Rebecca Solnit on Meghann Riepenhoff’s Cyanotype Prints Made in Freezing Landscapes

“The processes of photography were liquid for most of the medium’s history...”

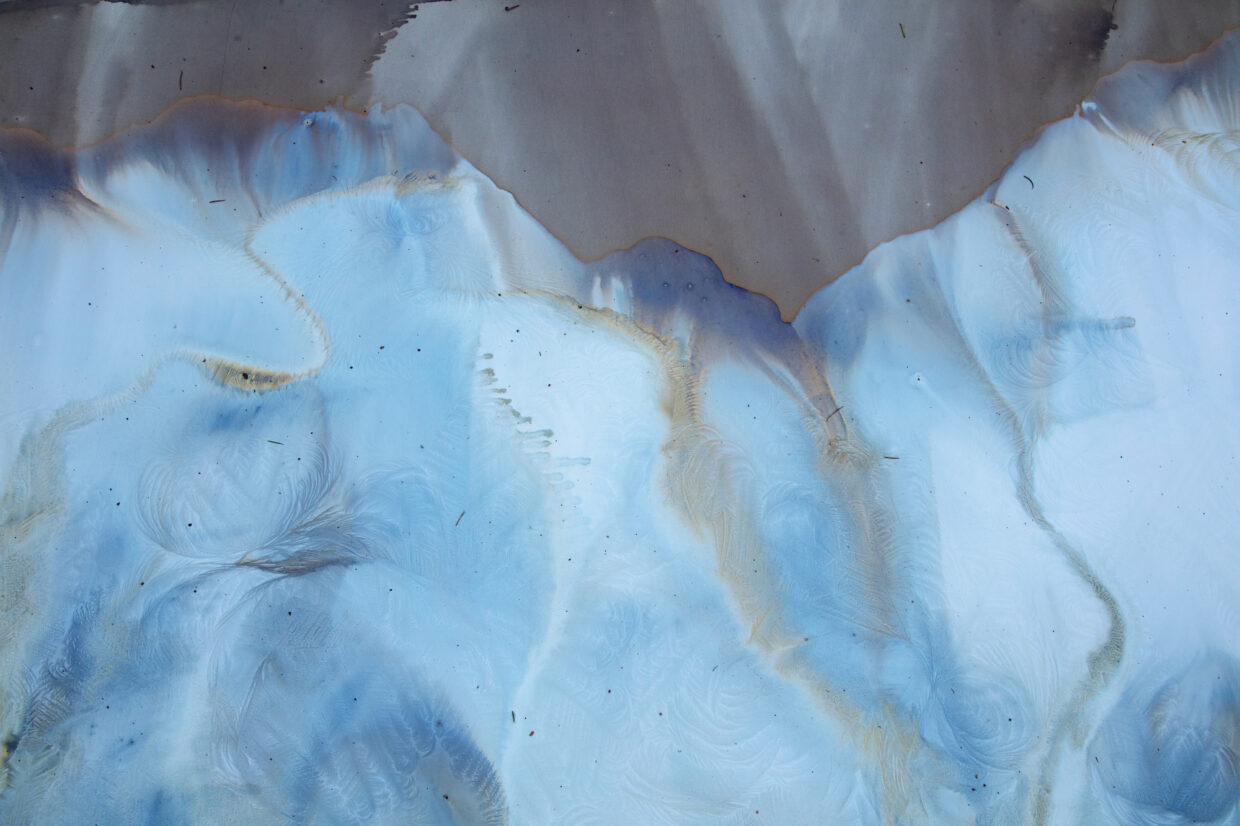

Ice, #9316 © Meghann Riepenhoff, from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice © Radius Books.

Ice, #9316 © Meghann Riepenhoff, from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice © Radius Books.

Often described as though it was accident rather than alignment, coincidence means the coming together of two things in a more or less harmonious version of a collision, and it is in that spirit a coincidence that at a certain point in the European middle ages the mother of God became an important figure of mercy and intercession and femininity in Christian life as a new source of blue pigment arrived—pulverized lapis lazuli from far-off Afghanistan—that allowed painters to depict intense and vivid shades of blue as never before, and this blue known as ultramarine was most particularly dedicated to depicting her robes, and blue became her color, all of which I delved into after returning to view some of these paintings in which the robes pour off her like water and ripple around her feet as if in inlets and bays, paintings that make me wonder if rather than thinking of all that blue as celestial, the garb of the queen of heaven, as she was also known, it makes her aquatic, oceanic, marine, ultramarine, a living and lifegiving spring or lake, an ocean giving rise to new conditions for life as the cyanobacteria did, an entity whose liquidity is also the female condition in ways that have sometimes worried men, the porousness of those bodies that men sometimes enter and babies sometimes exit, of the flow of blood and amniotic fluid and words, of the undermining of the fantasy of solidity that is the homophobic ideal of impenetrable and autonomous manhood, when in actuality everyone and each of us is a container punctuated by openings with which to smell, to hear, to breathe, to be penetrated as a camera’s aperture is by light itself and relies constantly on inhaling and exhaling, a sort of drinking of the sky and its oxygen, on eating and excreting, the body that is also an erratic fountain of tears, urine, spit, sweat, ejaculate, the menses of fertility and the blood of injury, to say nothing of all the internal secretions of the glands, and is itself two thirds or more water, the blood an interior ocean with the salinity of an ocean moving in waves pumped along by the heart, the water of the body finding an echo in what we call a body of water, and bodies of water are themselves also not discrete, as in self-contained, but forever being added to by tributary streams and rivers and springs or being drained by distributary channels or evaporating into humidity and clouds that become storms, rain, hail, snow, sleet, returning to the solid and liquid surface of the earth: all of this to say that in one such medieval Nativity, the robe flows like water, the child who is also a god lies on a scallop of deep blue on the ground as if afloat, the god whose blood will become a symbol in a church whose rites are full of liquidities, including transubstantiation, anointment, and baptism by immersion or sprinkling with water that has been blessed, and implicit in all this is the possibility that the divine mother so often called a vessel is herself a body of water, which is a reminder of that inward sea of darkness in which each of us swam during the months before birth, and that a camera—a word that means chamber or room—is or was also a vessel of darkness into which light penetrates to impregnate the film with its image, and that the Bible is a book written by desert-dwellers in which the finding of water is often a miracle and a gift.

Ice, #6039 © Meghann Riepenhoff, from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice © Radius Books.

Ice, #6039 © Meghann Riepenhoff, from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice © Radius Books.

*

The processes of photography were liquid for most of the medium’s history, more so and less so in various media, utterly so in Muybridge’s wet-plate era when the glass negative had to be coated with emulsion in a dark-tent on site, less so when wet plates were replaced by dry-plate film and then celluloid strip and sheet film late in the nineteenth century, but even when I learned darkroom techniques, they involved the rites of spiraling the 35mm film strips into a canister in darkness and then in the dimly lit chamber bathing the film and then the exposed photographic paper in various solutions, with the gentle sound of sloshing in cans and trays and sinks and gushing from faucets, so that the whole thing felt like alchemy and transubstantiation and mystery, and what it means to go digital, dry, and into daylight has not yet been fully explained, but it must have an impact on how artists think and see, and it all makes me think of the other liquids in visual art including clay slurry, molten metal for casting, and the squish of fresh paint carefully brushed onto the canvases of the Virgin, sloshed and poured and splashed at a certain abstract-expressionist moment that was always seen as being about the actions of the artist but was as much about the fluidity of the medium, a sea of paint hitting its canvas shores, but always left to dry so that the flow stopped and something resembling permanence or at least durability was achieved, and of course the work in this book was made by coating the paper itself in the liquid cyanide mixture in darkness and bringing it to the water’s edge to impress upon it the movement and refracting power and processes of water, liquid and frozen into crystalline formation, capturing not a split second like a snapshot but a passage of time in which the water moves or freezes into crystals, and then bringing it back for another bath, a watery process about water and in the course of so being about what water is always about when it’s liquid, namely that condition we call fluid, as in changeable, evanescent, escaping captivity, the antithesis of frozen and captured.

Ice, #6447 © Meghann Riepenhoff, from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice © Radius Books.

Ice, #6447 © Meghann Riepenhoff, from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice © Radius Books.

*

Frozen, we say, to mean that something stopped, because ice stops things, it holds things still, holds itself still so that some of the best records of the distant past we have include ice cores from Greenland whose bubbles let scientists measure the mix of gases in the ancient atmosphere, frozen bodies of ancient men and mammoths in permafrost in Siberia or ice in the Alps, frozen viruses in graves of Spanish flu victims in Alaska, and even to say “freeze” makes me think of those children’s games where someone would call out that word as a command that we were all to suddenly hold still wherever we were no matter how comic or awkward our position, and beyond that to think of the mystery of how the pure liquidity of water becomes that solid thing ice, so that in the cold places anyone can walk on water as a god is said to have strolled on the Sea of Galilee, so that a recent pastime in cold places was recording a thrown cup of hot water freezing solid before it hits the ground, rather as the water appeared to freeze in the instantaneous Muybridge photographs, how much photography has itself been considered a project of freezing the river of time, with latitude for the artists who entertain blur or capture sequence or otherwise allow not the sharp shard of an instant but a bit of the flow of time; frozen we would say for something that stopped, and thaw for a relationship restarted or repaired after a while; there is a perspective from which to argue that the liquid is free and mobile and unrestricted and thereby better than what is stilled into ice crystals, but freezing protects things, and solidity has its charms, and really life on earth is made possible by the properties of water including the temperatures at which it is liquid and gaseous and solid, and life on earth is now troubled and menaced by the circumstances we have created in which the earth warms, the ice melts, the oceans rise, the elegant synchronicity of seasons and species are warped and shattered, and both drought and flood, along with fire, do what they have not before in this era we call interglacial because it was preceded by the ice ages that packed up so much of the earth’s water in ice that shorelines were far lower than they are now, but what comes next will not be an interglacial but a further melting of ice that will change, is changing, all the shorelines again, and everything else.

____________________________

From the essay “Seven Sentences on the Frozen and the Fluid” by Rebecca Solnit from Meghann Riepenhoff: Ice from Radius Books. Co-published with Yossi Milo. Photography by Meghann Riepenhoff. Original Text by Rebecca Solnit. Used with permission of the publisher, Radius Books. Photos copyright 2023 by Meghann Riepenhoff. Text copyright 2023 by Rebecca Solnit.

Rebecca Solnit and Meghann Riepenhoff

Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of twenty-five books on feminism, environmental and urban history, popular power, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and catastrophe. She co-edited the 2023 anthology Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility. Her other books include Orwell’s Roses; Recollections of My Nonexistence; Hope in the Dark; Men Explain Things to Me; A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster; and A Field Guide to Getting Lost. A product of the California public education system from kindergarten to graduate school, she writes regularly for the Guardian, serves on the board of the climate group Oil Change International, and in 2022 launched the climate project Not Too Late (nottoolateclimate.com).

Born in Atlanta, GA, Meghann Riepenhoff is an artist based on the west coast of the United States. Her exhibitions include the High Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Denver Art Museum, the Portland Museum of Art, Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Yossi Milo Gallery, Fraenkel Gallery, Jackson Fine Art, Haines Gallery, The New York Public Library, C/O Berlin, and the Aperture Foundation, among others. Publications include ArtForum, The New York Times, Time Magazine Lightbox, The Guardian, Foam, Oprah Magazine, Harper’s Magazine, and Wired Magazine. Collections include the High Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Harvard Art Museum, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Riepenhoff has published two monographs with Radius Books and Yossi Milo Gallery: Littoral Drift + Ecotone andIce. She was an artist in residence at the Banff Centre for the Arts and the John Michael Kohler Center for the Arts, was an affiliate at the Headlands Center for the Arts, and is a Guggenheim Fellow.