Read These 10 Books That Actually Scared Us... If You Dare

? ? ? ?

Spooky Season Recommendations from the Lit Hub Staff

? ? ? ?

Goblins, ghouls, dead plants, pumpkin spice lattes, politicians in your inbox. Yep, it’s spooky season, and the perfect time of year to read something scary—but as you know, horror can come from some unexpected places. Sure, you could go read Frankenstein this All Hallows’ Eve, and while it’s still great, it probably won’t make you jump. The following books, on the other hand, just might. Here are the books that actually scared the Lit Hub staff, this year and in years past—pick them up if you dare, but leave some space in your freezer just in case.

*

Susanna Moore, In the Cut

I do not enjoy horror. Look, life is hard enough—why would I go out of my way to have more negative feelings? I know some people find it cathartic, but I just find it unpleasant. When we were in college, my best friend convinced me to go see a movie because it was a “cool indie comedy” and it turned out to be Hard Candy, in which a pedophile and a teenager meet and one of them tortures and humiliates the other in a way that is kind of brilliant in retrospect but also deeply awful and disturbing to watch.

I tease her about it all the time, but I still fell for it when she recommended that I read Susanna Moore’s “cool feminist thriller” In the Cut, which turned out to be a terrifying, upsetting, gut-punch of a book with a devastating ending that I will not give away. In fact, if you haven’t read it, I don’t want to say anything else about it, except that you should only attempt if you have a stronger stomach than I. No doubt the novel is a triumphant work of art, and indeed a cool feminist thriller, but it is one that haunts my dreams. In a bad way. Leave me alone, Bri!

–Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Joyce Carol Oates, “Zombie”

I’m not going to watch the Jeffrey Dahmer show. I’m sure it’s entertaining, but I’m not going to watch it. It’s not that I don’t understand the public fascination with serial killers and America’s storied serial killer heyday. I very much enjoyed Mindhunter and The Silence of the Lambs and Hannibal (both the show and the extremely stupid movie). I loved David Fincher’s Zodiac. Serial killers, their origin stories, and the mark they’ve left on this country’s collective psyche, are interesting; let’s not pretend otherwise. But I’m not going to watch Ryan Murphy’s cannibal show. The center of the cannibalism/sexual violence/obnoxious theater kid pep Venn diagram is not a place I want to dwell. Ever. The barrage of ads for Dahmer did, however, pique my interest in fictional representations of the Milwaukee Monster, who committed the murder and dismemberment of seventeen men and boys between 1978 and 1991.

So, on the recommendation of a friend, I decided to go down a more literary route and listen to Akil Sharma read Joyce Carol Oates’ 1994 short story “Zombie” on the New Yorker Fiction Podcast. This was a mistake. “Zombie,” which Oates later expanded into a novella, is told from the perspective of a college-aged, Dahmer-esque psychopath who performs lobotomies on kidnapped young men in an attempt to create a docile sexual slave. It’s a horrific, deeply unpleasant story, made even more chilling by the steady cadence of Sharma’s voice. I listened to it while taking my dog for a nighttime walk in the park near my home in Wyoming. It was a moonless night in late September. There was nobody around. I should have been concerned about bull moose and bears. I was not.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor in Chief

Cormac McCarthy, The Road

The fact that The Road is the scariest book I’ve ever read has more to do with the circumstances in which I read it than the book itself. Yes, a post-apocalyptic no man’s land where cannibalism is rampant and a father must protect his son as they navigate last vestiges of humanity is terrifying—but try reading McCarthy’s bleak, pared-down prose in a dark, empty coat-check room of a Dublin nightclub in from the hours of 10 pm to 3 am, startled every few minutes to collect coats from hollow-eyed twenty-somethings. Later, I walked home through the city’s abandoned streets, a ghost town quite possibly populated by cannibalistic monsters following me back to my apartment.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

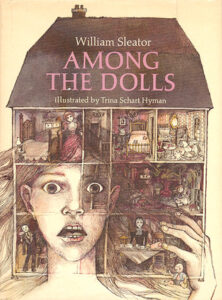

William Sleator, Among the Dolls

To begin with, as a child, I found this book in a piano bench, in a pile of loose sheet music. I’m not sure how it ended up there, but I have to assume that some other kid was so terrified of its grotesque illustrations that they hid it in the darkest place they could find. Naturally, I read it, over and over, fascinated by the story—unrelenting even by adult standards—of Vicky, a girl whose home life grows increasingly dysfunctional as she acts out scenes of familial discord with the dolls in her much-loathed dollhouse. The house—populated by a mismatched family of extremely creepy dolls—was an unwelcome birthday gift, as Vicky had requested a ten-speed bike. As if that weren’t horror enough, Vicky ends up trapped in the dollhouse, at the mercy of the dolls she’d tormented. Think Toy Story, with vastly increased accountability and trauma. Spooky!

–Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

Muriel Spark, Memento Mori

Imagine this: you’re old. And the telephone rings. And it’s a voice you don’t recognize. And it’s the 1950s, so there was no caller ID. And the voice you don’t recognize says: “Remember you must die.” And then it’s revealed that all of your friends are also getting these calls. How peculiar! What’s more: you all seem to disagree on the voice. Some of you think it’s an old man, some hear it as teasingly young. One person thinks the voice has an accent; another person hears it as a woman. The police can’t trace the calls. There is nothing to be done. And then, one by one, everyone seems to unravel in one way or another.

Secret affairs—secret marriages, even!—see the light of day. There’s blackmail and threats of poison. Someone dies of natural causes. Someone survives a stroke that leaves them senile. Someone goes mad. What’s going on here, anyway? And who was the voice on the telephone? Some friends believe it to be Death himself. But what’s perhaps even more bone-chilling than Death ringing you up to remind you of your mortality is the idea that you never really know anyone in this life.

–Katie Yee, Associate Editor

Peter Benchley, Jaws

When I read Jaws, my fear of sharks had a life of its own. Passed down from my parents’ trauma of seeing the movie as kids, the ocean was always tinged with the phantom shark that lurked below my frail, preteen body. The Fear was, and is, an obsession, so in a mad attempt to quench my curiosity, I bought and read Jaws one summer weekend, while visiting my grandparents in Northern Maine. What a mistake. Any glimmer of the life I had once lived was gone. Morning swim with my sister? Insanity. Dip in the pool? Careless. Afternoon boat ride? Horrifying. The hull of a motorboat seemed as flimsy, and bite-able, as flesh. Bathtubs, toilets, even a hefty puddle could evoke the image of those rows of teeth and a shiver down my back. I was haunted by the inflatable, overly-detailed, shark floats that bobbed in my grandparents’ pool. Seven years later, I still only swim in the shallow end.

–Eloise King-Clements, Contributing Editor

Tove Ditlevsen, tr. Michael Favala Goldman, Dependency

This book is a masterpiece; it’s also the most singularly disturbing piece of writing I’ve ever read. It feels strange and static to list the details of its history, but they matter—Dependency is the final book of The Copenhagen Trilogy, a trio of memoirs that follow Tove Ditlevsen’s working-class childhood and young adulthood as she begins a career in literature, the first two volumes of which were translated by Tiina Nunnally. Michael Favala Goldman translated Dependency, which was published in English for the first time this year as part of the full trilogy.

It opens as Ditlevsen is gaining more recognition as a writer and portrays her entanglements with several men, including, eventually, a doctor named Carl, whose dark presence drives the second half of the book. From there, Ditlevsen’s voice grows dreamlike and detached as Carl entraps her in a years-long cycle of drug addiction and violence. She narrates it all with astounding clarity: the torture of confinement with a controlling and mentally ill partner; the strange combination of hyperactivity and hazy unreality that defines her days; the dissonance of the hell inside her home and the normal, ongoing world outside of it. I can’t say I’m sorry to have read Dependency, but there are parts of it I wish I didn’t understand, and I suspect that many people, reading this book, feel the same.

–Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Connie Willis, Doomsday Book

As a certified Big Baby, I don’t consume much scary content. However, I am the specific type of masochist who will read pandemic books whilst living through a pandemic, which is how I found my way to Connie Willis’s Hugo and Nebula Award-winning Doomsday Book (1992). Here’s the premise: In 2054 Oxford, historians have tapped into time travel to enhance their scholarly endeavors. Kivrin, a young historian, begs for (and reluctantly receives) permission to travel back to 1320 Oxford to study something or other about the Middle Ages, where she immediately falls into a feverish delirium.

Meanwhile, present-day Oxford is struck with a highly fatal flu pandemic. The powers that be suspend time travel operations, sealing Kivrin in the past—only, oops, she’s in 1348 England, during the Black Death. The chapters flip back and forth between one plague and the other; life is lost, despair prevails. Willis doesn’t spare her readers from the utter devastation of pandemics… which might be too real for most readers in 2022, but hey, you asked.

–Eliza Smith, Special Topics Editor

Tana French, Broken Harbor

Tana French is the master of the slow build, the quiet suspense, the minutia of life and thought that occurs around a mystery: usually a murder in a closed-setting location, where the town is small, but everyone is a suspect. These books are meticulous character and town studies, and usually delve deep into a specific cultural facet of Ireland that French deems worthy of excavation. She’s always right: they’re immersive and captivating, but I would never call these books scary, as a whole. The anomaly of the bunch is Broken Harbor, the fourth book in the Dublin Murder series. The word scary is even up for debate: do I mean disturbing? Deeply distressing?

The difference between this and the others in the series is that rather than the traditional cause, effect, and clean solution that one typically expects in a murder mystery, this book is about something more insidious, and ultimately scary in its unpredictability: madness. The Spain family moves to a new housing development that promises the suburban dream: happy kids biking through the streets, cookouts with the neighbors, and a giant return on the investment of a lifetime, only for the development to halt construction midway through, though firmly after the Spains have already sunk their savings into a house that will never offer a return. This financial decision upends the family’s status quo and sets the ball rolling steadily downhill. Worse and worse things befall the Spains, and the family enters into both economic and psychological ruin. What makes this story so affectingly terrifying is the sheer possibility of it, how life can turn on a dime (or a huge down payment). It reveals the fine balance one’s stability is hanging upon, especially for men in traditional communities who can predominately bear the weight of “providing” for a family, and the violence that can occur in the wake of male failure.

–Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Agota Kristof, tr. Alan Sheridan, The Notebook

The first of Agota Kristof’s harrowing trilogy of mid-century morality fables, The Notebook tells the story of twin boys adrift in the borderlands of Mitteleuropa as the last cruel seasons of WWII bring suffering to nearly every living creature. The boys—no older than ten—have little to no supervision and wander around like tow-headed aliens performing depraved grad school experiments on the adults around them, all of whom have been driven to desperation by the horrors of war. Peeing on a sadomasochistic Nazi? At his request? Check. Blowing up a malicious housekeeper who taunts a starving Jew on the way to a concentration camp? Yup. Poisoning grandma? Sure thing.

Look, if weird little amorally monstrous children aren’t scary enough for you, how about a chilling reminder that the membrane between “civility” and “depravity” tears far easier than we think? Indeed, perhaps the scariest thing about The Notebook is the way its fictionalizing of our darkest histories suggests how fragile our futures really are.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.