Remembering Merce Cunningham and Radical Dance in Postwar Paris

Marianne Preger-Simon on Dancing with an Icon

“Merce would like to speak with you and Carolyn,” said a smiling administrator of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. The company was performing at Jacob’s Pillow, in western Massachusetts, that July weekend in 2009. I was deeply moved that Merce wanted to say “Goodbye” to me, knowing as I did, as he did, that he was “wavering on the perimeter” of his phenomenal life. The administrator led Carolyn Brown and me down the aisle of the main theater to the front of the orchestra pit. A camera had been set up, this July evening, to transmit the company’s performance to its failing choreographer, home in bed in New York City.

“Hi, Merce, I’m delighted to talk with you.” “How good to see you, Marianne,” came his warm reply.

“I hope no one drops a smoking ball into the orchestra pit tonight,” I teased, recalling an incident from an early Jacob’s Pillow performance that Merce loved to remind me of. (I was the horrified miscreant. My task had been to balance on my hand a ball with smoke emerging from it, while moving down to the front of the stage. I dropped it!) He laughed, as I’d hoped he would. We exchanged a few more words and then, “I love you, Merce, enjoy the performance.” Four days later, he died. What a blessing to be able to say “Good-bye” in such a loving exchange and familiar setting.

*

This story starts 60 years earlier, shortly after the cauldron of destruction that was World War II had ended. Peace was followed in the western world by an explosion of artistic creativity, first in Paris, later in New York. All the collective energy and attention that had been directed toward winning the war were now available for personal creativity and individual exploration.

Drawn by the excitement and fervor of Paris, a young generation of students and artists of all persuasions poured into the city’s winding streets and inexpensive hotels and garrets. An exchange rate of three hundred francs to the dollar made a year of life in France cost about the equivalent of one or two months in America. How gracious and inviting was that!

I was twenty years old when I first met Merce in 1949, near the end of my transformative year in Paris, attending Éducation par le Jeu Dramatique (ÉPJD—Education through Dramatic Play), the drama school founded by the radical and influential director/actor Jean-Louis Barrault. I had come to Paris in 1948, after two years at Cornell University, with the intention of taking part in the Junior Year Abroad program at the Sorbonne, sponsored by Sweetbriar College. That intention was radically altered within a month after my arrival.

*

Into this artistic commotion that was freeing invention and challenging convention, came Merce Cunningham and John Cage, adept at both those cultural shifts.

In late spring of 1949, I learned that Merce Cunningham was giving a dance concert in the studio of a leading modernist, later figurative artist, Jean Hélion, in Paris.

He gives the impression of never being static, but of never making an effort—a continuous, completely unified flow, like the song of a bird.

I had seen Merce’s phenomenal aerial performance in Letter to the World, as part of Martha Graham’s company, several years before I left the States, and admired his dancing enormously, so I made a point of being at the studio event. I found this concert very exciting. Merce’s dancing and his choreography were radically different from Graham’s, differences that I would understand more fully as I became his student. I expressed my enthusiasm in a letter to a friend, written July 15, 1949 (I apparently melded together the studio performance and the brief performance a month later, part of a multi-person event at the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier):

Merce danced the other night—my goodness, I have never seen anything like him in my life. He gives the impression of never being static, but of never making an effort—a continuous, completely unified flow, like the song of a bird—he makes all movements—angular, curved, moments of no movement—anything you want—but the unity and lucidity are so complete—and he has such a perfect understanding and use of space, of his body, of time—it’s really terribly exciting and moving—I didn’t breathe all the way through. That was a solo [I believe it was Root of an Unfocus]. Then he did two trios [actually one trio, Effusions Avant l’Heure1 and a duet, Amores, with Le Clercq] with two women—ballet dancers [Tanaquil Le Clercq and Betty Nichols, both members of the New York City Ballet]—that were in between ballet and modern. Those I liked less because of the ballet principle involved—of static “tableaux”—I always feel that those tableaux are so gratuitous—no reason for them or connection with what follows. But there, too, the movement patterns were exquisite. He really conquers the dimensions in his choreography. And such a fluid body;—a formidable technique, that is so good it becomes secondary in the dance, and the whole thing enters through the observer’s stomach without need of an intellectual interpretation or assimilation.

I suspect that my discomfort with the “static ‘tableaux’” was less about “ballet principles” than about early indications of Merce’s interest in stillness as part of movement, which remarkably distinguished him from so many other contemporary choreographers. I later came to value and appreciate the stillness in such dances as Septet and Springweather and People.

What is interesting to me is that what I was perceiving with so much delighted excitement as a member of the audience, was being experienced as rather chaotic from the point of view of one of the dancers, Betty Nichols.

Here is her description of the making and performance of Merce’s dance concert, excerpted from an interview with Ballet Review:

Nichols: 1949 was a fantastic year in Paris. Everything was happening. Everybody was there. It was recovering from the war fast.

Tanny [Tanaquil Le Clercq] and I had been in Paris a week. We were walking on the pavé of St. Chapelle and heard “Betty! Tanny!” We turned; it was Merce Cunningham and John Cage. “We’re going to have a recital. You’ve got to do it with us.” I knew Merce because he was at SAB [School of American Ballet]. He took class. I didn’t know him personally, but Tanny had danced Merce’s Seasons at Ballet Society.

The Cage music was very difficult. I remember being terrified because he gave us such liberty—already—that I said, “I’m never going to know when to come in.”

“That’s all right, that’s all right,” Merce said. “You’ll find it.” But I was never sure. I don’t think I was doing it the same each time.

BR: He didn’t care.

Nichols: Exactly, it didn’t seem to matter. At that time I didn’t know anything about that. Maybe even Merce didn’t. Maybe that was just beginning. We had ballet shoes and we wore rehearsal clothes. We had tights and a sweater. Pat McBride’s mother used to knit these sweaters for dancers.

It was done in the painter Jean Hélion’s studio. There was tremendous publicity about the program. It was the first time Paris had ever seen anything like that, and it was so astounding that they didn’t know how to criticize it. So what they said was—they always fall back on this when they can’t think of anything else—“It was so beautiful.” Giacometti was there, and Alice B. Toklas. Le tout Paris came [meaning, everybody who was notable].

I was impressed by the elegance of both Nichols and Le Clercq and visually aware of their ballet training from the way they moved. However, as my letter indicates, Merce’s performance overwhelmed every other impression, and became the complete focus of my attention. Furthermore, balletic movement was familiar to me, whereas his personal style was so new and electric.

At last, after eight months I can really dance—and with him! Imagine. I’m exploding with joy—how I’ve missed dancing.

Ralph Coburn, who was also at the concert, told me that he and his friend Ellsworth Kelly, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage, the composer, were staying in the same hotel, the Hotel de Bourgogne on the Ile St. Louis. He informed me that Merce was looking for a studio to work in.

That was all the encouragement I needed. Several days later I sat outside the hotel until Merce came out, then accosted him and informed him that I knew of a studio where he could work and also teach a class.

Part of the curriculum of ÉPJD had been a dance class held in studio 121 at the Salle Pleyel, originally taught by the gifted German modern dancer, Ludolf Schild, student of Mary Wigman and familiar with Martha Graham’s work. I described my first sight of Schild in a letter from October 1948:

My goodness was I shocked. I’d expected, for some reason, an older man. Instead appeared this magnificent looking young man. He has great troughs in his cheeks, and deep-set burning eyes, and he’s long and thin. He has a small beard all around the edge of his jaw—just beautiful. He walks with a cane because of an operation he had last year . . . Everyone hopes he will be able to dance again. At one point after class, he stood in front of a mirror with his cane and, with an ironic smile, said, “Voilà, le danseur Schild” [There is the dancer, Schild]. Then he turned and saw my long face and said, “C’est triste, eh?” [It’s sad, eh?]. And it was—not only because it would be horrible not to be able to dance again, but also because he would die in his soul if he were to become bitter as a result.

Schild died of cancer in early June 1949. His classes had been taken over by his protégée, Jacqueline Levant, when he became too sick to teach. Jacqueline had been his devoted dance partner, collaborator, and lover. She was interested in having important guests teaching in studio 121. She assured me she’d be happy to have Merce teach there, so she could learn from another master. (She went on to teach at ÉPJD for three more years, and to perform in the Ballets Modernes de Paris from 1953 to 1955.) This was all amicably arranged, and so began my life in the orbit of Merce Cunningham.

Here is an account of my meeting with Merce, from a letter I wrote to a friend on June 19, 1949:

Merce Cunningham is here and I met him last week—spent an hour talking to him, discussing dance, theatre, etc. I was able to give various information he’s been searching for since arriving. Yesterday, he came to my school to see our mime course, and was very enthusiastic and interested, and kept whispering observations and comments to me throughout. He is an angel—charming and so interested/interesting. And he is teaching all summer here beginning Tuesday!! At last, after eight months I can really dance—and with him! Imagine. I’m exploding with joy—how I’ve missed dancing—it’s surprising, considering what a new acquaintance it is.

Dancing was indeed a new acquaintance of mine. When I first arrived at Cornell in 1946, I developed a strained achilles tendon in one leg from walking up and down the hilly streets of Ithaca. When the college doctor helped me into a small whirlpool foot bath, he said, “You should dance. You have such flexible feet.” So I thought, “Yes, what a nice idea!” and joined the Dance Club, led by a Graham-trained dancer, May Atherton. As I later discovered, flexible feet were definitely not one of my major assets—but I’m eternally grateful for his incorrect analysis. It pushed me into a splendid world.

*

Merce upset many applecarts in the dance canon, as his choreography developed over 60 years. In the first decade of that development he received largely puzzled looks from whatever public attended performances, and mostly derogatory reviews on those few occasions when a critic deigned to review his performance. The exception to this lack of acceptance occurred during our West Coast tour in 1955, a rare month of enthusiasm from a totally new audience. But it took a good ten years for the dance public to relinquish its expectations of the familiar and develop an appetite for the dances produced by a remarkable and completely novel choreographer. Fortunately, the transition happened.

One applecart Merce did not seek to overturn was the convention of male-female duets, in which the man was the tender and devoted supporter of the woman. There were certainly duets between men or between women, but these never matched in intensity his exquisite male-female duets. Certainly the most obvious difference between mixed-gender duets and same-gender duets is the difference between the male body and the female body, both physically and qualitatively. Since Merce was very tuned in to the way his dancers moved, and choreographed accordingly, this sensitivity of his would be a primary motivating force in the kind of movements he would choose for mixed-gender duets, compared to same-gender duets. It is my belief that this was a prime reason for his choice in partnering.

But perhaps not the only one.

It is hard for me to imagine that Merce would allow himself to be pressured by custom into creating male-female duets. He gave no indication that convention ever occupied space in his imagination; on the contrary, it seemed to provide a stimulus for invention. So there must be an additional motivation that impelled him to carry on what we think of as a tradition.

The fact that Merce was gay in no way prevented him from feeling warm and affectionate toward women, making strong connections with us, and often loving us in his own particular fashion. It would not require a stretch of the imagination to assume that he could enjoy creating such brilliantly intimate and tender duets between a man and a woman. Perhaps this was a means of bringing a part of his fantasy life into being; who can ever know? He was a complex and mysterious human being who expressed everything in his choreography, maybe even parts of himself that never appeared anywhere else.

_________________________________________

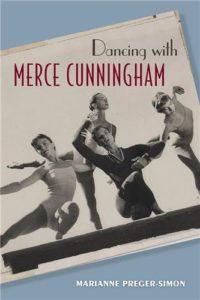

Adapted from Dancing with Merce Cunningham by Marianne Preger-Simon. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019. Reprinted with permission.

Marianne Preger-Simon

Marianne Preger-Simon, born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1929, was a founding member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, with which she danced between 1950 and 1958. During those years, she taught dance, drama, and world literature at the New Lincoln School in Manhattan. After leaving the stage to start a family, she received her Ed.D. from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, led workshops in the United States and Canada in Values Clarification and Mother/ Daughter Relationships, and has practiced psychotherapy for forty years. Married twice, she has birthed two children and was blessed with four more through marriage. Her life is now replete with grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and a large, lively, loving family.