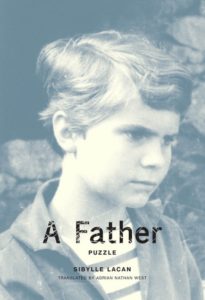

Remembering My Father, Jacques Lacan

Sibylle Lacan on the Influences of an Absent Father

When I was born, my father was already no longer there. I could even say that when I was conceived, he was already elsewhere, he no longer really lived with my mother. A meeting in the country between husband and wife, after everything was already over, marks the origin of my birth. I am the fruit of despair; some will say of desire, but I do not believe them.

Why then do I feel the need to speak of my father now, when it is my mother whom I loved and continue to love after her death, after their deaths?

Affirmation of my heritage, snobbery—I am the daughter of Lacan—or a vindication of the Blondin- Lacan clan against the Bataille-Millers?

Whichever it may be, my sister, now gone, my older brother, and I are the only ones who bear the name Lacan. And that is what this is all about.

In my memory, I didn’t know my father until after the war (I was born at the end of 1940). I don’t know if this is really true, I never questioned Maman about the subject. Probably he used to “pass through” now and then. But in my reality, there was Maman, and that was all. Not that anything was missing; things had never been otherwise. We knew we had a father, but apparently a father was something that wasn’t there. For us, Maman was everything: love, security, authority.

An image of the period remains fixed in my memory, as though frozen in a photograph: my father’s silhouette in the doorway, one Thursday when he’d come to see us: immense, swathed in a vast overcoat, there he was, looking burdened by who knows what worry. A custom was established: he would come to Rue Jadin once a week for lunch.

He spoke formally to my mother and addressed her as “my dear.” Maman, when she spoke of him, called him “Lacan.”

She had advised us, at the beginning of the school year, when we had to fill out the ritual questionnaire, to write the word “Doctor” in the blank asking for father’s profession. In those days, psychoanalysis was seen as little more than charlatanism.

*

It was on the island of Noirmoutier, where we would regularly spend our long vacation, that “the abnormal” glided into our lives. Our young, well-intentioned friends revealed to us that our parents were divorced and that, and as a result, Maman would be sent to hell(!) I don’t know which of these two disclosures hit me harder. At naptime, my brother and I held a long consultation.

*

Why then do I feel the need to speak of my father now, when it is my mother whom I loved and continue to love after her death, after their deaths?

The years continued to unwind. Maman played every role. We were “handsome,” intelligent, and worked hard in class. She was proud of us, but she wanted us to grow up. After the war, that was her obsession: guiding the three of us into adulthood.

Papa, for our birthdays, would give us superb gifts (I believe it took me far too long to understand that he was not the one who picked them out).

*

In a timeless time, in an indeterminate space—though I did learn from my brother, some years back, that it was not something I merely dreamt—an extraordinary event took place. Childhood, Brittany, Thibaut, my father, and I. What were we doing there with my father? Where was my mother? Why was Caroline— in my recollection—not there? The three of us were visiting a castle. Thibaut was racing down the spiral stairway of a tower. Where am I, exactly, with respect to him? And my father? But I see this: at a bend, to the right, is an opening that gives directly onto the emptiness, a door without a ledge or parapet. Thibaut, in his boyish eagerness, barrels toward it. My father catches him by his clothes. A miracle!

Second scene: we rejoin Maman and I tell her, upset, how Thibaut has skirted death. No shouting, no weeping, no apparent emotion. I do not understand. I have never understood. My brother has retained no tragic memory of this event. My father never spoke of it again. Maman, who did not react at the time, never again brought up the disaster we had only just avoided.

Formentera is the name of the island I have chosen as a second home, as a vacation home: fort m’enterra. (“Fort/the strong one buried me.”)

And if a father was good for anything, it was that: to administer justice.

*

The law of primogeniture governed life at home. In this way, Maman reproduced what she had experienced in childhood—she was, like me, the youngest—and what she considered “normal,” inevitable, in other words: just the way things were. Above us all was Caroline, four years older than I (though the distance seemed far greater). She held all the power… and all the privileges. She became a woman very early on, tall, with long, thick hair of a blond color unusual in our region, flourishing like a Renoir (I was always the smallest in my class, a blend of femininity and failed boyishness), beautiful in the eyes of all (I was only ever “cute”), remarkably gifted and intelligent (first prize all her life, head of the class, a brilliant university career—I was a good student, but always had to work for it); in a word, a goddess incarnate, she lived in a world apart, closer to that of Maman than to ours. By “ours” I mean my brother’s and mine, who were, throughout our entire childhood, “the little ones.” And yet, there was still another subdivision in force: Thibaut was not only a year older than I, but also a boy—an incontestable advantage in the eyes of Maman, despite her professed ideas about the equality of the sexes. And so it was natural that he not make his bed, that he not set the table, and other “details” that clashed profoundly with my sense of justice.

If it happened that my brother and I joined forces against my sister, who did not hesitate, in the most extreme cases, to defend her privileges with force, the result, most often—the general character of these occasions, if I may put it this way—was the exposure of my own inferiority. I was described—of course, it was only a “wisecrack,” and even Maman laughed along—as “dumb, ugly, and nasty.” Another of their mottos was “Sibylle is anything but a thief”(!) Naturally all that might have been funny had the “victim” not always been the same, or if the occasional compliment, or some gesture of tenderness, had sometimes come afterward, to compensate for that mania for belittling me. Even if she saw I was right, Maman would never step in during arguments, to avoid offending the older ones—but things were different when I was found to be at fault.

Perhaps the constant oppression I endured at my brother’s and sister’s hands explains my passion for justice and my outrage in the face of humiliation—good things in themselves—but what about my outsized need for attention and my extreme sensitivity, verging on frailty?

My father went further in his diagnosis: watching that cruel and hurtful game play out one day with bewilderment, he intervened in my favor, and addressing Thibaut and Caroline, concluded: “You’ll end up turning her into an idiot.”

And if a father was good for anything, it was that: to administer justice…

*

I saw my father one-on-one when we had dinner together. He would take me to fancy restaurants where I had the chance to taste expensive dishes: oysters, lobster, sumptuous desserts—the height of indulgence, in my eyes, was meringue glacée. But most importantly, I was with my father and I felt good. He was attentive, loving, “respectful.” At last, I was a person in my own right. Our conversation was interspersed with peaceful silences, and sometimes I would reach across the table and take his hand. He never talked to me about his private life, and I never questioned him on the subject, nor did it even cross my mind. He would show up out of nowhere and it never surprised me in the least. The essential thing: he was there, and I was “flushed, enraptured,” as the poet said.

–Translated from the French by Adrian Nathan West

__________________________________

Excerpted from A Father: Puzzle by the late Sibylle Lacan. Translated by Adrian Nathan West. Copyright, The MIT Press, 2019.

Sibylle Lacan

Sibylle Lacan (1940–2013) was Jacques Lacan's second daughter from his first marriage. A translator of Spanish, English, and Russian, she followed A Father with a book devoted to her mother (Points de suspension).