“Retribution Masquerading As Art.” Elissa Altman on the Problem with Revenge Writing

“Does it move the story forward? Does it belong in my journal?”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

When my father died suddenly and violently in 2002, I was treated so badly by a close and trusted family member—the one he always told me to go to if anything ever happened to him—that, in hindsight, it was almost comical. At a certain point, dreadful behavior becomes parodical; it devolves into a caricature unto itself, turning the perpetrator into a one-sided evil villain like Amy Elliott Dunne in Gone Girl, or Zenia in Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, who Lorrie Moore described in her 1993 New York Times review of the novel as Iago in a miniskirt.

And yet: in the writing of my first memoir, Poor Man’s Feast, a decade after my father’s death, I exacted my revenge by devoting forty pages to this person and her conduct, which I have worked for years to unknot from the grief over the loss of my father. In these pages, the narrative voice was rage-y and furious, the writing was bleating, flailing, and a mass of enraged, disconnected run-on sentences about who this person was and how terribly she had treated me. It was an accurate assessment, but when I delivered my finished manuscript to my editor, it came back to me with those forty pages sliced out like a cancer.

We went back and forth; I pleaded. She said I understand what you’re trying to say, but it has nothing to do with the story. After a few more rounds of digging in my heels, I relented and actually listened to her, and realized (with her help) that I needed to get to a place of creative comprehension: that the painful cruelty I had experienced at the hand of this person on one of the worst days of my life had to be transcended in order to get to a place where she could be rendered as the textured, complex character she actually is, and for the narrative to follow suit. My creative and emotional attachment to her betrayal had to be snipped like a wire, or whatever I wrote was going to risk being weighed down by an anvil of revenge and retaliation, unable to move forward, unable to evolve.

Revenge writing smacks of desperation, of the writer’s back being up against a wall and their coming out swinging. It is a shivering, panting dog that will do anything for a bone; it is out of options.

I begin every one of my writing workshops with the same questions: Why are you writing the piece you brought here? What is the motivation for wanting to craft your story? What are you hoping to achieve aesthetically and artistically? Most times, the answers have to do with wanting to attain clarity, or to make art from the human and mundane, or to leave a record. But once, a student workshopping a section of their memoir told me plainly: I want to write this memoir to exact revenge on someone. Why else would I do it?

I was stunned; no student had ever been that forthright. Admission of desire for revenge on the page also reeks of shame: it’s the thing that every writer—certainly every memoirist—grapples with but generally never talks about. Why else would I do it, my student had said, and those words hung in the air like humidity. I wanted to know: was he a reader of memoir? What did he get out of it? Because why else would I do it means one thing: he was writing specifically to inflict pain, damage, and retributive cruelty born of a playground mindset. You did this to me, and I’m going to do this to you, and everyone is going to be so interested in it and take my side either as winner or victim.

Revenge writing in memoir is never, ever a good, or valid, creative intention. Retribution masquerading as art inevitably fails at the foundational level; it deflates language, renders characters cliched and flat and lifeless. It dilutes human complexity and possibility from the story; it negates human frailty and the ambiguity that goes with it. It slows the pace and pulls the reader into the muck of someone else’s poison. There is a stark difference between the kind of gratuitous revelations that power revenge, and the revelations that actually drive the story forward, without which it would not exist.

In The Situation and the Story, when Vivian Gornick wrote For the drama to deepen we need to see the loneliness of the monster and the cunning of the innocent, she was not just talking about narrative balance; she was talking about the complex human condition that acknowledges our fallibility and imperfection: every single one of us has two sides, and those two sides must be evident in the way we craft our stories. Dorothy Allison was more reductive about it when she said, in a 2015 Tin House summer workshop I was attending, If you’re going to write a character as an asshole, you’d better be ready to write yourself the same way.

If I was certain that telling the story about my relative’s heinous behavior would get her back because she deserved it, I also had to ask myself: and then what? What comes next after revenge? How will a story unfold when it is bogged down by payback? How would my character move through her life if I was showing her as a one-sided malicious bully, and that’s all?

We may be enraged; we may be furious over the behavior of someone who has taken psychic possession of our story and won’t let it go. We may be obsessed with a long-standing resentment dying to see the light of day. But will revenge writing give the reader the fullest and clearest sense of who a character is at the human level, be they cruel or kind? No. Readers deserve this, and good memoir (and fiction) requires it. Revenge writing smacks of desperation, of the writer’s back being up against a wall and their coming out swinging. It is a shivering, panting dog that will do anything for a bone; it is out of options.

Writing about someone who has in some way harmed us is a minefield. When I do it now—if the story requires it and will wobble like a three-legged table without it—I step away from the work for a few days (or months, or years) and then ask myself these questions: Is it fair? What is my intention, and my motivation? Does it move the story forward? Does it belong in my journal?

I allow myself to get it out of my system—and this is advice I stand by; we’re only human—but unless I can answer those questions with clarity, I move on.

_________________________________________

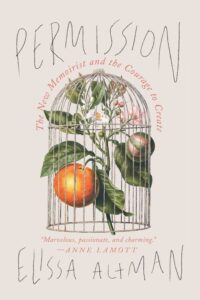

Permission by Elissa Altman is available now via Godine.

Elissa Altman

Elissa Altman is the author of the upcoming memoir, Motherland.