Ray Bradbury Understood the Narrative Power of Tattoos

Anna Felicity Friedman on Body Art

It was a rainy, summer day in the late 1980s, long before smart phones kept us incessantly occupied, when I climbed three flights of stairs to a little-used attic room in the rambling house in which I grew up. This room, paneled floor to ceiling with cozy, pine beadboard, was a catch-all of sorts. Among the odds and ends cluttering the floor, usually forgotten bookshelves filled with dusty old paperbacks usually beckoned me.

Bored, and looking for something in which to immerse my mind, I scanned the shelves for a new read. As a bookwormy teen, I had previously found some gems among overly erudite tomes and stodgy classics: racy novels, thought-provoking poetry, formative philosophy, and on this day . . . Ray Bradbury’s collection of short stories, The Illustrated Man.

I was into punk and weirdness, but tattoos were still unusual when I was in high school. My friends and I would read to tatters copies of the only widely circulated tattoo magazines in production then, Outlaw Biker Tattoo Revue and Tattoo, which we could only find in the city—not our sleepy suburban bedroom community. In those magazines, I saw a vision of my future heavily tattooed self, permanently positioned on the fringes of society through my bodily adornments.

But a magazine can only take the imagination so far. Bradbury’s frame story “Illustrated Man” offered me a mesmerizing character to ponder. What stories might my future tattoos tell to others?

Tattoos and perceptions of them have transformed enormously from 1950–51 when Esquire first published Bradbury’s short story in July of 1950, followed by the author using the character again as a frame device for the prologue and epilogue to The Illustrated Man collection. Tattooing was mired in a dark time in its history then, perhaps at its lowest point of popularity in modern times.

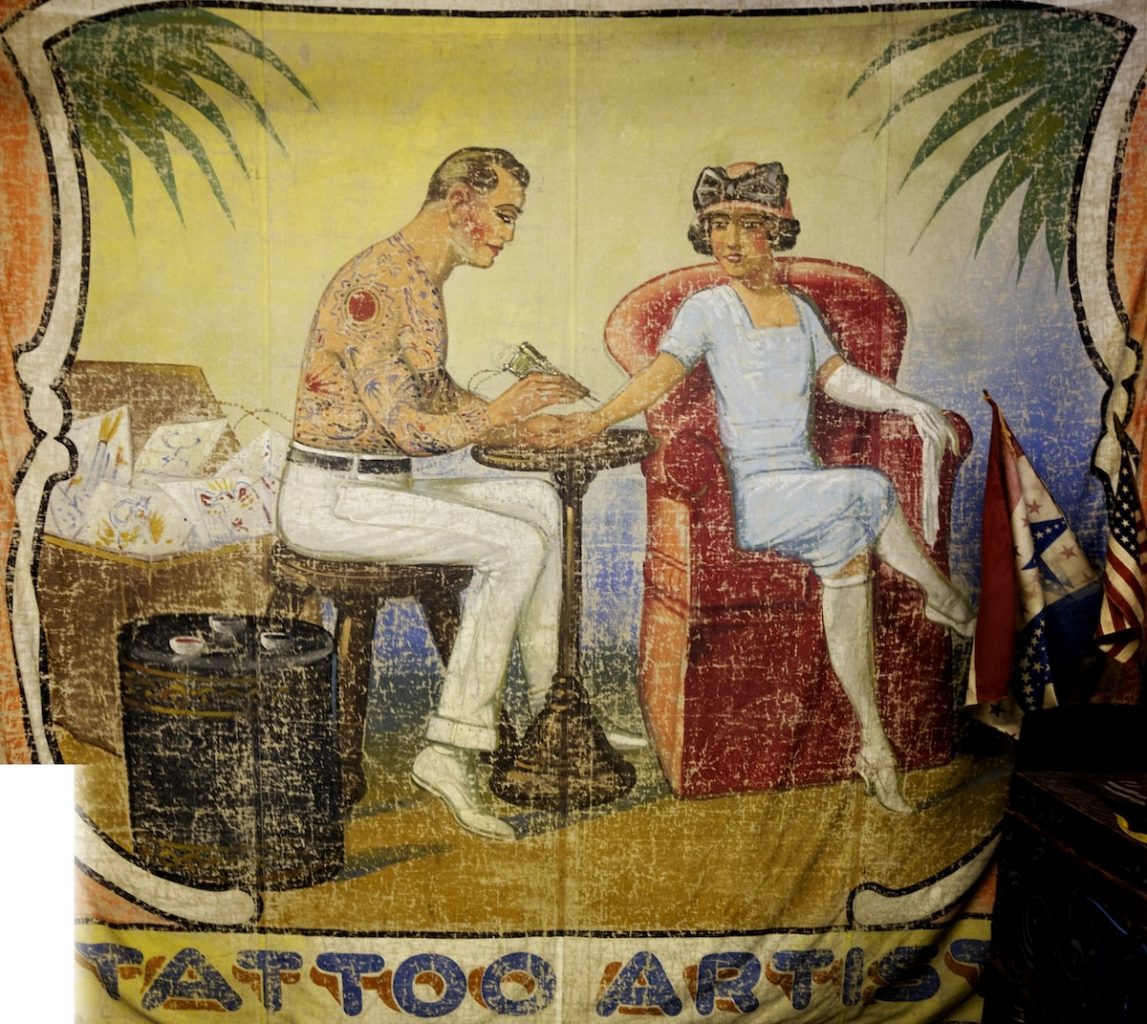

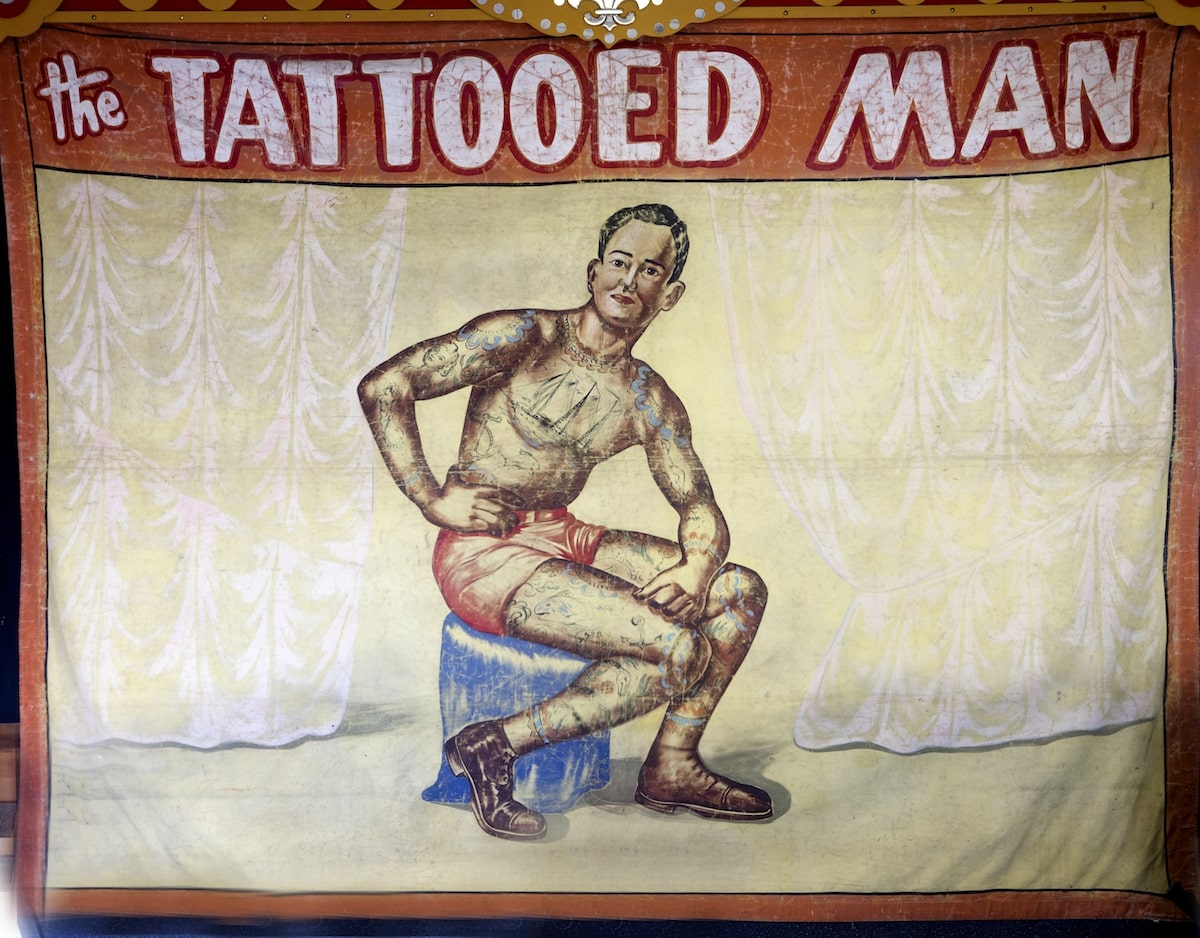

The heyday of the circus sideshow had passed, tattooing was mainly relegated to skid-row areas and near military bases, and, aside from macho characters like the soon-to-be-conceived Marlboro Man, tattoos were not for everyday people. By the 1950s, tattooed men held little appeal—especially compared to tattooed ladies—and Bradbury masterfully captured the pathos of being a washed-up tattoo performer, despite still being an extraordinary work of art, in his portrayals of Mr. William Philippus Phelps.

Tattoos can communicate compelling narrative, evoke strong emotion, conjure fantasy, or merely just dazzle with aesthetic wonder.

Earlier, in the 1930s, when Bradbury first encountered circus and sideshow performers, tattoos were special. Tattooed attractions, particularly women, enjoyed celebrity. Roaring ’20s adventure stories, mysteries, and romance novels with tattooed characters, like Howard Pease’s The Tattooed Man, which first appeared in 1926 and which Bradbury is known to have read, enjoyed widespread popularity.

Albert Parry, author of Tattoo: Secrets of a Strange Art (one of the few book-length investigations of tattooing in the early to mid-20th century), estimated that at the time of publication in 1933, there were approximately 300 “completely tattooed men and women in this country, making, or trying to make, a living by exhibiting themselves.” This desirability to be a star, countered by how fleeting such fame could be, manifests in Bradbury’s unfolding of the story behind Emma Fleet’s tattoos—that her husband’s love for her will wane if she can’t grow more canvas.

While there have always been heavily tattooed men and women, here you can see how far extensive tattooing has evolved in the present day. As “Windows looking in upon fiery reality,” Bradbury writes in the prologue, tattoos can communicate compelling narrative, evoke strong emotion, conjure fantasy, or merely just dazzle with aesthetic wonder. In the 21st century, tattoos may finally have carved themselves a solid niche in human expression that may withstand the ebbs and flows of historical opinion.

To read Bradbury’s three tattooed-person tales embedded within this glorious parade of contemporary inked bodies breathes new life into his notions about how tattoo meanings can change, how the viewer of a tattoo can see something different than what the owner might have intended, and how psychology intersects with the desire to permanently inscribe one’s skin.

I crept back down the stairs, fantasizing about the embellishments I wanted to get. Tattoos were illegal in my home state of Massachusetts, necessitating travel to neighboring New Hampshire to the biker shops that did brisk business on weekends serving out-of-towners. I couldn’t wait until I met the age minimum of 18 to become permanently marked as an outsider, as a creative soul, as an iconoclast.

Shortly after that first tattoo pilgrimage, before my 21st birthday, I became one of only a few hundred women in America with full tattooed sleeves. Little did I know that only a decade later, I’d be trendy, an early adopter of large-scale tattoos that would overtake mainstream culture as a coveted accessory, a mark of prestige, a desired vogue. If I could travel back in time, I might choose different tattoos given what is possible today. Yet gazing at weathered, inked skin—witness to pain, delight, and everything in between—offers comfort.

Will the future hold Bradbury-esque tattoos that can transform at the whim of their owners? A wistful day might offer a window into past nostalgia, a challenging stretch could summon visual armor, a joyful time would explode into vibrant ornamentation . . .

__________________________________

From the introduction to All Of Me Is Illustrated. Used with the permission of the publisher, Lawrence Schiller. Introduction copyright © 2020 by Anna Felicity Friedman.

Anna Felicity Friedman

Interdisciplinary scholar Anna Felicity Friedman has researched the history of tattooing for nearly thirty years. A collector of tattoos since 1990, Friedman writes and lectures widely about the art form, and is the author of The World Atlas of Tattoo.