Richard Hugo on Starting a Poem

“The words should not serve the subject. The subject should serve the words.”

A poem can be said to have two subjects, the initiating or triggering subject, which starts the poem or “causes” the poem to be written, and the real or generated subject, which the poem comes to say or mean, and which is generated or discovered in the poem during the writing. That’s not quite right because it suggests that the poet recognizes the real subject. The poet may not be aware of what the real subject is but only have some instinctive feeling that the poem is done.

Young poets find it difficult to free themselves from the initiating subject. The poet puts down the title: “Autumn Rain.” He finds two or three good lines about Autumn Rain. Then things start to break down. He cannot find anything more to say about Autumn Rain so he starts making up things, he strains, he goes abstract, he starts telling us the meaning of what he has already said. The mistake he is making, of course, is that he feels obligated to go on talking about Autumn Rain, because that, he feels, is the subject. Well, it isn’t the subject. You don’t know what the subject is, and the moment you run out of things to say about Autumn Rain start talking about something else. In fact, it’s a good idea to talk about something else before you run out of things to say about Autumn Rain.

Don’t be afraid to jump ahead. There are a few people who become more interesting the longer they stay on a single subject. But most people are like me, I find. The longer they talk about one subject, the duller they get. Make the subject of the next sentence different from the subject of the sentence you just put down. Depend on rhythm, tonality, and the music of language to hold things together. It is impossible to write meaningless sequences. In a sense the next thing always belongs. In the world of imagination, all things belong. If you take that on faith, you may be foolish, but foolish like a trout.

Never worry about the reader, what the reader can understand. When you are writing, glance over your shoulder, and you’ll find there is no reader. Just you and the page. Feel lonely? Good. Assuming you can write clear English sentences, give up all worry about communication. If you want to communicate, use the telephone.

To write a poem you must have a streak of arrogance—not in real life I hope. In real life try to be nice. It will save you a hell of a lot of trouble and give you more time to write. By arrogance I mean that when you are writing you must assume that the next thing you put down belongs not for reasons of logic, good sense, or narrative development, but because you put it there. You, the same person who said that, also said this. The adhesive force is your way of writing, not sensible connection.

The question is: how to get off the subject, I mean the triggering subject. One way is to use words for the sake of their sounds.

The initiating subject should trigger the imagination as well as the poem. If it doesn’t, it may not be a valid subject but only something you feel you should write a poem about. Never write a poem about anything that ought to have a poem written about it, a wise man once told me. Not bad advice but not quite right. The point is, the triggering subject should not carry with it moral or social obligations to feel or claim you feel certain ways. If you feel pressure to say what you know others want to hear and don’t have enough devil in you to surprise them, shut up. But the advice is still well taken. Subjects that ought to have poems have a bad habit of wanting lots of other things at the same time. And you provide those things at the expense of your imagination.

In the world of imagination, all things belong. If you take that on faith, you may be foolish, but foolish like a trout.

I suspect that the true or valid triggering subject is one in which physical characteristics or details correspond to attitudes the poet has toward the world and himself. For me, a small town that has seen better days often works. Contrary to what reviewers and critics say about my work, I know almost nothing of substance about the places that trigger my poems. Knowing can be a limiting thing. If the population of a town is nineteen but the poem needs the sound seventeen, seventeen is easier to say if you don’t know the population. Guessing leaves you more options.

Often, a place that starts a poem for me is one I have only glimpsed while passing through. It should make impression enough that I can see things in the town—the water tower, the bank, the last movie announced on the marquee before the theater shut down for good, the closed hotel—long after I’ve left. Sometimes these are imagined things I find if I go back, but real or imagined, they act as a set of stable knowns that sit outside the poem. They and the town serve as a base of operations for the poem. Sometimes they serve as a stage setting. I would never try to locate a serious poem in a place where physical evidence suggests that the people there find it relatively easy to accept themselves—say the new Hilton.

The poet’s relation to the triggering subject should never be as strong as (must be weaker than) his relation to his words. The words should not serve the subject. The subject should serve the words. This may mean violating the facts. For example, if the poem needs the word “black” at some point and the grain elevator is yellow, the grain elevator may have to be black in the poem. You owe reality nothing and the truth about your feelings everything.

_______________________________________

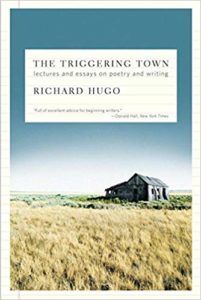

Excerpted from The Triggering Town: Lectures and Essays on Poetry and Writing by Richard Hugo. Copyright © 1979 by Richard Hugo. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Richard Hugo

Richard Hugo (1923–1982) was for many years the director of the creative writing program at the University of Montana, Missoula Campus. He received the Theodore Roethke Memorial Prize and was twice nominated for the National Book Award.