Respectability Be Damned: How the Harlem Renaissance Paved the Way for Art by Black Nonbelievers

Anthony Pinn Explores How James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, and Others Embraced a New Black Humanism

Much Black American literature up until the Harlem Renaissance sought to present Black life in a way that pointed out the damage done by racial discrimination and advanced a story of Black Americans as deserving full inclusion in the life of the country, as defined by white norms of sociality. To accomplish this, early Black narratives resisted a full depiction of Black life. Instead, they sought to project only the best—meaning those that could be read in line with white social sensibilities.

These narratives argued that departures from these standards were due to discrimination prohibiting the development of the best capacities of Black Americans. This approach to personhood changed with the Harlem Renaissance, an artistic movement spreading from Harlem, on New York City’s Manhattan Island, through areas such as Washington, DC, from the late 1910s to, roughly, the end of the 1930s.

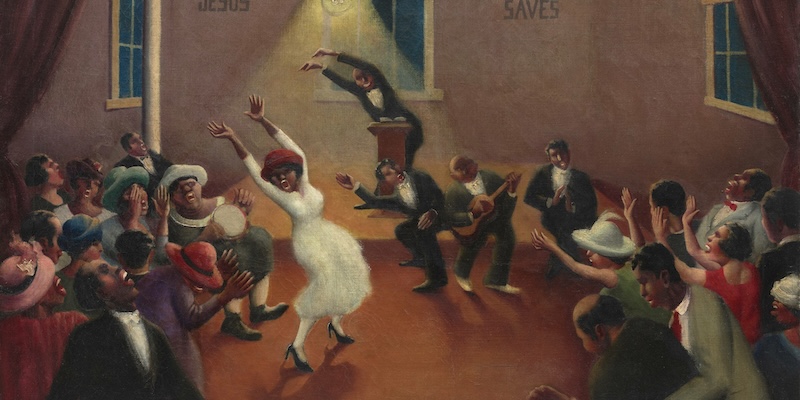

For Harlem renaissance artists, both visual and literary, advocacy for Black humanity involved pushing against the politics of respectability. Anything short of a full and vibrant presentation of Black life in all its complexities, joys, and sorrows was to limit Black Americans to a white idea of Blackness and render them one-dimensional for the comfort of a white audience.

This move toward complexity also involved recognition that not all Black life is associated with the moral and ethical sensibilities of Black churches; in fact, much of this literature is critical of the Black Church, exposing its inconsistencies, such as preaching a moral code that isn’t upheld by church members or leaders. In these stories, ministers aren’t the heroes, but are flawed individuals weighed down by trauma and adherence to the very worst principles of the social world.

Novelist and essayist Zora Neale Hurston’s depictions of relationships and communities demonstrate the pitfalls and promise of collectivities and mark out violent race, gender, and class-based encounters. What readers get with Hurston (1891–1960) is recognition of the cultural world(s) of Black theism(s) without the assumption that one must embrace it; vocabulary and grammar, signs and symbols, can be engaged without requiring conversion.

This move toward complexity also involved recognition that not all Black life is associated with the moral and ethical sensibilities of Black churches.

Reflecting the same thinking, James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) could note his conversion to disbelief and still write in God’s Trombones (1927) a moving ode to the Black sermonic style and imagery.

Hurston and Johnson serve as two examples of how the Harlem Renaissance often disentangled language from practice and, in this way, tamed the claims of theism, while using its grammar of wonder. In their work, language is simply a system of cultural signifiers that can be put to secular use to describe not spiritual commitment, but imagination along the horizontal frame of life.

Hurston could present, with energy and respect, forms of theism practiced by Black Americans in the Deep South without claiming personally a sense of their spiritual authority and power. She understood why some claim belief in god(s), but such a claim doesn’t seem of personal importance to her—although, at times, she participated in theistic activities as an anthropologist attempting to understand the dynamics of Black life.

On a personal level, there’s reason to believe that Hurston was content to use the resources available to her, those that had a certain materiality. “So,” she writes,

I do not pray. I accept the means at my disposal for working out my destiny….Prayer is for those who need it. Prayer seems to me a cry of weakness, and an attempt to avoid, by trickery, the rules of the game as laid down. I do not choose to admit weakness. I accept the challenge of responsibility.

This artistic depiction of life that didn’t assume the centrality of theism, but, rather, explored human existence from the vantage point of human history and experience, is not limited to literature. The visual and performative arts also expressed Black life through a focused presentation on embodied, mundane encounters that frame and highlight human meaning as earthy.

For example, “The Banjo Lesson” by Henry Tanner (1859–1937) presents the values of human existence, the nature of relationship, not in terms of verticality—that is, interaction between the divine and humanity—but through intimate encounter and human cooperation, as an elder teaches a young child how to make music.

Much of what I’ve presented to this point involves humanist-leaning sensibilities, but a forceful shift toward an explicit humanism takes place post-Renaissance, during what might be called “the period of Black realism.” When thinking of this period, one should keep in mind the work of literary figures such as Nella Larsen (1891–1965), Richard Wright(1908–1960), and James Baldwin (1924–1987). Some have argued that cultural production during this period maintained a connection to Black Christianity, if for no other reason than these figures continued to speak about it, reflect on it, struggle with it, rendering critique simply a way of stating Black Christianity’s value and importance by negation.

However, I think this is a weak argument, one that doesn’t take seriously the ability to think the world outside the spiritualization of language and intent. It is to assume there is no “outside,” no space beyond the influence and reach of Black Christianity. Critique by Black realism can be—and should be—understood as a negation and a movement toward the formation of life opportunity and identity free of theistic assumption.

Larsen, Wright, and Baldwin, among others, announce a new sense of self in relationship to the world; they hold humans accountable and responsible for their circumstances and for improving their life condition.

These authors expose theistic commitment and performance for the damage it does to the integrity of Black personhood. They highlight the manner in which adherence to church values, for example, comes at the expense of human health and well-being as suffering gets cast as the marker of human advancement and divine engagement.

Church devotion destroys productive human relationships, as Larsen’s novel Quicksand (1928) makes explicit. Helga Crane, the main character, moves from social disregard on the part of whites, and some Blacks, to an embrace of Black theism in the form of a country preacher and his church, only to encounter a death-dealing arrangement in which her value is reduced to the children her body produces. Prayer and service to the church do nothing but enhance her misery, and she eventually realizes why: God, and, therefore, God’s assistance, are an illusion. Crane is left to her own devices, responsible for her own well-being, and accountable for her own happiness.

As she is contemplating her condition—namely, a church community that hates her, a husband who only values her reproductive capacity, and children that consume her strength,

within her emaciated body raged disillusion. Chaotic turmoil. With the obscuring curtain of religion rent, she was able to look about her and see with shocked eyes this thing that she had done to herself. She couldn’t, she thought ironically, even blame God for it, now that she knew that He didn’t exist.

While not named as such explicitly, there is to be found in her resolve elements of the humanist principles presented in the first chapter of the book.

These authors expose theistic commitment and performance for the damage it does to the integrity of Black personhood.

In his nonfiction, including his memoirs Black Boy (1945) and American Hunger (1977), Richard Wright calls for humanism as a way to advance beyond the stagnation of human opportunity and creativity represented by racism and reenforced through the antihuman theologizing of theism—that is, Black churches. Better known than his nonfiction are works of fiction like Native Son (1940) and The Man Who Lived Underground (1941/42). Wright pushes against a theistically arranged set of values that urge obedience over critical thinking, and that diminish self-worth for the sake of heaven.

Wright calls for engagement with the material conditions of life—a rebellion against injustice that recognizes human accountability for the condition of the world, while noting that struggle against injustice may not be enough to end it. This stance is present in autobiographical form in Black Boy, where he reflects on his grandmother’s church:

Many of the religious symbols appealed to my sensibilities and I responded to the dramatic vision of life held by the church, feeling that to live day by day with death as one’s sole thought was to be so compassionately sensitive toward all life as to view all men as slowly dying, and the trembling sense of fate that welled up, sweet and melancholy, from the hymns blended with the sense of fate that I had already caught from life. But full emotional and intellectual belief never came. Perhaps if I had caught my first sense of life from the church I would have been moved to complete acceptance, but the hymns and sermons of God came into my heart only long after my personality had been shaped and formed by unchartered conditions of life. I felt that I had in me a sense of living as deep as that which the church was trying to give me, and in the end, I remained basically unaffected.

Rather than theistic optimism, Wright exposes hypocrisy. The church says things will change because God says so. Wright, in response, mocks such misguided thinking and calls for defiance as its own reward. While Black Christians speak of the great “by and by”—with death overcome through spiritual obedience—Wright asserts that there is nothing after death, and a painful death often comes despite our best efforts to pursue transformative values.

Unlike his Christian counterparts, for Wright the world is without reason; it shows no concern for humans, and it doesn’t respond to their questions, wants, and needs. As he recounts in Black Boy, Wright tried, at the request of his grandmother, to embrace the Christian faith, and, had he encountered theistic religion before the world, he would have been able to believe. But the harshness of the world, the conditions of Black life, made it impossible to embrace the unfounded claims and violent demands of Christian practice.

James Baldwin, on the other hand, grew up in the Pentecostal Church. As he recounts in Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), he pursued ministry as a way to shift the power dynamics in his home, which was run by an overbearing father. Moreover, because in Harlem everyone had to belong to something or someone, for him it might as well be the church.

However, that theistic community offered limited comfort and, with respect to his sexual urges, only fostered trauma; his sense of himself and his relationship to the larger world were warped by the puritanical demands of a religious community that failed to meet its own expectations. Baldwin eventually left the church, and, although he maintained some of the wonder he gained first in relationship to the theologizing of the church, his aims and orientation became more secular, more humanistic.

For these advocates of Black life’s complexity and richness over against the toxic qualities of white supremacy, a humanity-inclined approach to life afforded mental freedom and creativity, if nothing more.

One gets a sense of this in The Fire Next Time (1963) as he reflects on a visit with the Honorable Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam. Baldwin worried that he might be asked about his own faith commitment; he didn’t want to have to tell the leader of the Nation of Islam that he wasn’t part of the church any longer, but that writing—one might say human creativity—was his religion.

It had replaced the church and all the church entailed. This dissatisfaction with the church, with all its shortcomings and harmful ways, was present even before he claimed writing. In his words:

And the blood of the Lamb had not cleansed me in any way whatever. I was just as black as I had been the day that I was born. Therefore, when I faced a congregation, it began to take all the strength I had not to stammer, not to curse, not to tell them to throw away their Bibles and get off their knees and go home and organize, for example, a rent strike.

This type of turn from Christianity in particular and theism in general is also a component of the Black Arts Movement, with figures like LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka, 1934–2014) who raised questions concerning the existence of God. The Black Church and other forms of Black theism offered nothing that they found compelling, that explained or challenged the suffering that marked Black life in the United States.

Drawing on the energy and aesthetics of Black Power, these artists in literature, visual expression, and performance explored the dynamics of life in terms of its materiality in the here and now. They gave no credence to prospects of another world, or spiritual renewal. They were content to limit themselves to an expression of the joys and pains of life as Blacks encounter it.

In other words, these artists didn’t look beyond this world for motivation or guidance; they pored through the stuff of the world—the dance, the singing, the clothing, the jokes, the foods, the warmth of community—for the values that should rightly guide them and other Black people. For these advocates of Black life’s complexity and richness over against the toxic qualities of white supremacy, a humanity-inclined approach to life afforded mental freedom and creativity, if nothing more.

______________________________

Excerpted from The Black Practice of Disbelief by Anthony B. Pinn. Copyright 2024. Excerpted with permission from Beacon Press.

Anthony B. Pinn

Anthony B. Pinn is the Agnes Cullen Arnold Distinguished Professor of Humanities and professor of religion at Rice University. He is also the founding director of Rice's Center for Engaged Research and Collaborative Learning. Pinn is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and Professor Extraordinarius at the University of South Africa. In addition, he is Director of Research for the Institute for Humanist Studies. Pinn is the author/editor of numerous books, including Interplay of Things: Religion, Art, and Presence Together (2021) and The Black Practice of Disbelief: An Introduction to the Principles, History, and Communities of Black Nonbelievers (2024).