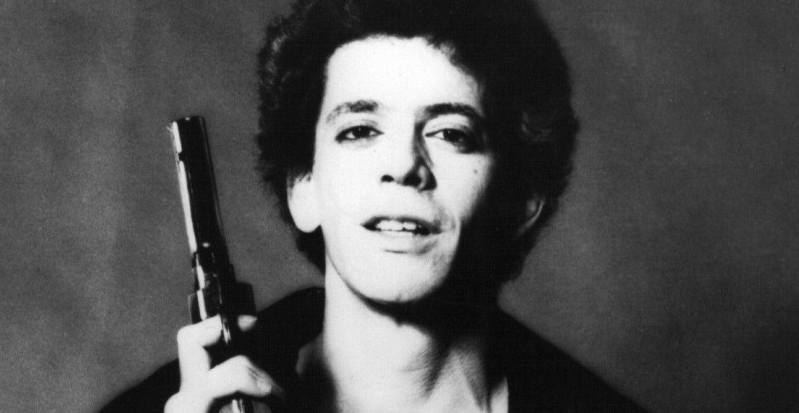

“Relentless F*cking Noise”: Lou Reed on Making an Unlistenable Album

Allan Jones Chats with the Former Velvet Underground Frontman About Metal Machine Music

London, April 1977

When I turn up at the offices of Arista Records to interview Lou Reed for the first time, I’m taken aside and told quite firmly that certain questions I may have for Lou are off-limits. I’m particularly discouraged from asking, for instance, anything about The Velvet Underground, David Bowie, Andy Warhol, the much-lambasted Berlin album and just about anything else of conspicuous interest. I’m not quite sure what this will leave us to talk about, unless Lou’s developed a recent passion for needlepoint embroidery or cattle farming about which he might care to wax lyrical for however long I get with him.

It turns out that by some remarkable chance, I hit it off with Lou. There’s an obligatory barrage of colorful abuse, a well-practiced nastiness that makes me laugh rather than terrorize me, which seems to be his intention. It makes for a bumpy first 20 minutes. Then, he suddenly softens, offers me a drink, pouring startlingly large measures of Johnnie Walker Red into a couple of glasses and handing one to me, leaving the top off for immediate refills and sending out for another. He seems to be settling in for the long haul.

You can’t control that record. You have to go wherever it goes.I decide to ignore the instructions I’ve been given and ask him whatever the fuck I want. Which I do, Lou quickly getting into it. Any excuse to talk about himself, it seems, and he’s off at a gallop. We talk about The Velvet Underground, Andy, Bowie, Berlin—”The way that album was overlooked was probably the biggest disappointment I ever faced.” Eventually, we get around to the notorious Metal Machine Music, a double album of relentless feedback, by general agreement unlistenable. I review it for Melody Maker when it comes out in August 1975 and can’t decide whether it’s a Warholian prank, a conceptual joke or the brutal fulfillment of Andy Warhol’s advice to The Velvet Underground to always leave their audience wanting less.

Lou laughs when I mention the album and the reaction to its release.

“RCA didn’t want to release it,” he says, opening the second bottle of Johnnie Walker Red, filling our glasses. “They thought it would be detrimental to my career, which was a notion that made me laugh. When have I ever done anything that someone didn’t think was detrimental to my fucking career? They took it off the market after three weeks. You couldn’t get it anywhere. It was so fucking fabulous. It was so exciting. No one else was doing anything that could have got that kind of reaction.

“Everything had become so fucking boring and predictable. Then along came Metal Machine Music. It was like a fucking bomb going off. It was like Andy’s Soup Cans. I mean, the idea in and of itself was good. Brilliant, even. But for the full impact, you had to go through all the motions of execution.

“Everyone thought I was mad. They thought it would really finish me. Kill me, you know. Initially, the reaction was, ‘We don’t want any more Lou Reed records.’ I said, ‘Fine. I won’t make any more.’ Then, of course, they turn around and say, ‘Aw, c’mon, Lou. You don’t mean it. You can’t do that.’ I said, ‘What do you mean? You said you didn’t want any more Lou Reed records.’ And they said, ‘Please.’ And I said, ‘Maybe.’ Then I put out Coney Island Baby and they hit that on the head as well. I love it. We were right back where we started.

“These people are too fucking much. They want me to make record and when I do, they tell me I’m a fucking parody of myself. But who better to parody? If I’m going to mimic anyone, it might as well be Lou Reed. I mean, I can do Lou Reed better than anyone, and a lot of people try to sound like me. Some of them have even made a lot more money than me by sounding like Lou Reed.

Anyway, RCA had their guys taking the album out to the Top 40 radio stations. Can you imagine the look on some guy’s face when he brings it to some program controller and says, ‘Hey gang, anyone wanna listen to Lou Reed’s new album?’ And they’re expecting, you know, fucking ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ or something. And they put it on and it’s just this fucking noise. They go, ‘Get that the fuck off. Get it the fuck out of here.’ It’s the worst thing they’ve ever fucking heard. It’s like a contagion. It’s poisoning them. It was fucking hysterical. Excruciatingly funny.

“They take it to CHUM radio in Canada. Like the fucking Canadians are going get it. It’s not a moose or an elk or ice hockey, so the fucking Canadians aren’t going to get it. The fucking Canadians don’t get anything. But they take it to CHUM radio, anyway. The guys at CHUM are like, ‘Is there something wrong with the record? It doesn’t sound right. Should we try another side?’ And they turn it over, and it’s the same fucking thing. The same relentless fucking noise.

“That record is the closest thing I’ve ever come to perfection. It’s also the only record I know that attacks the listener. Even when it gets to the end of the last side, it still won’t fucking stop. You have to get up and remove it from the fucking turntable yourself. It’s impossible to even think when the thing’s on.

“It destroys you. You can’t complete a fucking thought. You can’t even comprehend what it’s doing to you. You’re literally driven to taking the miserable fucking thing off. You can’t control that record. You have to go wherever it goes, which is basically—well, who the fuck knows? It depends on the weather.

It’s like someone hitting you on the side of the head. It’s marvelous.“It’s total gibberish, from start to finish. Half of it’s backwards. What we did when we recorded it in Quad was to flip over the tape of the first side and just play it backwards to get the second side. We cut it to exactly the same length. It had to be the same length by definition. If it’s that long forward, it’s that length backwards.

“It didn’t sound appreciably different, so we stuck with it. When I went to the RCA studios to cut the thing in Quad, I said to the guy who was in charge of the technicians, ‘Whatever you do, don’t tell them that all we’re doing is playing the tape backwards. That won’t be technical enough for them. Make up some kind of complicated technical reason and then get them to do it.’ And that’s what he did.

“I was really excited, you know, about recording it in Quad. There were only two Quad systems in New York at the time, so I was delighted. I ran over to a friend of mine and I told him I’d jived RCA into letting me have a crack at their Quad system and we listened to the tape, and he said, ‘Quad? It’s barely in fucking stereo.’

“It’s not even balanced properly, that record. You can’t even balance the fucking thing. If you wear headphones, sometimes the sound will dip over and take you with it. It’s like someone hitting you on the side of the head. It’s marvelous. Complete fucking gibberish. But I can invent such wonderful technical reasons for everything about it.

“Like those symbols on the back cover. Those DB symbols and kilohertz signs? I showed them to another friend of mine and asked him what I’d written. He told me that one quarter of side one, from what I’d written, could only be heard by dogs and after that nothing living or breathing that he could think of would be able to hear anything.

“He said, ‘Is that what you meant to say?’

“I didn’t know. I’d just picked up a copy of a stereo magazine and copied out some symbols. I didn’t have a fucking clue what they meant. My friend was astonished. ‘It’s total gibberish,’ he said. ‘This sign means animals with high sensitivity can hear it. But the rest means that nothing human or otherwise can hear it. Is that really what you meant to say?’

“I said, ‘Yes. That’s exactly what I meant to say.’

“And he just said, ‘Congratulations.'”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Too Late to Stop Now: More Rock’n’roll War Stories by Allan Jones. Copyright © 2023. Run with permission of the author. Courtesy of Bloomsbury Caravel, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.