Remembering the Moments Before the Charlie Hebdo Attack

Survivor Philippe Lançon on Memory and Fate in the Wake of Violence

It was 11:25 in the morning, perhaps 11:28. Time disappears just when I would like to recall it down to the second, like a tapestry woven by a Fate named Penelope, the whole of which depends on the slightest point. Everything is connected, but everything falls apart.

I got up and put on my pea coat. It was time to go back to Libération to write about Twelfth Night, but first about Blue Note, the big book on jazz that I’d put in the knapsack that I’d brought back from Medellin, in Colombia, five years earlier. It was a little bag in black fabric, very light, on which caricatures of national celebrities were reproduced. I was seldom without it. It has disappeared.

This bag had been given me by the writer Héctor Abad, the author of a book on the life and death of his father and the tragic history of his country, El Olvido que seremos (Oblivion: A Memoir). We were in the used bookstore that he had founded over there along with a few friends. I have learned that since then it has moved, for lack of money. I’ve always loved little bookstores where used books invade everything, to the point of seeming to take the place of air. They are cabins in the depth of cities, in the depth of the woods. It seems to me that nothing bad could happen there: a labyrinth without fear or danger. This was a small one called Palinurus.

Palinurus was Aeneas’s helmsman. Apollo makes him fall asleep as he is guiding the ship through the night. Falling into the sea along with part of his steering oar, he washes up on land and is killed by savages. His shade wanders through the underworld, where Aeneas meets him again. He had believed that his helmsman simply drowned. Palinurus’s shade tells him how he really died.

One has to rejoin the dead to learn how far they have gone, but on that day, at 11:25, perhaps 11:28, with my bag in black fabric on my shoulder, I still didn’t know that. Neptune had promised Venus that Aeneas and his men would arrive unharmed at the port of Avernus, but this immunity came at a price: “One shall be lost, / but only one to look for, lost at sea: / One life given for many.”

Héctor Abad’s father, a militant democrat, was assassinated by paramilitary killers on a sidewalk in Medellin in 1987. His son got there almost immediately. In a pocket of his father’s suit, he found a poem attributed to Borges, which begins with this verse, from which his book takes its title: “We are already the oblivion we shall be.” That is the talisman and last trace, the last mystery of the dead man. Since it is not to be found among Borges’s works, its authenticity has been contested.

Hector seeks, from one end of the world to the other, its uncertain origin. His quest is the subject of a second book, Traiciones de la memoria (Treasons of Memory). Determining whether it is a counterfeit becomes an essential question. That is the message that his father has left him, in spite of himself. The investigation into the traces of a life suddenly interrupted is what remains when death has carried off those whom we miss and what leaves us, in a way, alone in the world.

An investigator of this kind is often criticized for his obsession, because one cannot, after all, criticize him for his sadness and distress—at least, not immediately. Those who are not obsessed, those who move on to other things, the elegant and the indifferent people, do not belong to the world in which he has to live. There are, of course, many ways of revising, over and over, the account of one’s own sorrows. But just as at school, once the composition has been turned in, not everyone has an eraser to efface what has taken place.

This little bag always reminded me of Hector, his book, his father’s death, the life and death of the drug trafficker Pablo Escobar, Borges’s poems, and the beauty of Medellin’s valley. With him, I always felt here and elsewhere, open to all humanity, and I had the feeling that I could return at any time to Colombia, that country where the worst things had been done amid the most extreme beauty. I was about to leave when, seeing Cabu, I took out the book on jazz to show it to him, to show him above all a photo of the drummer Elvin Jones.

In 2004, after I learned of Jones’s death, I wrote a column about him in Charlie. Cabu remembered the circumstances under which he saw the drummer, outside, at the Châteauvallon Festival. He told me about it and I put his memory in my column: “Suddenly, the thunderstorm breaks out. It is violent. The musicians and most of the audience, everybody gradually disappears, as everyone disappears in La Symphony des Adieux; everybody, except Jones.

Wild, excessive, beating the time from beyond the tomb, this giant with steel hands gives life to the drumheads and cymbals amid the lightning bolts, alone like a forgotten god, an Asian god with countless arms. The storm seems to have been created by him, for him. He merges with it. He’s 50 years old, the thunder remains.” That was in 1977. Twenty-seven years later, Cabu made a drawing of it that, juxtaposed with my column, gave the latter a value it does not have, or at least would not have without the drawing. Being “illustrated” by Cabu, particularly regarding jazz, or rather accompanying one of his drawings in writing, took me back to a happy adolescence, the one I discovered along with Céline, Cavanna, Coltrane, and Cabu. It was rather as if, writing in 1905 a novel that took place in the world of dancers, the book’s illustrations were by Degas.

When one doesn’t expect it, how long does it take to sense that death is coming? It’s not only the imagination that is overwhelmed; it’s sensations themselves.

If Elvin Jones had not died, I wouldn’t have written that column. If I hadn’t written the column, Cabu wouldn’t have made that drawing. If Cabu hadn’t made that drawing, I wouldn’t have stopped that morning to show him the book on jazz that had reminded me of it. If I hadn’t stopped to show it to him, I would have left two minutes earlier and I would have run into the two killers in the entrance or on the stairway, I’ve recalculated that over and over. They would no doubt have put one or several bullets in my head and I would have joined the other Palinuruses, my companions, on the shore with the savages and in the only hell that exists: the one where one is no longer alive.

I put the jazz book on the conference table and said to Cabu: “Here, I wanted to show you something . . . ” It took me a little time to find the photo I was looking for. Since I was in a hurry, I thought that I should have marked the page; but how could I have done that, since I didn’t know, one minute earlier, that I was going to show it to him? I didn’t know if he would be there that day—even though he rarely missed the Wednesday meeting: Cabu had drawn countless dunces, but he was no truant.

The photo of Elvin Jones dates from 1964 and covers pages 152–153. He’s lighting a cigarette with his right hand, which is simultaneously enormous and delicate, and holds two crossed drumsticks. It’s a close-up. He’s wearing an elegant, finely checked shirt, slightly open at the neck. The sleeves are not rolled up. His eyes closed, he draws on the cigarette. Half of his face, powerful and angular, is framed in the upper triangle of the two drumsticks, as in the forms of a cubist painting. The photo was taken during a recording session for Wayne Shorter’s disc, Night Dreamer.

Cabu found it as beautiful as I did. I was happy to show it to him. Jazz was, ultimately, what brought me closest to him. As for the book, he knew it already. We leafed through it and I closed it when Bernard, coming up to me, said, “Don’t you want to write your column on Houellebecq?” I was responsive to his enthusiasm, which was always announced by a broad, benevolent smile, to the peculiar candor, not without cunning, that arose from his bursts of fellow feeling and perpetual curiosity, but I replied, more or less, “Definitely not! I’ve just written in Libération what I thought of him, and I’ve no desire to suck that tit again.”

From the other end of the table, Charb said: “Oh, please, suck that tit again for us . . . ” There were a few smiles, and it was at that moment that a sharp sound like a firecracker and the first screams in the hallway interrupted the flow of our jokes and our lives. I didn’t have time to put the jazz book in my little black bag. I didn’t even have time to think about it, and then everything ordinary disappeared.

When one doesn’t expect it, how long does it take to sense that death is coming? It’s not only the imagination that is overwhelmed; it’s sensations themselves. I heard other little sharp sounds, not at all the noisy detonations in movies, no, dull firecrackers without reverberations, and for a moment I thought . . . but what did I think, exactly? If I wrote something like: for a moment I thought we had unexpected visitors, perhaps undesirable ones, even absolutely undesirable, I would immediately want to correct it in accord with a grammar that no longer exists. I would bring together all these clauses and, at the same time, distance them enough so that they no longer belonged either to the same sentence, the same page, the same book, or the same world.

Like the others, I had probably already slipped into a universe in which everything happens in a form so violent that it is thereby attenuated, slowed down, as it were, consciousness no longer having any way of perceiving the instant that destroys it. I also thought, I don’t know why, that it might be kids, but “thought” isn’t the right word, it was merely a succession of little visions that immediately evaporated. I heard a woman cry, “But what . . . ,” another woman’s voice scream, “Ah!,” and still another voice shout in rage, more stridently, more aggressively, a kind of “Aaaaah,” but I can identify that voice, it was Elsa Cayat’s.

For me her cry meant simply: “Who the hell are these asshooooles?” The last syllable stretched from one room to the other. In it there was as much rage as fear, but there was still a great deal of freedom. Perhaps that was the only moment in my life when that word, freedom, was more than a word: it was a sensation.

I still thought that what had taken place was a practical joke, though I already sensed that it wasn’t one, but without knowing what it was. Like lines on tracing paper inexactly superimposed on a drawing that has already been copied, the lines of ordinary life (of what in ordinary life would represent a farce or, because this was the place for it, a caricature) no longer corresponded to the unknown lines that came to replace them. We were suddenly little figures imprisoned within the drawing. But who was doing the drawing?

The irruption of naked violence isolates a person from the world and it isolates others from the person who is subjected to it. In any case, it isolated me. At the same moment, Sigolène’s eyes met Charb’s and she saw that he had understood. That is not surprising: Charb had few illusions regarding what people are capable of, he was never dramatic, never pompous, and that is also why he was often so amusing. He undoubtedly did not need the few seconds of life that remained to him to comprehend what kind of pathetic comic strip these two empty, hooded heads bearing bigotry and death came from, to see them as they were before they disfigured him.

Already, I no longer saw anything or anybody except, across from me, with his back to the entrance at the other end of the little room, the silent Franck, Charb’s bodyguard. He was there because it was his job and, it seemed, his habit. Threats destroy the ordinary perception of life only when they have been fixed by acts. Similarly, bodyguards seem useless, except as ghostly, benevolent escorts, until the day when one would have preferred to see them be good for something, indeed for everything.

I saw Franck stand up, turn his head and then his body toward the door on the right, and it was then, observing his actions, seeing him in profile drawing his gun and looking toward that door opening on something unknown, that I understood that this was not a joke, or kids, or even an aggression, but something entirely different.

_____________________________________

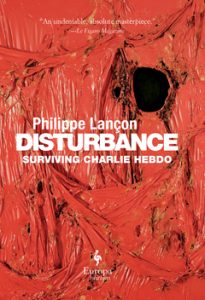

From Disturbance: Surviving Charlie Hebdo. Used with permission of Europa Editions. Translated by Steven Rendall. Copyright © Editions Gallimard, Paris 2018. Translation copyright © 2019 by Europa Editions.

Philippe Lançon

Philippe Lançon is a French journalist and writer born in 1963. His memoir, Disturbance, won the 2018 Prix Femina, Prix du Roman News, and Prix Renaudot Jury’s Special Prize, and was also named Best Book of the Year by the magazines Lire and Les Inrockuptibles. He is the author of the novels L’Élan (2013) and Les îles (2011).