Reading the Planet's Future in

Hawai‘i's April Rains

Ligaya Mishan on Facing the Climate Crisis

In the evening it started to rain, pooling in the backyard until the earth couldn’t swallow it anymore and the grass went under, a jade gleam like a rice paddy. Then it started coming in, finding the weakness under the sliding doors, seeping and spilling so gently across the white tile of the living room, almost apologetically, because it had nowhere else to go.

In Hawai‘i, it rains almost every day, but for the most part gently, at the edges of waking life, early in the morning and again at night, what the weather reporters duly describe as passing windward and mauka (mountain) showers. When it does fall during the day, you can usually see it before you feel it, dark clouds massing in a corner as the rest of the sky stays that ridiculous blue, a color impossible to prove to anyone who doesn’t live here. It can feel like rain is a place apart, with borders; you can drive out of it in a minute—walk out of it, even, by simply crossing to the sunny side of the street.

The ancient Hawaiians had more than two hundred names for rain, as documented in the book Hānau Ka Ua (2015), by Collette Leimomi Akana with Kiele Gonzalez. Among them: kili noe, misty and fine, and kili ‘ohu, mistier still; kuāua, windless; ‘awa‘awa, cold and bitter; apo pue kahi, the rain after a loved one dies. Sometimes a storm rolls through as if too busy to dally. Sometimes there are no clouds, just drops far apart and fat as tears, while the sun keeps going, untroubled, too above it all to care.

And sometimes the rain is forever and everywhere. Our house, on the eastern side of O‘ahu, had always held firm, through lashings of hurricanes with Xs of masking tape on our windows, through flash floods that swelled out of the concrete canal built to hold it in, up on the hill between Haleola and Anolani and snaking down the valley. But now the living room was breached, and my mother, who turned eighty this year, was alone; I was in New York, six hours ahead and useless. After my father died nine years ago, she said it seemed to rain harder. She’d bought a pump for the backyard, and when that gasped and failed she’d bought a second one.

The handyman who helped her around the house with leaks, jammed light switches, and obstinate appliances had just put in a new drainage system. She called him now and he promised to head out to the rescue. Ten minutes later he called back: Kalaniana‘ole Highway was a river, cars abandoned in water a foot deep, flashers pulsing. The city had shut it down. Nobody could get into the valley, or out.

She went in search of towels, stacks of them from a hoard of decades, some so brittle and stiff they seemed less likely to soak up water than to float on it. (To me, a few of them still bore a faint whiff of our dogs, long dead, who’d slept on them at night in the hall—although my mother told me that was impossible, since she’d cut up those towels for housecleaning rags long ago.) First she tried to cram them under the doors, hoping to stanch the flow, but it was insistent, biblical; so she laid them out in a patchwork on the floor. By now the water had risen over the rug, lapping the legs of the furniture. She couldn’t move any of it by herself—her hands were rigid from arthritis—so she stood on the step that marked the threshold of the room, taking stock, maybe even saying good-bye, consigning it all to rot. I’d worried about that step as my mother got older, so easy to slip and miss, but those were necessary inches now, holding the water at bay. She dried her feet, went back to the bedroom, closed the door and fell asleep. She said, “I just had to surrender.”

*

My mother is at once a worrier, which is my inheritance, and something of a fatalist—or, more precisely, she is a believer: she trusts that God will see her through. This was not her first disaster, and not even her first disaster that year. Three months before, on January 13, 2018, at 8:07 a.m., the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency had sent a statewide alert to every cell phone and TV screen, announcing an imminent ballistic missile attack: “seek immediate shelter. this is not a drill.” Tensions had been running high between the United States and North Korea, which is less than five thousand miles from Hawai‘i; from the Tongchang-ri launch site, an ICBM outfitted with a nuclear warhead could reach the islands in less than twenty minutes.

We’d always been aware of our vulnerability to the weather, attuned to the possibility of disaster.

When I was growing up during the Cold War, air-raid sirens were tested on the first working day (to me, school day) of every month. It was a distant wail so familiar I barely registered it, and only as a reminder of passing time. At some point in the nineties, the sirens stopped; perhaps everybody envisioned a world suddenly at peace. In 2017, they started again, to my Californian husband’s dismay on an otherwise serene Christmas visit. It hadn’t occurred to me to explain, or that one day the warning could be real.

At 8:45, another alert came through. The powers that be had quickly determined this was a false alarm—apparently the wrong message had been clicked on a drop-down menu—but took thirty-eight minutes to share the delightful news with everyone.

I was in New York, in my own life, ignoring the world, so by the time I heard about it, the crisis was over. My mother didn’t even call. She texted: “Missile attack siren! Early this morning. What was I supposed to do? 15 min to prepare for death?”

She never told me how she spent those thirty-eight minutes between life and death. I asked; she evaded. And when the flood came three months later, on the night of April 13, she said much the same thing, with a shrug in her voice: “I couldn’t stop it. There was nothing I could do.”

*

A few hours after the flood began, the water receded, and the rain, which had been falling at a rate of two to four inches per hour, slowed and ceased. The drowned towels were so heavy my mother couldn’t lift them; her housekeeper, who came twice a month, made an extra trip to help her hang them in the yard. She sent out the rug to be cleaned, but a stain persists, as do stray marks around the legs of chairs, like a nipping at the ankles. For days afterward, she saw waterlogged furniture dumped all along the side of the highway, and knew that she was lucky: the water in the house had run clean and left no mud. (“I didn’t even have to wash the towels,” she said.) Elsewhere on O‘ahu, there had been power outages and mudslides. The government took weeks to clear over eight hundred tons of debris. Acres of crops in Waimānalo were lost. Students were displaced from a mud-ravaged school on the makai (ocean) side of Kalaniana‘ole. My beloved ‘Āina Haina Library, where I malingered for much of my childhood, was so severely damaged it didn’t reopen for a year.

Far worse was visited on Kaua‘i, the storm’s second destination. On the island’s North Shore, 49.69 inches of rain fell in twenty-four hours, according to a gauge at Waipā Garden, which was verified by the National Climate Extremes Committee as the new record for twenty-four-hour precipitation in the United States. In total, 54.37 inches fell, most of it in three ruinous bursts: just under 20 inches in seven hours on Saturday, April 14; another 18 inches in five hours after midnight; and 8 inches in a little over two hours later that morning. People paddled surfboards down roads under six feet of water to help with evacuations. Cowboys rode Jet Skis to lasso buffalo swept into Hanalei Bay and stranded on the reef.

The farmers may have suffered most. Taro patches, representing close to 85 percent of the state’s crop, were choked with silt, making the plant’s bulbs go loliloli (spongy)—no good for poi, the sticky lilac taro paste that is a local staple, its texture measured by how many fingers you need to lift it to your lips: one finger at its thickest, three if it runs. Within a month, restaurant suppliers were complaining of shortages and likening taro to gold. It was more than that, a link to Hawai‘i’s past, before contact with the West, when the islands were self-sufficient and poi was eaten by the pound—up to fifteen pounds a day in some tales—keeping the people alive. To understand taro’s importance in Hawaiian culture, you must know that it was present at the creation: When the Sky Father’s first child was stillborn and buried, taro rose from the grave. The second child, the little one whom the elder taro had to tend and protect, was us.

*

Have the rains grown heavier since my father died? I still remember the New Year’s Eve flood of 1987, up to seventeen inches of rain in some parts of east O‘ahu, forcing the evacuation of thousands, with hundreds winding up in emergency shelters. My father recorded the aftermath with his video camera, walking the valley, panning over sideways trees and the brown torrent in the canal. He ended each clip with the old radio communication code Over, as if he were sending a message, although to whom, I’ll never know.

In the violence of that April’s rain, a number of scientists saw not an aberration, but the future.

Living on an island—on what is technically the most remote island chain on earth, more than a thousand miles from another country, more than two thousand miles from the nearest continent—we’d always been aware of our vulnerability to the weather, attuned to the possibility of disaster. Both of my parents were children during the Second World War, my father in En gland and my mother in the Philippines, and they took that memory of survival as a guide: much of the stock in our larder was in cans or powdered form. We had matches and flashlights at the ready lest a hurricane cut the power. I did not live next to a volcano, or at least not an active one, a fact I found tiring to repeat to boys at college on the mainland. (Their come-ons tended to feature either volcanoes or little grass shacks.)

But on the Big Island, Kīlauea has been in constant eruption since 1983. In April 2018, one of its craters collapsed; a billion cubic yards of lava were later expelled— enough, as noted in a report by the Hawai‘i Volcano Observatory, “to fill at least 320,000 Olympic-sized pools”—burying thirty miles of roads and more than seven hundred homes. Ash-white vog (volcanic smog) often drifts to the other islands, a veil over the sky that turns into a photo filter at dusk, bumping up the reds and golds and turning the sky bruise purple. You might have trouble breathing, but the sunsets are beautiful.

We learned about tsunamis at school, the deadliest smashing into the Big Island on April Fools’ Day in 1946. Tsunami warnings had their own siren, a long steady blare, unlike the banshee oscillation that would greet a missile. When I briefly lived in an apartment by the ocean—not quite on it, but able to see a sliver of it from the window of my tiny, makeshift bedroom, cordoned off by a curtain from the living room—I checked the tsunami evacuation zone map at the front of the phone book to see how far I’d have to run if a wave hit. (Just across Kapi‘iolani Park, it turned out.) The only tsunami watch I can recall from recent years was not long before my father died, after a magnitude 8.3 earthquake off the Kuril Islands, northeast of Hokkaido, Japan. He and my mother packed up the car and drove around the corner to the next street up, supposedly all the higher ground they needed. They parked and waited, and when they got tired of waiting, they drove home.

*

This was just the way things were, and yet. In the violence of that April’s rain, a number of scientists saw not an aberration, but the future. Temperatures are rising, as they have been all century: In May, twenty-seven record highs were set or matched across the state; in the first two and a half weeks of June, another eighteen.

The trade winds are shifting, too, northeasterly turning easterly and weaker, less effective at cooling. A warmer atmosphere means more moisture in the air, feeding clouds for future storms, and less moisture in the soil, so it dries out faster—paradoxically leading to less rain and more rain at once, longer periods of drought and more abrupt, catastrophic storms, born of “disturbances,” as the linguists of weather call them, and “increasing instability.” Sea levels are rising, which may make the tsunami evacuation zone maps moot. We’re told to expect more freakish “rain events,” more extreme weather, like the storm in February that brought waves cresting 60 feet, wind gusts up to 191 miles per hour, and snow on Maui, at an elevation of just 6,200 feet.

My mother was right. It has been raining harder.

*

Later, when we talk about the flood on the phone, she corrects me, as she’s done a hundred times: it wasn’t the living room that flooded, but the dining room—after I left home, she’d moved the dinner table so that guests could have a view of the garden, her opus of many years’ labor. But in my memory, we ate in that room only on special nights, huddled over folding TV tray tables, watching the Olympics, maybe, or Murder, She Wrote. I still come home expecting the living room, my living room, and when confronted by the new arrangement I don’t know where to sprawl or curl up with a book; the front room, theoretically the new living room, gets less light and is haunted by the specter of the upright piano in the corner. (I never practiced enough.)

I can’t seem to adapt to the new house inside the old one. And it keeps changing, like the island itself. Come December, in the car from the airport, I’m again surprised by the heights of buildings and the houses inching ever farther up the mountains, more each year, a game of Monopoly gone amok. I think, I can’t stop it: my mother’s daughter.

Even as I write this, a flash flood warning is once again in effect on O‘ahu, in June, historically a dry month. I read the news on my phone in the morning, New York time: rain falling at a rate of up to three inches per hour, the wettest June day on record, flooding, power outages, road closures, three people struck by lightning. A disturbance.

It’s too early to call my mother, and by the time I do, the rain in the valley has stopped. She is fine. It rains every day in Hawai‘i, she reminds me. Over.

__________________________________

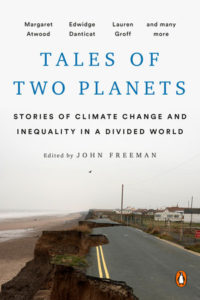

This essay appears in the anthology Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World, edited by John Freeman. Excerpted with permission from Penguin Books. All rights reserved.

Ligaya Mishan

Ligaya Mishan writes for the New York Times and T magazine. Her essays have been selected for the Best American Magazine Writing and the Best American Food Writing, and her criticism has appeared in the New York Review of Books and The New Yorker. This year she was a finalist for a National Magazine Award and a James Beard Journalism Award. The daughter of a Filipino mother and a British father, she grew up in Honolulu, Hawai’i.