Remember when Toni Morrison smacked down a racist biography of Angela Davis?

It happened in the fall of 1972. The Watergate scandal was in its infancy, Bobby Fischer had just defeated Boris Spassky in a Cold War chess match, and the inspirational political activist, philosopher, academic, and author Angela Davis had recently been released from prison.

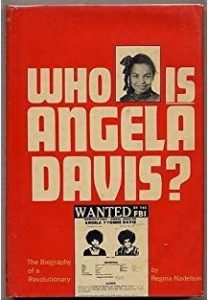

Toni Morrison—arguably the greatest fiction writer this country has ever produced who passed away one year ago today at the age of 86—was, in 1972, working as an editor at Random House, having published her debut novel, The Bluest Eye, just two years previous. Around that time, some fool (or perhaps diabolical genius?) of an assigning editor at the New York Times asked her to review Who is Angela Davis?, an offensive quasi-biography that eschewed real research in favor of condescending to its subject and trading in lazy, racist stereotypes.

Morrison duly obliged.

Here is the marvelous evisceration in full:

“On the other hand, who is Regina Nadelson and why is she behaving like Harriet Beecher Stowe, another simpatico white girl who felt she was privy to the secret of how black revolutionaries got that way? How Liza could get to the point of actually crossing the ice or how Angela Davis got to the point of actually joining the Communist party was quite naturally that white intelligence informed them both; and since Harriet was prey to the scientific racism of her day she attributed Liza’s feistiness to the genetic transference of information via white blood; but Regina lives in the 20th century and is an enlightened racist who knows about cultural determinism, which is to say Angela got her courage not from white blood but white culture and that her sublime militancy was spawned by white teachers, white boyfriends, white psychoanalysts, and a special brand of white terror perpetrated on some respectable colored folks for how else could she dally with Black Panthers and fight Ronald Reagan and carry the Card, for surely no black folks influenced her (except abstract victims and her middle class—read white-oriented—family) which is why Miss Regina who knew Angela at Elisabeth Irwin High School didn’t take the trouble to interview any blacks as she went about collecting her data and rejecting all eyeball to eyeball or flesh to flesh contact with any of the ‘other blacks’ with whom Angela tried to form a Black Student Union or the ‘adherents’ that were drawn into it or the ‘other black groups’ she worked with before joining the party or those other irrelevant black souls Angela knew all her life, for, as Miss Regina’s labels show, Angela’s ‘people’ were not worth talking to anyway for whenever she needed a black view all she had to do was quote Frazier, DuBois, Baldwin or some other black with a real name, and not even Angela herself was a reliable source, for in the chapter ‘Conversations in Jail’ Miss Regina quotes exactly 23 words Angela actually spoke and they were directed to Margaret Burnham, the rest of them being culled from writings and speeches, so the consequence of this singularly parochial research is that Angela Davis is revealed to be pretty much like Regina Nadelson, an American. ‘People see her as a black leader and as a liberated woman. There is something else that matters to me: she is an American.’ And as for her personal regard for her subject, Miss Regina likes her; ‘She is kind and funny.’ Yessum, Miss Regina. We all are.

She folded her legs again, letting her hands fly from her lap like wings: ‘I knew there would be a lot of things written about me and this one, at least, would be accurate; I thought I would have some control over it. But look what she’s done. She’s distorted everything.’

I suck my teeth. Her lawyers shakes his head.

Who Is Angela Davis? is a Cyclopean view of Angela Davis that leaves the reader with a wholly useless biography, somehow offensive in its one-eyed stare. Maybe because the other thing about Cyclops was that he too had a taste for human flesh.”

Dan Sheehan

Dan Sheehan is the author of the novel Restless Souls (Ig Publishing) and Editor-in-Chief of Book Marks.