Reading Myself Into, and Beyond, Pride and Prejudice

Jane Pek on the Freedom of Choice in Love and Marriage

I.

I wasn’t sold on Pride and Prejudice the first time I read it. I was seventeen, a high school student in Singapore at the cusp of the second millennium, mired in angst. I read the book because it was part of our English Lit syllabus and I had no choice. (Our teacher’s method of instruction was to screen the BBC miniseries adaptation during class time. He had a well-publicised crush on Jennifer Ehle.)

The sentences were long and opaque, strung out with em-dashes and semi-colons. The plot meandered among parlors and ballrooms and gardens, from one long-winded conversation to another. The ways that characters reacted to events and situations seemed overwrought to my callow, contemporary mindset: the fuss made over Elizabeth walking to Netherfield to check in on her sister, Darcy’s pathological abhorrence of the Bennet family, the notion that there could be no more horrific fate for a girl than to elope with a man she did not subsequently marry.

One emotional response I had no trouble at all sympathizing with, though, was Elizabeth’s horror at her best friend Charlotte deciding to marry the clergyman Collins. Setting aside how irredeemably odious Collins is—my own best friend had recently gotten into a relationship, and it devastated me. The guy was manifestly uncool: that was a universally acknowledged fact, within our hyper-judgmental teenage social circles. But the underlying cause of my misery wasn’t the conviction, as it is for Elizabeth, that this was an unsuitable match and my friend wouldn’t be happy. If anything, it was the opposite. It was unbearable to think she could find a happiness with this boy that she couldn’t with me.

At the time I didn’t dare to examine any of this; the implications—who I would be, what people would think, that I would never find anyone and die lonely—were too frightening. So I continued dating boys, and being insufferably moody. But while I had initially come at Charlotte’s marriage from Elizabeth’s point of view, it was really Charlotte’s situation that I identified with, despite myself.

One view of Charlotte’s fate is that her marriage, and the “worldly advantage” it grants her, does bring her happiness. There is a very funny line in the novel: “When Mr Collins could be forgotten, there was really a great air of comfort throughout [the house], and by Charlotte’s evident enjoyment of it, Elizabeth supposed he must be often forgotten.” But for the cost of comfort, of respectability within the strictures of your society, to be marriage to someone you could never love (let alone Collins)? I think a part of me always knew I wouldn’t be able to do that.

II.

The second time I read Pride and Prejudice I was five years older and marginally more self-aware. I was an intern at a three-person (including me) Liberal Democrat think-tank, a setup I finagled through a Yale program so I would have an excuse to spend a summer in London. (Like so many people brought up in the long shadow of colonialism—Singapore was a British colony from the 1800s to 1963—I was enamored with the culture of the conqueror.)

Reading Pride and Prejudice reminded me that we are all always in the middle of our own private narrative, moving toward a future that, by definition, we cannot know.When I’m traveling I love reading fiction that is set in the place where I am, and along with Mrs Dalloway and Down and Out in Paris and London I bought a Collected Novels of Jane Austen edition. As it turned out, reading Pride and Prejudice without the specter of having to write essays citing examples of Jane Austen’s irony and wit, or discussing the novel’s treatment of class and marriage, resulted in a finer appreciation of those topics. I like to think Austen would have approved.

That summer I fell in love with a college friend who was also in London on another program. She was from Shanghai, and possessed a kindness, and a poise, that reminded me of my high school best friend, although that only struck me afterward. I battled my growing feelings as valiantly as Darcy does his for Elizabeth, then gave up, with a mixture of relief and dread, and declared it. She was as floored as Elizabeth is by the news—not because she found me hateful, thankfully, but because, she told me, she didn’t know what to think; the possibility of such an affection had never occurred to her.

We spent two months exploring London together, the fact of how I felt resting between us like an as-yet-unRVSPed invitation to a ball. She was scheduled to leave before I was, and on her last evening we walked the city for hours, through the parks we had sat in, past the museums we had visited, along the grey length of the Thames. I asked her again, even though I suspected I knew what the answer would be. I can’t see what it would be like, she said.

I walked her to her dorm building in Bloomsbury Square and then walked back to the apartment in Clerkenwell I was sharing with three other students. I couldn’t sleep, so sat on the living room couch finishing my re-read of Pride and Prejudice, the final act when Bingley and Darcy return to Netherfield and Elizabeth is thrown into emotional tumult over whether or not Darcy is still into her. As the reader, we know she has nothing to worry about.

Of course Darcy will be steadfast; plus, as the heroine of a romantic comedy, she’ll get her happy ending. But Elizabeth has no idea—and it’s a testament to both Austen’s skill and the universality of romantic anxiety that, despite the foreordained outcome, we empathize so fully with how Elizabeth ricochets between apprehension and hope and confusion and despair and assorted combinations of all of the above, the way she overanalyzes every interaction with Darcy and each of his (inevitably brooding) expressions.

What struck me was how radical Elizabeth and Darcy are in their approach to finding a life partner.That night, reading Pride and Prejudice reminded me that we are all always in the middle of our own private narrative, moving toward a future that, by definition, we cannot know. We feel absolutely, as the present is all we have; and we’ll never have the assurance of happily ever after, unlike in fiction, but that’s because our stories don’t end, at least not until we die (which, when I was twenty-two, felt like might never happen). There was something immensely hopeful about that thought.

III.

Twelve years later I was living with my girlfriend in Brooklyn, enrolled in a fiction MFA program as a break from corporate law. Pride and Prejudice was the first title on a reading list for a class about time management in fiction. We discussed how Jane Austen both condensed and expanded time in her early-19th-century narrative about marriage in upper-class England: on one hand, breezing through swathes of time and events in summarized fashion (Charlotte’s wedding and departure from Meryton, Jane’s unfulfilling visit to London, and the closure of any budding romance between Wickham and Elizabeth all take place in the space of half a chapter!); on the other, taking us beat by beat through particular scenes such that the reader feels as if they’re right there listening to Elizabeth and Darcy argue with each other at Netherfield or encounter each other again in the gardens of Pemberley.

Meanwhile, out in 21st-century America, a revolution in the concept of marriage was taking place. The Supreme Court was hearing oral arguments in Obergefell v. Hodges, which challenged state laws prohibiting same-sex marriage. Two years ago, United States v. Windsor had struck down the provisions of the Defense of Marriage Act which denied federal recognition of same-sex marriages. All of these developments were blowing my mind.

As someone who had grown up in Asia and come of age in the nineties and early aughts, the idea of being able to marry another woman felt fantastical (and, for that matter, not a fantasy I’d ever harbored). It was only ten years before Windsor that the Court held, in Lawrence v. Texas, that laws criminalizing consensual adult same-sex sexual conduct were a violation of the individual’s right to privacy under the Fourteenth Amendment. Yet now here we were, addressing the question of whether gay couples should be entitled to participate in one of the most heteronormative institutions of all time, for their status to be recognized under law as fully equal versus a grudging we guess you’re not illegal. It felt almost like fiction, where you turned a page and leaped through time and found the universe of the novel on the cusp of change.

Reading Pride and Prejudice over the course of that momentous spring, what struck me was how radical Elizabeth and Darcy are in their approach to finding a life partner—which necessarily means, given their time, marriage. Darcy places his regard for Elizabeth above the unsuitability of her family, the opposition of Lady De Bourgh, the expectations and obligations that accompany his class and status. Elizabeth, just as radically, says hell no when he proposes, even though he checks all the ideal-husband boxes in a society where marriage is primarily viewed as an economic arrangement, a necessary means by which countless women can obtain some modicum of financial security as well as societal respect.

The gay marriage movement may be light years away from the marriages that Austen champions in her work, but it shares a fundamental contention: that individuals should have the freedom to choose who to love, and how to establish their personal happiness, in the face of custom and tradition and bigotry.

In June 2015, the Court issued its opinion for Obergefell, and my world expanded: the way it had when I realized it was possible to be both gay and happy (pun intended), and again when I met the person who became the better half of my life. But what felt equally important, and still does, is the long parallel road that gay couples walked up until that point. They formed relationships and nurtured families as meaningful as those of their straight, married counterparts—and in doing so, helped to create the space for all of us to imagine ways of loving and being together that don’t involve the sanction of institutions and the roles they make us play. There shouldn’t be any right way to conduct love. Maybe that’s the best thing about having the choice to marry: not the marriage, but the choice.

__________________________________

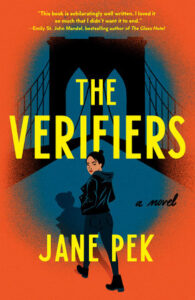

The Verifiers by Jane Pek is available via Vintage.