Remembering David Ruggles, the radical abolitionist who opened the first Black-owned bookstore.

A Black History month reflection.

This Black History Month is the fraughtest. Maybe even apex fraught.

As many hard-won minority group commemorations are being actively scrubbed from government websites, we the recognized are asked to consider what those commemorations have come to mean under elite capture. When your very existence is contested, what are the limits of federal recognition?

As Frederick Douglass once put it, “What to the slave is the fourth of July?”

In a wonderful Substack reflection (“A Black History Month Love Note“), author Kaitlyn Greenidge reminds us:

Black History Month began not as a business move or a way to build monetary wealth or a desire for white American understanding or a marketing push. It was an effort of Black librarians and researchers to preserve memory and build self. It was started not by CEOs or ‘disrupters’ but by the people who keep and safeguard our archives.

One archivist well worth remembering is the abolitionist David Ruggles.

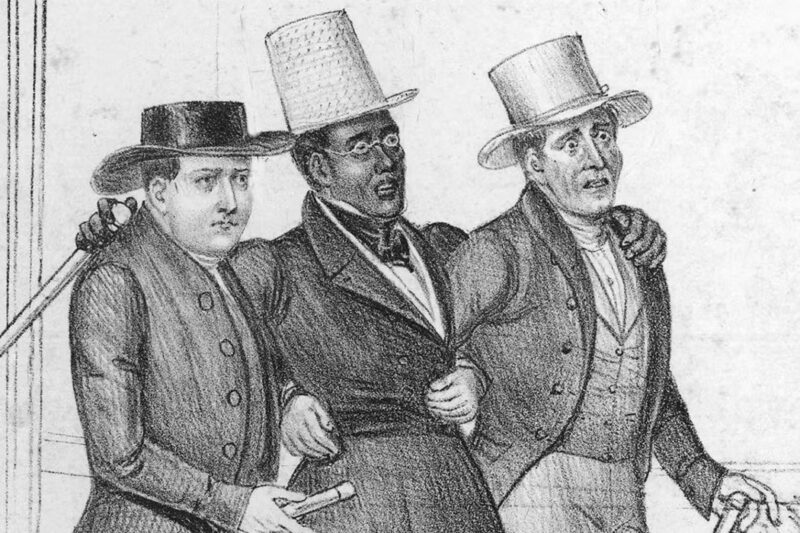

As Ashawnta Jackson reports in JSTOR, David Ruggles was born into freedom in 1810. A journalist who worked for The Emancipator and The Liberator, Ruggles spent his life committed to abolition. He eventually went on to found his own newspaper, Mirror of Liberty, and was an early conductor of the Underground Railroad. He personally sheltered hundreds of escaped enslaved people at the height of the Fugitive Slave Act—Frederick Douglass himself being one.

His first public endeavor was a grocery store, located at One Cortlandt Street in New York. This store, which subscribed to the Quaker-supported Free Produce movement and sold only produce made without slave labor, also served as a reading room for Black New Yorkers who were then denied access to the state’s public libraries.

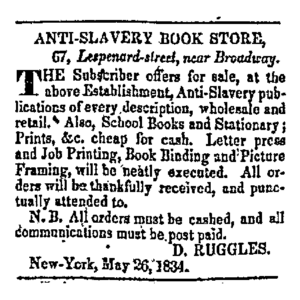

At 24, Ruggles opened the first (known) Black-owned bookstore, on Lipsenard Street. He stocked his stacks “with abolitionist and feminist publications.”

This space also served as a meeting place for groups like the New York Manumission Society, or the New York Committee of Vigilance—an abolitionist working group that Ruggles co-founded. Haters in the press referred to the joint as an “incendiary depot.”

The depot was often caught in enemy crosshairs. A mob once set fire to his collection. And Ruggles himself was often tormented (and once, arrested) for his activism.

All that good work took its toll. Ruggles spent his late thirties seeking and then extolling the water cure at a minor magic mountain in Northampton, Massachusetts. He died at 39, enjoying the reputation of a super radical, too extra for even some of his abolitionist peers.

Ruggles’ name isn’t usually uttered in the same breath as those major Black history icons (see: Douglass) but I can only explain that by erasure. Which of course we’re likely to get more of, institutionally. The way things are going.

But here’s Greenidge again.

The intentions of Black History month have nothing to do with a multinational corporation’s shareholders or a tech CEO who has never been more curious about anything other than himself. It’s reminding us that even when the dominant narrative insists that Blackness is on the outs (an absurd belief) that ‘DEI’ has been eliminated, we keep creating and building and planning and making.”

It’s a useful time to remember our radical literary histories. The movers and shakers who made havens against prevailing winds. So this Tuesday, I’m pouring one out for David Ruggles.

May we all make or find refuge in incendiary, communal space.

Brittany Allen

Brittany K. Allen is a writer and actor living in Brooklyn.