Remembering Christa McAuliffe and the Challenger Disaster

Joyce Maynard on the Day She Spent with the Teacher-Turned-Astronaut

I was a seven-year-old second grader when NASA sent the first American astronaut into space.

The entire student body of Oyster River Elementary School gathered in the cafeteria to watch the launch on the screen of a single black-and-white television set, wheeled in on a cart for the occasion. That day, 200 children counted down in unison. When the space capsule broke away from the launch pad, we cheered and threw erasers into the air.

For us, this was more than the first manned space launch. Where I came from—New Hampshire—a place where (it often seemed to me) a back-to-school shopping trip to the city was a major adventure, never mind leaving the planet. The idea that a person from my world could blast into space—if only for a matter of minutes—signaled all kinds of possibilities about my own future.

Of course, that person was a man. I was a girl. In the year 1961, that made all the difference.

For a while there, over the years that followed, the space program occupied considerable attention. I read about the astronauts and their families in the pages of Life Magazine. Here were normal, ordinary people, embarking on extraordinary adventures. The fact that this was so allowed me to imagine other forms of flight for me, too. Then came the summer of 1969. Neil Armstrong. The moon. One small step for Man…

Today, I’d ask the question—why only “for Man”? Where were the women in this story? But the girl I was then—at age 15—had been, all her life, so accustomed to the exclusion of my gender in the language I heard from male writers, politicians, newscasters and teachers, that I have no memory of registering offense at the line.

Eventually, NASA named a woman astronaut, Sally Ride. But by this time, the glamor of the space program was fading. By the mid 80s—married now, working as a writer and raising three young children in my home state of New Hampshire—I doubt I could have named a single astronaut, or identified the name of NASA’s most recent mission.

What kind of marriage would it be if he kept the person he loved from pursuing her dreams? I thought about my own marriage then. What my husband might have said if I’d suggested that I might want to explore space.

Then—in an effort to recapture the imagination and enthusiasm of the American public—Ronald Reagan announced the creation of a new initiative in which a civilian, chosen from among public school teachers around the country, would join the current roster of astronauts on a mission. Thousands applied. Finalists were named. When the day came to announce the first-ever Teacher in Space, the one selected was Christa McAuliffe, a New Hampshire high school teacher, wife and mother of two young children—in her thirties, like me—who lived just a half-hour’s drive from where my husband and I were raising our family.

Back in those days, I aspired to write novels, but to pay the bills, I wrote a lot of articles for women’s magazines. I pitched a profile of Christa, and Family Circle hired me to write it, a date for our meeting set. After negotiating with my husband to watch our children for a few hours (these were still days when even good men spoke of “babysitting” their children), I drove off to Concord to meet Christa McAuliffe.

She was a spectacularly well-organized women. This was long before any of us carried cell phones attached to the dashboards of our vehicles, but she had a row of Post-It notes laid out—next to the chicken defrosting for that night’s dinner with To Do lists for every day of the week written down on them, and the phone number for NASA on her refrigerator door, attached with alphabet magnets. In the middle of a sentence she’d suddenly reach for her pencil and jot down something. “Black high-top sneakers for Scott.” “Get more checks.” If the phone rang when she was in the middle of a sentence, she’d come back five minutes later and finish it—picking up at the exact place in the discussion where we’d left off, without missing a beat.

We spoke about her excitement over being chosen to go into space, and her hope that her presence on the mission, and the science lessons she would teach from inside the Challenger, might inspire a new generation. In the years when Christa and I grew up, women didn’t get to be astronauts. They married or gave birth to them.

A phrase had been coined—maybe by Christa herself, more likely NASA: Reach for the stars. What lesson could a parent impart to our children, more hopeful and ambitious than that one?

I liked her. She was brisk, confident; she paid attention to things. (Asked about the ages of my children, inquired about my work. Knew the names of students she’d taught ten years ago.) She had met her husband Steve—same name as my husband—when they were both 15; they had been together more than 20 years, and though he had been, for most of that time, the kind of husband who doesn’t know where the cleanser is kept, he was totally behind her when she said she wanted to go up in space. They both seemed clear on that—surprised that there would be any question. What kind of marriage would it be if he kept the person he loved from pursuing her dreams?

I thought about my own marriage then. What my husband might have said if I’d suggested that I might want to explore space.

Because time was so short, I rode along with her while she ran errands. We drove in her minivan to the local TV station where Christa taped a show with a minister and a priest about the religious implications of space travel; stopped by the bank, the post office and then the supermarket to pick up peanut butter. She gave another television interview and posed for pictures for a couple of magazines. She returned someone’s library book. She picked up her son at school and listened to him talk about his first day.

On the ground, people were still cheering—briefly anyway. It took a number of seconds before those in the crowd began to grasp that this wasn’t supposed to be happening.

After that, she was supposed to pick up Caroline at the babysitter’s and take both her children to a friend’s house for the rest of the afternoon. Scott wanted to be with his mother, so he came along with us to the doctor’s office (to pick up Caroline’s immunization records for kindergarten) and to the grocery store, again, to order meat for 50 people for a family party she was giving that weekend. Then we stopped for an ice cream cone. Christa had peppermint. Scott said in a small, proud voice that maybe they’d name the flavor after her now.

Everywhere Christa and I stopped that day, people recognized her, of course. “Reach for the stars!” they called out.

After that I went home to my own family, to my own collection of lists and phone numbers and refrigerator magnets and errands, vaccination forms. It had been my daughter’s first day of school, too, and of course I wanted to hear all about that.

Christa called me once from Houston to fill me in on how things were going. She loved it there. I called her husband, Steve, to hear how he and their children were doing, and he told me that when he got the children home every evening, they’d say, “Let’s see what Mr. Microwave has for us tonight.” Christa had left him with lists of neighbors to call on, phone numbers of babysitters and doctors and take-out-food places. Already, he said, he had a whole new understanding of what it was she’d been doing all these years. “Wait till she gets home, though,” he told me. “I plan to slip back to my old habits just as far as she’ll let me.”

We all know the next chapter in the story.

The space shuttle Challenger, with its seven crew members (one of them, Christa McAuliffe) blasted off the launch pad on January 28, 1986. I remember seeing my daughter off to school that morning. She was in second grade, the age I’d been when my own second grade class had gathered to watch the launch of Friendship 7. All week the news had reported the weather at Cape Canaveral as unseasonably cold. But now NASA was saying the Challenger was good to go.

At home with my youngest son, not yet two years old, I turned on the television. There were bleachers set up for a group of VIP spectators, including some of Christa’s students from Concord High, and her family, and the child star of the movie, A Christmas Story, bundled up in winter jackets. Then came images of the astronauts making their way to the space capsule—Christa smiling and waving and looking no different than she had when she’d caught sight of me in that parking lot a few months earlier and invited me to hop into her minivan.

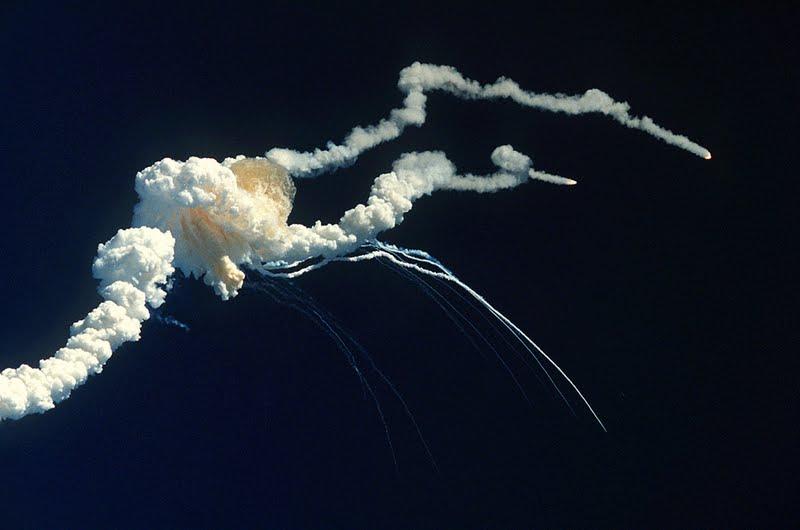

The countdown began. All eyes on the launch pad. Ten nine eight seven… lift off. A perfectly blue sky. Glorious billows of smoke, as the shuttle left the ground. Cheers from the crowd. The face of Christa’s parents on the television screen, smiling and cheering.

Less than a minute later, we saw a second billow of smoke, only this time there seemed to be two separate plumes going in opposite directions. On the ground, people were still cheering—briefly anyway. It took a number of seconds before those in the crowd began to grasp that this wasn’t supposed to be happening.

The generations of young people who came out of those times, and those who followed them, are undeniably less likely to trust in the institutions of government.

Then came the looks of horror on those same previously exultant faces. Someone—Christa’s sister, I thought—was leading her stunned parents away. The announcer stepped in, his face so grim we knew, even before he spoke, what he would say.

By nightfall, when the president addressed the nation, we already knew what had happened, though it would take longer to learn why. As they had done when Lee Harvey Oswald fired on the convertible carrying JFK and Jackie, and when Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald—live, on national television—and as they would do again, some years later, when the planes crashed into the Twin Towers, the networks endlessly played and replayed the footage of those terrible seconds. Few Americans who were alive and conscious in the year 1986 will forget them.

NASA had created this event—and promoted it with dazzling success—for the purpose of re-igniting enthusiasm for the space program. In Christa McAuliffe they found the perfect player in the drama: an ordinary (but extraordinary) woman we could all identify with, who made us care, again, about the idea of spending billions of dollars, sending Americans into space. Because the woman they’d chosen was also a teacher, and a mother, even young children had learned about the Challenger, and followed the story of Christa McAuliffe. When she stepped out on the tarmac that morning, and climbed into the space capsule, all of America seemed to be going up with her. And of course, the fact that we felt that way made her fall feel like ours, as well.That night, after putting my children to bed, I stepped out into the snowy darkness behind our house and wept for a woman I barely knew, and for her children, and her husband. I knew I would one day be happy and hopeful again, but that night it was hard to imagine when that day might come.

In the years that followed that one terrible morning of her childhood, my daughter would know many deaths—the cancer that took her grandmother, and then her uncle, the suicide of a high school classmate. But January 28, 1986, the month before Audrey’s eighth birthday, marked the first, and I believe it was a turning point.

Later, the story got darker, as we learned about the faulty O-ring, and the increasingly desperate messages sent by the most knowledgeable engineers overseeing the Challenger’s design and safety, imploring NASA to hold off on the launch. At temperatures like those at Cape Canaveral the morning they’d given the go-ahead, those O-rings were known to be inadequate.

There is personal grief—the kind each of us suffers, alone, when someone we love dies—and then there is this other kind of sorrow, that you share with the world—when the particular details unique to each of our lives are lived against the backdrop of another brand of grief, shared by us all. We experienced such a time as a nation in the last week of November, 1963, and on September 11, 2001. We’ve been going through one of those times over the course of the past ten months since the start of the pandemic.

The Challenger explosion, that took place 35 years ago this week, when a generation of school children stared numbly at a billowing cloud of smoke the television screen, was another such time—a defining moment of their growing up years. I might hypothesize that this was the moment—one of them, anyway—that led to a new brand of national cynicism taking hold. The generations of young people who came out of those times, and those who followed them, are undeniably less likely to trust in the institutions of government, the infallibility of our so-called experts, the invulnerability of our heroes.

I still believe in science. But the last 35 years have also revealed the stunning hubris of those in possession of scientific knowledge—whether about O-rings, or climate change—who fail to heed it in ways that lead to disaster.

The 35 years that have passed since January 28, 1986 contain too much history—national as well as persona —to summarize in a single broad sweep. My marriage to my children’s father ended long ago. The children all grew up, and survived—some to raise children of their own. I did finally get to write a novel, and then many more. A school in Concord New Hampshire now bears Christa McAuliffe’s name, as does a planetarium there. It may be worth noting that school children who once gathered for the countdown of a space shuttle now receive instruction, in their classrooms, on what to do if a school shooter starts firing. They are probably more likely to aspire to being DJs and Tik Tok stars than astronauts.

But there’s still this. A week short of the 35-year anniversary of the Challenger explosion, and the death of Christa McAuliffe and her fellow crewmembers, a new generation of children watched the inauguration of the first woman to serve as vice president. Call it what it is: one very large step for humankind.

Joyce Maynard

Joyce Maynard is the author of nine previous novels and five books of nonfiction, as well as the syndicated column, “Domestic Affairs.” Her bestselling memoir, At Home in the World, has been translated into sixteen languages. Her novels To Die For and Labor Day were both adapted for film. Her new novel Count the Ways will be published by William Morrow in May, 2021.