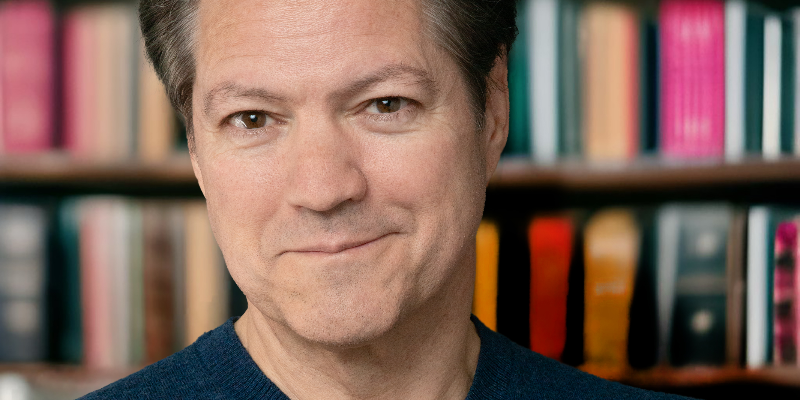

Robert Petkoff on Finding the Narrative Voice

In conversation with Jo Reed on Behind the Mic

Golden Voice narrator Robert Petkoff joins host Jo Reed to discuss his work in audiobooks and the career path that led him there. Robert has brought to life everything from thrilling mysteries and science fiction epics to deeply researched nonfiction. He’s able to create distinct and memorable voices for each character, and he has a knack for engaging storytelling. Listen in to his conversation with Jo to hear more about how he got his start on the stage and behind the mic, how he prepares for narrating fiction like Andrew Sean Greer’s Less is Lost, the fun of narrating thrillers, and the distinct skills needed for making nonfiction engaging and conversational for audiobook listeners.

From the Episode:

Jo Reed: Let’s talk about how you prepare narrating fiction, and why don’t we take Andrew Sean Greer’s book, Less is Lost, as an example.

Robert Petkoff: Love that book.

JR: Yeah, let’s talk about that. How do you prepare?

RP: Well, number one, you read the book. I once tried—I was doing the John D. MacDonald books, and we were doing all of them in a very short period of time, and I ran out of time in order to read the next book ahead, and I thought, I’m good at this. I know his characters. I can cold read this, and I got tripped up. There was a character that had a particular accent that John, bless him, only mentioned later in the book, and so I found myself going, oh, no. See, this is why I have to prepare because we had to go back and rerecord some dialogue and stuff. So, lesson one, always read the book, and then you get a feel not only for what the characters are going to be, but for the tone, for the whole overarching way the story should be told, or at least the way I think it should be told, the way I think the author wants it told. While reading through it, I will highlight each character. I use a little app called iAnnotate on my iPad, and I use a highlighter for each character, and that just helps me know that when I’m doing back and forth dialogue, or if I’m doing five people or even two people, I know exactly what voice is speaking right then and there. I don’t have to go back and go, oh, wait, wait, that’s the wrong character.

JR: Since Less is Lost is the second book about Arthur Less, the first one being Less, which you also narrated, did you try and recreate that voice of Arthur from the first book?

RP: Absolutely. I went and listened to Less to remind myself of how did certain people speak, and how did each character sound, because I wouldn’t imagine that a lot of people listen to Less, and then instantly listen to Less is Lost. Though I’m sure there are people that did that, that later on came to it and said, oh, I want to hear Less, and I want to hear that one. But even though there’s time between them, you want to get it right, and you want someone who remembers the characters to hear the voice in Less is Lost and go, oh, I remember that person, and they can bring a lot of what they felt about that person in the first book right instantly to the second book, and so I think it’s important to keep that consistency.

JR: Robert, what about landing on that all-important narrative voice?

RP: Ah, yeah. It’s so fascinating to me, because I think there is a wide variety of what that is. For different narrators, I know that some narrators try to come up with a very neutral sound, a neutral tone, as they narrate, because they don’t want to interfere with a listener’s own interpretation of what the book is, and I can’t do that. I have to, again, just as with nonfiction, I think, who am I talking to? With fiction, I have to think, who’s talking, who’s telling the story? And so I have to decide. Obviously, if it’s first-person narration, that’s easy, but third-person narration, I have to decide what’s the tone. If it’s a very lighthearted book, if it’s got a very easy sort of theme to it, then I would start the book maybe saying, “On July 3, 1944, Henry found himself”— just sort of this very relaxed, sort of easygoing thing. If I know that I’m narrating something that is going to have a heavier tone, I don’t want to betray the listener by setting them up to think that we’re going to be having a light romp through the woods, and suddenly it’s this heavy thing. At the same time, I don’t want to overdo it, and say, oh, I know this book has some heavy themes at the end, so I’m going to be really heavy for the entire book. An author writes each chapter with its own feeling, and they know what they want the reader or listener to discover, and so I try to discern what is that tone. But generally speaking, I do, as a narrator, try to keep things moving and try to keep things up, so that you’re not having a dirge as you’re listening to this thing, but again, trying to be conversational in many ways, if I can.

JR: Well, in both Less and Less is Lost, the main character, Arthur is traveling in the first book around the world and across the country in the second, and that gives you a host of characters of different accents to perform. Was that daunting? Was that fun? Was it both?

RP: It’s fun. I mean, it is daunting in that you want to get it right, and you don’t want to get it too heavy. If it’s a German character, an Indian character, or anything like that, I never want to try to do like a full 100% characterization, because again, you want the listener to have some freedom of imagination with this thing. So you want to give a flavor, is how I think of it. I want to give a flavor of the dialect, so they think, oh, German, or whatever it is, and at the same time I want to be very sensitive to other cultures and other countries. I don’t want to do Hollywood’s version of an accent from 40 years ago that was rather offensive to people. So, I want to have the lightest touch when it comes to those things, and at the base of all of it, unless it’s a particularly silly sort of thing, I do want them to all sound like real people. So I give a flavor of the accent when I give it, but generally speaking, it is a joy when there are multiple characters from multiple places because there’s only so many places you can pitch a voice in my own voice, only so many flavors I have in my own natural voice, and so when there’s a different dialect, I’m like, oh, great, this helps to differentiate this character. This gives me a cheat in a way of making that character’s voice very clear.

Nothing is harder for me than having, say, five women talking to each other who all sort of are from the same place, because I want the listener to be able to know each particular woman’s voice, but I don’t have that many women’s voices in my voice, and in particular, when doing a woman’s voice, I don’t try to do some sort of falsetto. That’s so offensive. I just try to lighten my voice, and if it’s a woman, she talks like this. If she’s talking to a man, he’s here, and she’s talking here, just to give, again, a flavor that it’s a more feminine sound, perhaps. Unless the character is a woman that doesn’t demand a feminine sound, but it’s an adventure. It’s fun. My wife and I always joke about the character of Bottom in Midsummer Night’s Dream, “Oh, let me be the lion too.” Most actors were like, I want to play that part, and I want to play that part, oh, and I have an idea for that part. Well, that’s the beauty of narrating audiobooks, that you are playing all the parts.

JR: You get to be Bottom.

RP: I get to be Bottom. I get to be the lion, too.

RP photo courtesy of the narrator.

To listen to the whole archive of Behind the Mic with AudioFile Magazine, subscribe and listen on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, or wherever else you find your favorite podcasts.