, New York Times, and elsewhere. He has authored three books—Jackie Chan’s New York Times bestselling memoir I Am Jackie Chan: My Life in Action; Once Upon a Time in China, a history of the cinemas of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland; and Eastern Standard Time: A Guide to Asian Influence on American Culture, and most recently coauthored the New York Times bestselling RISE: A Pop History of Asian America from the Nineties to Now. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.