Repetition Ruins a Narrative: On Trying to Create Amid the Sameness of Pandemic Parenting

Rosalie Knecht Considers the Narrative Machines That Power Fiction and Therapy

Recently, I’ve lost the ability to think narratively. Library books languish and are returned unread. My own fiction projects are multiplying but not going anywhere, generating outlines I will never use. When I read fiction, I find myself thinking, “Why are you telling me this made-up story?” Narrative feels like a cheap trick.

This is a real problem for me, professionally and personally, and I was thinking about it one night a couple of weeks ago while washing dishes and hoping that my son, who had pneumonia, would be able to sleep without waking himself up over and over with wracking coughs. He and his baby sister have been sick almost constantly since November. They got respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which was brutal for both of them and put the baby in the hospital.

Then, less than a month later, they both got COVID. Then they both got metapneumovirus (kind of a B side respiratory virus, similar to RSV). Then they both got a stomach virus, which also felled my husband and me. Then my son got pneumonia secondary to a cold of some kind, and while he was recovering, the baby got pinkeye, and while the baby was getting over that, my son got another new bug, with two or three days of high fever, and then, when he was well enough to go back to daycare, the baby got another upper respiratory infection, and my husband wearily got out the albuterol and unpacked the nebulizer machine that we had briefly put away in a closet.

This is a partial list. These are just the illnesses that were severe enough that we saw a doctor and got a diagnosis, plus the three that happened since I started trying to write this essay. (Which is supposed to be about therapy in fiction, by the way. With some luck, I may get there.)

We had packed up the nebulizer because we thought we had to be coming to the end of all this. We were about to get a break, for sure. Cold and flu season is over now, right? It’s June.

But it hasn’t stopped. It hasn’t even slowed down. This is partly a pattern all parents know—kids in daycare bring home germs. Their immune systems aren’t fully developed yet, and they get sick much more often than adults. But it’s also an effect of the pandemic. I’ve started asking my kids’ doctors—obvious desperation in my exhausted face—if this is normal, or if it’s just us. And they keep telling me the same thing: the pandemic has stretched out virus season. The isolation and masking of the first year limited exposure to routine viruses, which lay in wait and then came roaring back. So cold and flu season goes on and on. And of course, inseparably, the pandemic goes on and on.

Repetition ruins a narrative. That’s what finally clicked for me while I washed dishes and listened to the coughing coming from the room at the end of the hallway a couple of weeks ago. What have the last two years been but a brutal and disorienting round of repetitions? How can I talk about something that’s always the same? I’ll bore you. Narratives are what we put together so as not to bore each other. The COVID surges come in waves, not arcs. My kids’ ailments form a stupefying, meaningless stutter. We’re about to get back to normal, and then we aren’t, and then we’re about to, and then we aren’t, again.

When I got sick as a kid, my mother liked to read to me from a book called The Plague and I by Betty MacDonald. The book is a memoir, published in 1948, about the writer’s nine months in a sanatorium with tuberculosis. It’s a comedy.

The sanatorium was called The Pines. It was huge, always cold, and managed by a medical team of implacable monsters. Patients were forbidden for months at a time from speaking, laughing, sitting up in bed, reading, or writing. They couldn’t have visitors at first, for fear that seeing their families would overexcite them and make them tear the delicate healing tissues in their ravaged lungs.

They lay perfectly still in bed, day after day, staring at the ceiling, feeling the damp breeze from perpetually open windows (open in part to protect the staff from becoming infected—they understood aerosols even then). Many patients spent years there. Imagine hearing this as an eight- or nine-year-old child going out of her mind with boredom and discomfort after a couple of days at home with the flu. A more vivid hell had never been described for me, unless you count the third chapter of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and honestly if I were given a choice between the two, I might pick the lake of fire. At least there would be something to look at.

What have the last two years been but a brutal and disorienting round of repetitions? How can I talk about something that’s always the same?

In March 2020, I thought a lot about The Pines. What was there to look at in March 2020? There was my son, whose first birthday came shortly after the shutdown. And there were my therapy clients, appearing self-consciously on screens for the first time. I looked forward to seeing them each week, hearing what they had been thinking, noticing the figurines and photos behind them. I commented on any change in backdrop as if it were a new haircut. My clients stepped out of frame to pour tea and came back. Their pets interrupted.

Despite being a writer, I’m an extrovert, and this amount of contact with people outside my household, constrained as it was, meant a lot. I recalled the passages in The Plague and I where MacDonald recounts conversations among the patients on her wing, the excited dissection of the minutiae that could change. Who brought the dinner trays? Who had been moved from the inside wards out to the porch? Which nurse was running the baths this week? Who had had surgery? They tried so hard to make stories out of days that were all the same.

In March 2020 I was also working on a novel, the third in a series. For the first few months we spent indoors, I worked out fantasies on the page—scenes of house parties, camping weekends, long drives. Imagine travel! Imagine friends! Eventually, the needs of the plot interrupted the revelry, and my protagonist found herself in a psychiatric institution, looking for allies among patients depleted by repetition and confinement. She sat, grudgingly, in a group therapy session.

Narrative is essential to the art of therapy. We have well-worn narratives about our own lives, how we came to be who we are, what the world is like. All narratives are false. The question isn’t whether the narrative you have about your life is accurate or inaccurate; it’s too simple to be accurate. The question is whether it’s working for you or not.

A narrative is a little machine. It takes the chaos of incident that makes up your real life and spits out something you can hold easily in your mind. Is your narrative doing a good job? Is it letting you get out of bed and do the things you need to do today? You make a plot by leaving things out. I think I learned that from Terry Eagleton. Are you leaving the right things out? At the moment, I can’t make my machines work at all. I can’t make the one I tell myself about myself work, and I can’t make the fake ones work either. The falseness feels deadening instead of generative.

The question isn’t whether the narrative you have about your life is accurate or inaccurate; it’s too simple to be accurate. The question is whether it’s working for you or not.

I can’t resist writing therapy scenes into my fiction because in therapy, characters are goaded into telling the story themselves, grabbing the wheel from the narrator. Sometimes they do it well and sometimes they do it badly. Sometimes the therapists are good, and sometimes, maybe more often, they are bad. The holes in a story a person tells about herself, the weaknesses of an obtuse therapist—the failures are what interest me. The failures—the absences—are what delineate the shape of the arc.

I’ve been working on this essay for weeks now. I’ve started and stopped many times. I’ve written four different openings, three middles, zero ends. When I started, my son was coughing in the other room. Now my daughter is coughing at the far end of the apartment. It’s June, but it could just as easily be December or March, if not for the breeze coming through the open windows. I don’t know what it means. We are exhausted, but is it serious? We’re not sure. It could be so much worse. So many others have had it so much worse. Anyway, I tried to make something tidy out of the chaos. I failed (we always do).

________________________________

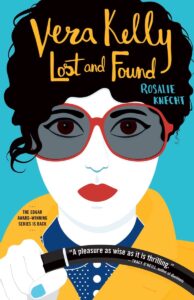

Vera Kelly Lost and Found by Rosalie Knecht is available now via Tin House.

Rosalie Knecht

Rosalie Knecht is the author of Who is Vera Kelly?, Vera Kelly is not a Mystery, winner of the Edgar Award, G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award and a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award, as well as a Relief Map, and a translation of Aira’s The Seamstress and the Wind. Vera Kelly Lost and Found is her latest novel. She lives in Jersey City, NJ.