Remembering My Father Through My Favorite Beatles’ Song

Elissa Schappell is Always Happy to Revisit the Octopus’s Garden

When I was a little girl my family used to sing Beatles songs on car trips. It sounds impossibly quaint now, but it was the 1970s and my family—mother, father, sister, and me—just the four of us—sailing down the highway in our station wagon, singing—well, we were happy.

Ringo was my favorite Beatle, so I loved to sing “Yellow Submarine” and “Octopus’s Garden,” and it is Ringo who begins the story of the Yellow Submarine.

“In the town where I was born, lived a man . . .”

This was my father’s part. Sometimes it was necessary to cajole my parents into singing; other times my father would just begin, the three of us joining in—and finally the Beatles came in for the chorus. For all I knew (and I hoped I was right), somewhere on the other side of the world people were already actually living in yellow submarines. It was trippy, but entirely possible.

It was our song.

After we finished singing “Yellow Submarine,” we’d segue into “Octopus’s Garden”—

“I’d like to be under the sea . . .”

—but honestly, there wasn’t the same level of enthusiasm. Maybe because my dad didn’t begin it? Maybe because it wasn’t about the joys of living underwater with your friends and family and being happy forever, but about freedom? About being able to escape your ordinary life and run away to a place where no one could tell you what to do.

This was what made it feel like my song.

“Octopus’s Garden” required the same sort of leap into fantasy, although I wouldn’t have called it fantasy, but the realm of possibility. It was entirely possible that, if you were the right kind of person—polite, brave, and well mannered—you could make friends with an octopus. Surely if you did, the octopus—who in cartoon form is often depicted wearing a top hat and ascot, and occasionally a monocle—would invite you and your friend into his home. Octopuses are known to be house-proud. And surely if anyone could befriend a cephalopod it would be Ringo. And if Ringo were to take anyone, why not me?

*

“Yellow Submarine” and “Octopus’s Garden” are admittedly not the best Beatles songs, but they are emblematic of a time in my childhood when the depth of my misery was being forced to pull weeds, cut grass, and rake leaves.

Later, I’d graduate to Keith Moon; there was something exhilarating and terrifying and sexy about Moon, who refused to be relegated to back of the band, but rushed, as though ravenous, to meet the drums. He wasn’t simply playing them. It was like they had come alive. Watching Moon in the throes of a jaw-dropping solo, wild-eyed and wet with sweat, his sticks a blur as he works himself into a hedonistic frenzy—he might as well be at an orgy.

But this is the opposite of what I wanted as a girl. What I wanted was to be filled up with music that made me want to dance around my parents’ basement and, at the very top of my lungs, sing songs about hiding out with an octopus in a coral-protected cave. I wanted magic.

That age and those times spent listening to my parents’ Beatles records in our basement, believing it was a place bad fortune could never find us, are among the happiest of my life.

*

I liked Ringo not only because he wasn’t the most popular Beatle (early instance of my lifelong suspicion of whatever is most popular), but because he was the drummer (early indicator of my lifelong thing for drummers). Ringo was the devilish, happy prankster with the saucer-sized eyes. Beyond his role as drummer, sitting at the back of the band, yet holding everything down, Ringo always seemed slightly on the outside, a part of something, but alone, wisecracking in the background.

Still, from the way Ringo was always laughing and clowning around, you’d never have guessed he was unhappy. Of course, later we’d hear he’d been miserable. Maybe, in that way, I recognized myself in Ringo.

*

It wasn’t until I was older that I learned people could change their names. That Ringo Starr’s given name was the far less glamorous Richard Starkey, or that the nickname “Ringo” came from his taste for flashy rings, and “Starr” was because his Beatle brothers called his drum solos—such as they were—“Starr-time.”

*

The first time my father was diagnosed with cancer I was 15 and it was lymphoma. A tumor the size of a small grape growing in the lymph nodes beneath his jaw. The second time I was 22 and it was a tumor the size of an almond in his left lung.

In order to remove the diseased part of his lung, they had to crack his rib cage.

In the sun, the large C-shaped scar on his back turned white.

After his recovery, my father—who had several times taken the family snorkeling, pointing out spiny black urchins and starfish in Jamaica, barracudas and clown fish in the Yucatán; who was always, it seemed, rescuing me or my little sister from being dashed against the reef—announced he was taking up scuba diving.

It is true that starfish can regrow lost limbs. Not only that, if the severed limb contains enough of the main body, it can regenerate. It can become a totally new starfish.

*

It makes sense that Ringo would find a muse in the octopus. In undersea cartoon bands the octopus is always the quirky drummer. Who could resist?

One arm for the bass drum, another for the snare and hi-hat, one for a tom.

If you consider the octopus’s decentralized nervous system and the fact that more than half of its neurons are located in its arms—thus its astonishing dexterity—if any creature in the kingdom could play the drums, it would be the octopus.

There is no evidence that the octopus can regrow a lost limb.

Although the octopus is almost always depicted as being goofy—it’s all those silly arm-legs and the balloon shape that seems to call out for a loopy grin—to me, the octopus looks haunted and inscrutable. The octopus—despite depictions of him as a goggle-eyed roller-skating spastic, a bumbling tap dancer with eight left feet—never seemed all that comical to me, even as a girl. People thought he was ridiculous because of the way he looked and so they made him ridiculous.

Make the octopus ridiculous; go ahead—so much the better. For the octopus wants nothing more than to be left alone. In captivity they are notoriously difficult and cunning. At every turn they defy their captors—be they researchers or zookeepers. Taken from their homes, they sulk, refuse to run mazes, and seemingly enjoy employing those remarkably dexterous arms to sabotage plumbing and electrical wiring.

Should they wish to elude you, they will change the color and texture of their skin. Hoping to pass for a bit of seabed when a shark slips by, they camouflage themselves by turning a pebbly mottled green. Should they be struck by desire, they will slip into something more comfortable, perhaps a skin of velvet plum and gray.

Even the octopus’s most famous trait—the ability to shoot a cloud of ink (actually melanin, the pigment respon- sible for coloring human skin) into the face of a predator—jibes with Ringo’s sense of humor.

*

The story is that Ringo was inspired to write “Octopus’s Garden” while sailing in Sardinia, when the ship’s captain told him of the octopus’s fondness for decorating its lair with rocks, shells, bits of sea glass, and anything else that caught its fancy. Ringo was smitten.

From that time forward Ringo never again ate octopus.

As a girl, I was inspired to draw octopuses in their undersea gardens. I decorated their lairs with checkered curtains and candelabras. I also often confused the words tentacle and testicle, which provided my parents with great amusement despite the fact that no creature, even the despised mongoose, deserves to be burdened with eight testicles.

I stopped eating octopus when I watched one open a jar on YouTube.

*

Growing up smaller than most kids, with a sister who was smaller still, I was ever on the alert for a wave of teasing. I quickly developed a pointed wit, scarcely more harmful than a joke-shop daisy that shoots water—still, I could depend on it to at least momentarily distract my attacker, allowing me to escape.

*

I wasn’t good at sports. Except for gymnastics. My parents, wanting to encourage me in the one sport I excelled at, set up tumbling mats and a balance beam my father had built for me, in the basement.

Our basement wasn’t like a lot of my friends’ basements. There was no shag carpeting or wood paneling, no pool or foosball table, and surely no TV. The concrete floors were painted bluish-gray, the back wall was exposed concrete, there was a narrow crawl space where we kept the sleds and Christmas tree stand, there was a washing machine and dryer, and overhead a network of copper pipes snaked along the low ceiling. It was cool and smelled like earth. Even so, it was a magical place to me as a girl. It was warm in the winter and cool in the summer. One could imagine, with the sound of the washing machine and footsteps overhead, that one was indeed in a cave beneath the waves.

Every night after dinner, unless there was still daylight, in which my father might go outside and walk around his yard surveying the plantings and flower beds, he would head down into the basement, and my sister and I, if our homework was done, would follow him.

My sister and I liked to play records and do gymnastics while my father welded. With mask in place and acetylene torch in hand, sparks flying around his head, our father transformed metal rods into people—a mother with two daughters—a Big Bang explosion of geometric shapes that would hang over our hearth, a life-sized man with curly hair and uncircumcised penis that brought us no small measure of embarrassment when friends came over, and fish swimming through coral. One fish, which was five feet long, commissioned by a couple whose property backed up to the woods, looked like it was swimming through the trees.

Running along the wall over my father’s workbench was a pegboard hung with tools: silver wrenches whose jaws opened with the spin of a dial, screwdrivers with clear-yellow-and-black-striped handles; toothy handsaws, for trimming branches and cutting wood; and hammers—claw hammers and small hammers, and one with a rubber tip. At the very top, in the shadows up near the ceiling, was a dusty model ship my father had built in high school, a gold-and-green-painted schooner with real rigging and sails. It was a wonder. There were pieces of graph paper outlining his landscaping plans, trying to imagine where to put this rhododendron and that azalea.

No matter how many hundreds of times I poked around my father’s workbench I always discovered something new. A silver can that turned cold when you shook it, a clear box containing all the rattlesnake rattles he’d collected throughout his life growing up in the Pennsylvania woods, ball bearing marbles, and a blue birdcage my father had carved—not five inches tall, with a yellow bird inside. The cage had no door. How could my father, even with the slimmest blade, have carved the bird inside that cage?

Every night my sister and I would practice. “Daddy!” we’d call out, standing on our heads. “Watch me! Watch this!” we’d shriek as we wobbled along the beam. “Want to see what I can do?” we’d yell, trying to jump up to grab ahold of one of the low-hanging pipes and do a chin-up. “Look, do you see? Are you looking?”

And my father would, very good-naturedly, always put down whatever he was doing and come over to watch us, spot my back handspring, admire our cartwheels, clap even when we slipped off the beam. Look at how strong you are, he’d say. Wow, you are really getting it. And he’d shake his head in appreciation and wonder like he couldn’t even imagine doing a forward roll.

We played Abbey Road all the time. Even so, every time the song began—there was that melodic little burp of bubbles before Ringo began to sing—my sister and I would go wild, bellowing joyfully at the top of our lungs (after all, there was no one except for our father to hear us), “We would be so happy, you and me!”

This was the time when we believed my father could do magic.

We would still believe it, my mother, my sister, and I, when my father discovered the first tumor, and we would believe it until the day he died, fourteen years and two seven-year stays of remission later. For a time, I believed he might even come back. Was that a fantasy? Was that completely beyond the realm of possibility?

*

My father spent the majority of his waking weekend hours out working in the yard. Long before we’d awake he’d have cranked up the rock and roll—Rolling Stones, Beatles, Grateful Dead—and be outside pruning trees, planting bushes, perhaps weeding the flower bed, although that job fell mostly to me and my sister.

I could never understand what pleasure my father got from working in the yard. It was so hot and buggy and tedious. It was unfair that I was not allowed to weed the grass in my bikini, or operate the chain saw.

I did, however, love our yard. Behind our house were woods—walnut and poplar trees—and, in front of a split-rail fence, a long bed of overflowing flowers and painted grasses, and swaying stalks of freckled yellow, pink, and purple foxgloves who opened their mouths like dragons when we pressed the sides of the flower. Magenta coneflowers sprang up straight, and silvery lamb’s ears laid low. There were violets, and pink and white bleeding hearts spread out of the beds, finding their way into the woods behind our house, with the bright-orange-and-black-streaked tiger lilies, and my favorite of all—the fragrant, frilly, pink and white and red, nearly purple, peonies. My father let me cut the blooms to take to school (despite the ants sequestered between the petals), their stems wrapped in wet paper towel and tin-foil, so I could smell them all day even as I flicked ants off my desk.

In the beds beside the house grew grandiflora magnolias almost as tall as our house, with dark green leaves and enormous, fragrant cream-colored blossoms bigger than your outstretched hand, and petals soft like skin. The hill was banked with coral and pink primroses, blue-and-green-and-white-striped hostas mingling with lily of the valley and spreads of feathery ferns. In front of the house, under the walnut and dogwood trees, appeared trillium and the otherworldly-looking jack-in-the-pulpits. Behind the house, flanking the woods, were two decorative ponds full of koi, peepers, a snake or two, and occasionally, haunting the greenery, rabbits and a box turtle.

It was its own world.

*

The last time I’d see my father at home, his cancer had metastasized from his lungs to his spine. The chemotherapy doubled him over with nausea. The cold of the bathroom tile made his feet cramp; it was painful for him to walk. He was, despite his best efforts, often irritable.

Even so, I asked him if he’d walk around the yard with me, and talk to me about the garden. I asked if I could film him. Yes, it felt artificial. No, I didn’t know it would be the last time I’d walk around the yard with my father, or the last time he would walk through his garden.

The feeling my father said he had been going for was an English garden. “Listen,” he said, “the most important thing is to do what you want to do . . .” He paused to rub his aching lower back where the cancer had begun to climb his spine. “I, personally, like the look of an English garden, but that’s me. The important thing is to plant a garden you want to spend time in. You. No one else.”

That spring he’d said that everything in the garden was the most beautiful it had ever been. Even the bark on the trees, he said. His peonies were glorious. Then there were the lightning bugs, which he said he thought were the greatest things in the world. And we’d stood on the deck at dusk with night coming on, watching for those pops of vivid green light burning like signal fires.

The night my father died, a white water lily bloomed in the bottom pond. Even in the moment it felt trite. That night, for the first time unafraid of the dark, I walked down to the edge of the yard and lay in the wet grass, stretching out by the flower bed. I put my hand in the dirt and let it fall through my fingers, thinking I wanted to be somewhere my father had put his hands.

*

The last time I went home before my mother sold the house and moved, I walked around the yard as I had so many times before, in the daytime in the afternoon, in the dark. I rebuilt the stone wall that ran along the driveway. Shovel in hand, I roamed the property digging up plants—ferns and hostas—that would do well in the shade and a peony that wouldn’t. I took a dogwood sapling and two pairs of jack-in-the-pulpits and weeds. I dug up my father’s weeds, clover, and crabgrass, and transplanted them into my own garden. Tomorrow, my father will have been dead for 20 years. I intend to work outside as I always do on this day to honor him. I will water and dig and listen to his favorite music, the music he loved best—the Rolling Stones, Neil Young, the Grateful Dead, and yes, of course, the Beatles. Especially the Beatles, so I can, if only for the time it takes to sing “Octopus’s Garden,” be that girl. The one who could easily imagine a world where an octopus would take you in and give you tea, where you could sing and dance around in your basement with your father forever, the one who couldn’t yet understand how sometimes you cried over a song because it made you both happy and sad.

__________________________________

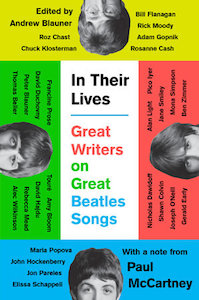

From In Their Lives: Great Writers on Great Beatles Songs edited by Andrew Blauner. Used with permission of Blue Rider Press. Copyright 2017 by Elissa Schappell.

Elissa Schappell

Elissa Schappell is the author of Use Me, a finalist for the PEN Hemingway award and Blueprints for Building Better Girls. She is a Contributing Editor at Vanity Fair, a former Senior Editor of the Paris Review, and a co-founder and former Editor-at-Large of Tin House. She lives in upstate New York.