I always hated “realistic” fiction. What I mean is slice–of–life type writing in which it’s just people’s feelings and observations and no one does anything, there’s no plot, no conflict. My father was a scientist, a biologist. He was a hard–working, smart person, and he came to the US on a visa for priority workers, and if he was casually sexist sometimes, it was stupid of me to get upset. For fun, he liked to read police and spy novels. They showed good action and conflict, and a good understanding of the world, crime and politics.

“It’s pure entertainment of course. But oh there’s something to it you know,” he’d tell me.

“I know. I actually agree. I’m not saying I don’t like it.”

“It shows the writer has experienced life. You wouldn’t know anything about that!”

“Hahaha,” I said. “I do know. I definitely do get it.”

I laughed to show him that I was on the same side. I knew how I looked, who I was. I wasn’t trying to fight with him or be different.

After college I wasn’t sure what to do next. I used my father’s money to start a hormone regimen and pay for masculinization surgery. My father was initially skeptical, condemning and ridiculing the decision, but, after the first few years, even he was satisfied with the physical outcome of the treatment. As part of the new sense of self I was experiencing from the male hormones, I started to get seriously involved in weightlifting. I even tried to write a short story about it to show my therapist. Though I was trying to avoid the pitfalls of “realistic” fiction, I wanted the plot of this story to reflect what I felt to be the “reality” of weightlifting: the drama of exerting yourself physically against objects, of seeing the effects of this drama on your body and others’ bodies. I tried to tie it in with the figure of my father, the way he claimed to have contempt for “aggressive” physical activity, despite his weakness for action–based movies and books.

I kept going to the weightlifting gym. When I showed my therapist the story, she said that she was “not my professor,” but that it seemed like the story was very “dense,” like I put in a lot of effort. I finished the first level of the Stronglifts 5 x 5 program.

Around this time, I went on a date with a woman. I was anxious because I had never done this prior to starting the hormone regimen, and I wondered if I would be able to have, now, a physical and emotional reaction to a person of the, now, opposite sex.

At first, it did not seem like it. Despite the physical changes that had taken place, I found myself experiencing the same interior disconnection. As I walked side–by–side with her at the art opening, through unheated rooms filled with wire, papier–mâché, plastic, and glass, I felt helpless trying to engage her in dialogue, trying to find things to say about her, me, the art, the weightlifting gym, my story about the weightlifting gym. That same humiliating, feminine instinct to please.

Afterwards we went to a bar.

“I don’t think this is working. I know I said I was bisexual,” I said — pretending to be more drunk than I was — “but I think I am actually a gay man.”

“What?” she asked, her eyes unfocused.

“I think I am gay. This is more like a friend date. Sorry.”

She moved unsteadily on the seat. She thrust her face into mine, touching the upper half of my body.

“You want to be friends??”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Are you saying you’re not attracted to me?” she said, slurring her words.

She touched my arm. With her other hand, she forced my hand under her shirt. The physical contact itself was startling, and not something I had experienced before, but the following sentences, combined with the bodily contact sensation, were what changed the evening for me.

“You said you were straight,” she said, her eyes inches from mine. “I am always alone,” she continued. “I spent so much time getting ready for this date. I thought someone like you” — she emphasized you — “would get it.”

It was at that point that I was able to connect with her on an instinctive level. The way she touched me, without regard for my subjectivity, as if I were an object, an obstacle against which to exert oneself as a result of one’s own ridiculous, feminine emotional needs, released my anxiety and triggered an elemental physical response. “It was like a weight he didn’t know he carried was lifted inside him.” A phrase from one of my father’s police novels. That was how the main character felt after he had sex with a woman.

I pressed my body against hers. “Let’s go to my apartment.”

We went to my apartment. I shared it with two other guys, trans guys. We squeezed past their bike in the hallway. I pointed out their collection of chunky, oversized sneakers and boots. In my room, the smallest in the apartment, which contained a futon and a water jug that I liked to drink from at night, we had a sexual encounter. I reenacted all the scenes I remembered from mainstream porn, until I wasn’t feeling it anymore. We talked afterward.

“It’s cool you have roommates,” she said, her eyes darting around.

I offered her a drink from the water jug. “I don’t really like them,” I told her.

“Well,” she said, tentatively touching my sculpted chest, “at least you’re not alone, right?”

I withdrew my hand. I ran it along her neck in another simulation of a porn gesture.

“I’m definitely alone all the time,” I told her.

The conversation was reminding me of how I talked to my father. And in fact, seated casually on the edge of the black futon, in the space afforded to me by her lack of awareness of me, her self–loathing, I felt for the first time that I could become my father. If this were a story, here is where the plot would be, I thought. Here would be the beginnings of conflict. I could be anyone, a policeman, a politician. Finally, I was living in reality. I was not living in a “realistic fiction” any more.

__________________________________

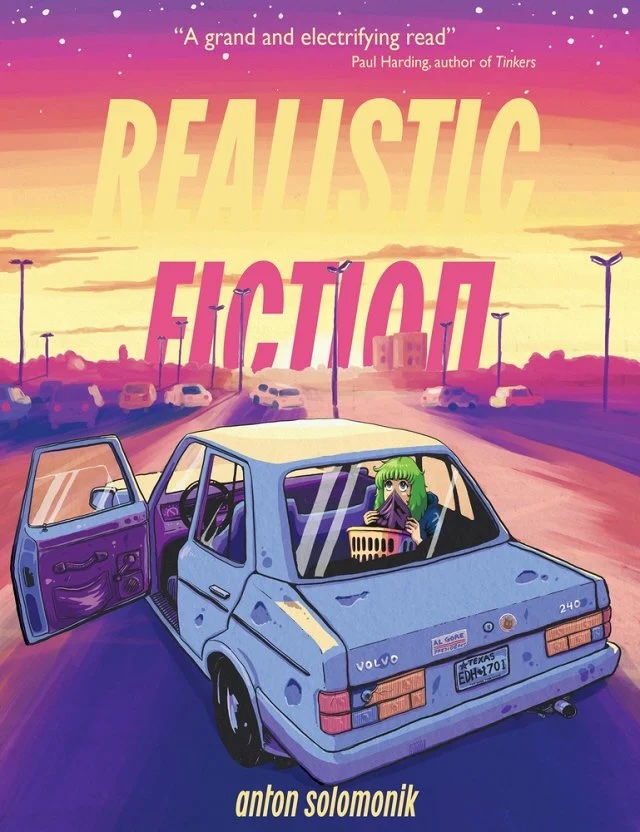

From Realistic Fiction by Anton Solomonik. Used with permission of the publisher, LittlePuss Press. Copyright © 2025 by Anton Solomonik.