Reading Mahfouz: Egyptian Literature Between Old and New, Freedom and Censorship

Mohamed Shoair on the Cultural and Political Impact of Naguib Mahfouz's Children of The Alley

September 21, 1959

A sudden drop in temperature. The weather is almost cold. Autumn clouds cover Cairo’s skies. The communists are sitting in prison at al-Mahariq but the campaigns against them continue. An unknown burglar breaks into “Ibn Hani’s Vineyard” (the poet Ahmad Shawqi’s house on the banks of the Nile at Giza); among the stolen items are “a palm tree made of gold” (a gift from Bahrain’s ruler, Hamad bin ‘Isa, to Shawqi to celebrate Shawqi’s installation as “the Prince of Poets” in April 1927), as well as a silver cup from the Feminist Union headed by Hoda Shaarawi.

The newspaper headlines speak of large demonstrations in Iraq against ‘Abd al-Karim Qasim following the execution of a number of the leaders of the Shawwaf Uprising. The weekly Akhbar al-yawm leads the most violent of the attacks, vilifying Qasim as “the Nero of Baghdad.” It also publishes a piece under the title “The Accursed Book,” stating that Qasim is a follower of the ideas contained in it and claiming that the book, which attacks Islam, has been put together by Soviet intelligence sources. It then devotes a full-page spread to the popular proselytizer ‘Abd al-Razzaq Nawfal refuting its ideas.

The main photograph in almost all the papers is of Abd al-Nasser, accompanied by ‘Abd al-Hakim ‘Amir, receiving the greetings of the masses from the window of the train on which they are returning from Rashid to Cairo. Two days previously, Abd al-Nasser had delivered a speech at Rashid as part of that city’s celebrations of the victories over the British Army in 1807. The captions focus on the abolition of feudalism, the distribution of plots of land to farmers, and the launching of “Nasser’s Project for Peasant Cattle Ownership.”

At the same celebration, Abd al-Nasser handed out the prizes to the winners of the “On the Road to Freedom” competition organized by the Higher Council for Arts and Literature, in which participants had been invited to complete the short story of that name about the Battle of Rashid that Nasser had begun as a high-school student but never finished. Three hundred forty-one stories have been submitted and the Council’s Publications Committee has met fourteen times to select the three winners—Staff Officer Lt. Col. ‘Abd al-Rahim Haggag and Captains ‘Abd al-Rahman Fahmi and Faruq Hilmi. In an article titled “How to Complete the President’s Story?,” Yusuf al-Siba‘i, the council’s secretary-general, had complained at the exclusion of leading writers from the competition, resulting in a poor standard of contribution.

Reality, it appears, is always interwoven—artistically, intellectually, and politically.

The press had praised most highly the text by Haggag, even though it was the weakest artistically, perhaps because he was an officer and had used Abd al-Nasser as a character in his narrative and perhaps also because the story had been praised by Kamal al-Din Husayn, then minister of local government and president of the Higher Council for the Arts and Literature.

At the international level, the newspapers are occupied with the first visit by the Soviet leader to the USA, where Nikita Khrushchev has delivered a speech at the United Nations demanding “abolition of the armies of all the world’s states, abolition of ministries of defense and military colleges, and limiting ourselves to small units for the maintenance of internal peace.” For its part, al-Ahram maintains its coverage, which began two weeks previously, of the arrival of Russian rockets in space, thus launching a new era of science and knowledge.

A number of newspapers keep up their campaign against what they call “the disciples of James Dean,” a small group of young Egyptian admirers of the American actor (1931–55), who shot to global stardom before completing his twenty-fourth year. His performance as Jim Stark in the film Rebel Without a Cause (1955) has made him a youth icon and his shocking demise in a car accident has lent him the glamor of legend, leading young people to imitate both his looks and his clothes. The press campaign accuses the same young people of rebelling against their fathers and their generation, of performing a wanton dance called the “cha-cha,” of smoking cigarettes, and of letting their hair grow long and unkempt.

Certain preachers in the mosques accuse them of corruption and decadence, while journalists and politicians demand that they be drafted into the army, to teach them manners and make men of them. All this uproar has found a willing ear in ‘Abd al-Hakim ‘Amir, who has stepped in to deal with the phenomenon, ordering his men of the military police, in his capacity as minister of defense, to stop and shave the head of anyone whom they find dancing the cha-cha in a public place or singing ‘Abd al-Halim Hafiz’s “Abu ‘uyun jari’a” (The Boy with Bold Eyes).

In al-Akhbar, Nasir al-Din al-Nashashibi interviews Prof. Sten Friberg, a member of the administrative committee of the Nobel Prize in Literature, who pronounces that “it is the fault of the Arab universities that no Arab has been nominated for the Nobel Prize,” while Ahmad Baha’ al-Din writes from Stockholm about Jean-Paul Sartre’s play The Condemned of Altona, which he regards as “the most significant work of literature since the end of the World War.”

In Cairo, the National Theater is presenting al-‘Ashara al-tayyiba (The Lucky Card) and the Rihani troupe’s Hikayat kull yawm (An Everyday Story). The Kitabi (My Book) series is issuing an Arabic translation of Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago in two parts, and the series Maktabat al-funun al-diramiya (The Library of the Dramatic Arts) a translation of Tennessee Williams’s play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, while Riyad al-Sunbati has just finished setting to music “al-Hubb kida” (That’s the Way Love Is), with which Umm Kulthum is about to open her new season.

The cinemas are full, with posters for new films taking up much of the advertising space in the newspapers, and on that one day we can watch more than fifteen foreign films, including Sophia Loren’s The Millionairess, Bob Hope’s and Jane Russell’s The Paleface, and Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, as well as approximately the same number of Egyptian movies, including ‘Ashat li-l-hubb (She Lived for Love) with Zubayda Sarwat, al-Hubb al-akhir (The Last Love) with Hind Rustum and Ahmad Mahir, and Isma‘il Yasin’s al-Bulis al-sirri (The Secret Police).

On that same day, al-Ahram newspaper began publication, on page 10, of the first installment of Naguib Mahfouz’s new novel Awlad haratina (Children of the Alley), an event announced on its front page a week earlier:

Al-Ahram has agreed with the great writer Naguib Mahfouz to publish his new long work, in installments. Mahfouz is a writer who has proved himself capable of portraying Egyptian life with the hand of a creative and highly gifted artist; thus the appearance of a new work by him has always been a literary event of outstanding importance for the history of the intellectual revival of recent years. Al-Ahram has signed a contract for one thousand pounds with Naguib Mahfouz granting it the right to publish his new story in its newspaper. Al-Ahram does not mention this sum—the largest paid for a single story in the history of the Arabic press—out of pride or presumption but to mark the start of a new era of appreciation for literary production.

The large sum was not the only form in which al-Ahram’s celebration of Naguib Mahfouz manifested itself. The newspaper prepared for the event with what amounted to a publicity campaign, starting four days before publication with a long interview with the author by Inji Rushdi in which he spoke at length of his creative worlds, his experiences, his study of philosophy, and his love of music, and alluded briefly to the new novel. And one day before, the following news item appeared: “Naguib Mahfouz in al-Ahram Tomorrow,” accompanied by two portraits, one of Mahfouz and one of the painter al-Husayn Fawzi, who had drawn illustrations depicting the novel’s characters.

Reality, it appears, is always interwoven—artistically, intellectually, and politically. Naguib Mahfouz was writing the screenplay for Ihna al-talamza (We the Students), based on a story by Tawfiq Salih and Kamil Yusuf. Publicity for the film (starring Omar Sharif, Shukri Sirhan, Yusuf Fakhr al-Din, and Karioka) focused on its being “a film for every young man and every young woman, every father and every mother, every family and every household, a film that combats effeminacy and calls for strength and positivity!” according to a sentence written in large letters on the poster and which would seem to be an extension of the campaign to discipline “the disciples of James Dean.”

Mahfouz poses questions about the limits of truth and fiction, death and life, sanity and madness.

People who knew Naguib Mahfouz and the ways of the cinema world thought it likely that the sentence had less to do with Mahfouz than with the producer, Hilmi Rafla, who spoke of the film, in the magazine al-Jil (The Generation), as part of a mission “against the likes of James Dean, the manifestations of whose effeminacy have multiplied and the instances of whose perverseness have become so widespread that they have resulted in the intervention of the morals police, now that sexual frustration has driven these persons down the path of pain, the path of evil!” Rafla stated that he had chosen Naguib Mahfouz to write the screenplay because “he is known for the profundity with which he studies situations, the power with which he portrays characters, and the brilliance with which he gives expression to feelings and reactions.”

Mahfouz was also writing the storyline for Bayna al-sama’ wa-l-ard (Between Heaven and Earth), a film produced by Salah Abu Yusuf that appeared in theaters simultaneously with the publication of Children of the Alley and that marks a shift in Mahfouz’s cinema work away from realism and toward an openness to the symbol, just as in Children of the Alley, where he abandons the “naked realism” that had reached its apogee with al-Thulathiya: Bayn al-qasrayn, Qasr al-shawq, and al-Sukkariya (The Cairo Trilogy: Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, and Sugar Street). The film poses philosophical questions whose answers divide, multiply, and are left hanging—like its heroes in their broken elevator—between heaven and earth.

Mahfouz’s thumbprint as scriptwriter, and one seeking creative solutions to the restrictions on the space available to him in the film, is clear. It was an artistic dilemma that Mahfouz had already succeeded in overcoming as a novelist. Indeed, he had excelled at exploiting it for his dramatic purposes in both Zuqaq al-midaq (Midaq Alley), a novel whose events take place in a narrow alley, and in Tharthara fawq al-Nil (Adrift on the Nile), most of whose action occurs on a houseboat on the Nile. Throughout Bayna al-sama’ wa-l-ard, and despite the restricted space (out of which, even so, emerge worlds pulsing with life), Mahfouz poses questions about the limits of truth and fiction, death and life, sanity and madness, reality and the cinema.

On release, the film met with little acclaim from either the critics or the public; years later Mahfouz explained its failure by saying that it was “an experiment in terms of the Egyptian cinema of the time, and its success may have come after the premiere. People weren’t used to that kind of film.” Referring to the source of his inspiration for this important experiment, he added, “They had made a film of the same type in America that was meant to be a nod to Hitler. Its hero tyrannizes people in a closed apartment, and the film did very well in the West.”

Some months previously, Salah al-Bitar, minister of culture and national guidance of the central government of the Egyptian–Syrian union (at the time, Sarwat ‘Ukasha was the minister in the Southern Regional, that is, Egyptian, government) had made a statement that had set literary circles in an uproar. The minister had said that “our literature does not sufficiently express the Arab-nationalist aspirations of the Arabs.” When al-Gumhuriya (The Republic) newspaper confronted the world of literature with the minister’s words, Naguib Mahfouz commented that “the movement for the revitalization of the Arab literary legacy and its study according to new programmatic principles, as undertaken by Taha Hussein, al-‘Aqqad, and others, is a part of the Arab Nationalist intellectual project.

At the same time, any literature that is not actually against Arab unity must be counted as being for it.” Strangely, the poet Ahmad ‘Abd al-Mu‘ti Higazi, in his comment, adopted a similar position to al-Bitar’s, considering that “the men of letters of the Southern Region [Egypt] are the Arab literary figures most accepted by and best known to the Arab masses. Despite this, they have fallen short in giving expression to the broad aspirations with which the emotional life of those masses pulses.” Higazi poured scorn on the excuses put forward by other writers (Naguib Mahfouz, Yusuf Idris, Yusuf al-Siba‘i, Amin Yusuf Ghurab, ‘Ali Ahmad Ba Kathir) in response to al-Gumhuriya’s investigation and called for “workshops to be held for the writers of the Northern and Southern regions at which Arab Nationalist ideas could be expounded and promoted,” going on to recommend

the conversion of the National Unity committees into cultural and intellectual schools where the People could be educated in the truth of the Nationalist creed, a creed that President Gamal Abd al-Nasser had been the first politician and intellectual to place, with great firmness and faith, before the Arab People in Egypt, it being the duty of youth to follow the path set by their leader until such time as it becomes a living reality and the very breath of every citizen.

At this point, according to the minister, the man of letters would find himself propelled, without volition on his part, to give it expression.

__________________________________

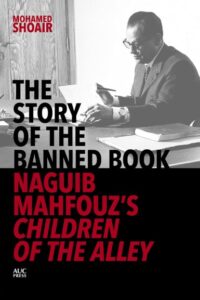

Excerpted from The Story of the Banned Book: Naguib Mahfouz’s Children Of The Alley by Mohamed Shoair, translated by Humphrey Davies. Copyright © 2022. Available from AUC Press.

Mohamed Shoair

Mohamed Shoair is an Egyptian critic and journalist, and managing editor of the literary magazine Akhbar al-adab. Born in 1974, he studied English literature at South Valley University in Qena, Egypt. He is the winner of numerous awards, including the Dubai Prize for Journalism. Naguib Mahfouz and the Story of the Banned Book won the Sawiris Prize for Literary Criticism and was longlisted for the Sheikh Zayed Book Award.