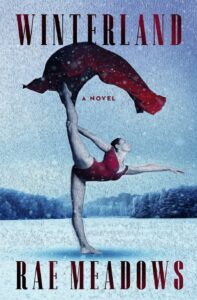

Rae Meadows on Immersing Herself in the World of Soviet Gymnastics

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Winterland

Within a few pages, Rae Meadows’ fifth novel, Winterland, immerses readers in the birthplace of an aspiring Soviet gymnast Anya Petrova, who we meet at age eight in 1973, the Golden Age of her country’s gymnastics (the Soviet team dominated eight consecutive Olympics). The closed Arctic city of Norilsk, built by gulag labor, is the world’s northernmost city, a center for mining nickel, copper, platinum, cobalt, and other minerals. It’s a land of polar winter, when the sun doesn’t rise for two months. Like the weather, the pollution is extreme.

“The rain burned her skin, the fog made her throat itch, and the air made her cough,” writes Meadows. “The snow blew gray and sharp like tiny nails.” Anya is being raised by a single father, once a gymnast himself, after her mother, a Bolshoi principal dancer, disappears. No wonder she is driven to success as a gymnast. When she is accepted into the training center in Moscow, she is convinced she now has “the glittering key that would unlock a world that most people could never know. What it felt like to fly. Gymnastics would turn her into herself.”

Her journey is grueling and enlightening, ultimately encompassing three generations, multiple continents, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the growth of Russian immigrant communities in Brooklyn. As darkness and icy chill descend on the Northern Hemisphere, and Russia continues to weaponize winter in its war against Ukraine, Winterland is an eerily timely read.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have you managed your life and work during this past few years of uncertainty and turmoil?

Rae Meadows: Being a writer is being used to being a recluse, so for a while lockdown wasn’t so bad! But I didn’t get much work done—our apartment turned into a gym with a beam, air track, and even a bar. I will say the political moment has felt very destabilizing, and my attention span has been spotty. I actually think writing about the eerie and repressive life in the Soviet Union was an apt project for these years.

JC: What inspired you to write a novel about the Olympic champion Soviet gymnasts in the 1970s, the era of transition between Ludmilla Tourischeva (“she was pretty, like a film actress, her dark hair styled in a smooth sweep, her tall curvy body graceful and dramatic”) and newcomer Olga Korbut (“small and flat-chested, with a lopsided grin and messy pigtails adored with loopy yarn bows…whipping her body through the air, flitting with audacity”) and the rise of the upstart Romanian Nadia Comaneci?

RM: As a child I watched this new generation of Soviet and Romanian gymnasts on TV and they were tiny, graceful, and electric, with these serious faces, and I was in awe of them. (At the time American gymnasts were nowhere near their level.) The state training system was brutal, but such beauty came out of it, and I wanted to explore that dynamic, as well as the costs of greatness. It was also a perfect excuse to lose myself in watching gymnastics under the guise of research.

There is darkness in many forms in the book, and I think the landscape helped heighten this mood.

JC: Why set your story in the Arctic copper-mining town of Norilsk, with its dark winters and polluted air? How does that location and its history shape your story?

RM: I am drawn to inhospitable landscapes—my last novel was set in the dust bowl!—and I find it fascinating how human beings adapt. In some ways it was easier for me to imagine a fictional world in Norilsk because it is so extreme in its temperature and light, isolated even from the Soviet Union itself. (Norilsk is still a closed city, which means one needs permission from the Russian government to visit.) You can’t write about the Soviet Union without including the Gulag, and Norilsk, because it was built by forced labor, made it easier to include this history. There is darkness in many forms in the book, and I think the landscape helped heighten this mood.

JC: What sort of research was involved in creating such vivid details throughout—the demanding training, the Cold War aspects of the power structure within the athletic world, the submission, at times physical abuse of the young gymnasts, the performance circuit, the sad decline of so many. What makes you understand gymnastics? (Do you do gymnastics yourself?)

RM: Research was everything for this novel, and I loved it. I read widely about the Soviet Union, pre-revolutionary Russia, the Gulag, sports in the USSR, and gymnastics, and watched hours of film of the Soviet gymnasts, both competitions and training. I was a gymnast as a child, my daughter is a competitive gymnast, and I returned to gymnastics in my forties—it’s definitely an obsession! I think understanding—and loving—gymnastics was essential to portraying the physical and mental challenges for Anya in the novel. It seems really difficult to imagine depicting the physicality of gymnastics skills if you’d never tumbled or swung bars.

JC: Anya Petrova is an unforgettable character from the time we meet her as a child, living with her father in northern Siberia, sadly without her mother Katerina, a Bolshoi ballerina who had danced for Stalin at fourteen and then run afoul of the Party. Katerina had gone missing several years before. At eight, Anya is beginning to feel the hunger that is the foundation for greatness in sport. “Anya’s focus never wavered, even when her legs noodled from exhaustion. It was more than a goal. It was a vision. A bright burning spot that eclipsed, for the time being, that ever-shifting feeling of unease she carried in her core.” How did you develop this character?

RM: Anya is not based on my younger daughter, but because she is close in age to Anya and also a serious gymnast, I was able to see gymnastics through her. Anya seems older than her years in some ways because she has lost her mother, and her father is often an ineffectual parent. Her motherlessness, that loss, is part of what drives her to push further in gymnastics. Anya is at the mercy of all of these external forces—her coach, the state system, the Soviet Union—but her core, her sense of self, is her own, and I think this ever-shifting dynamic was a great guide for developing her character.

JC: You write of other aspiring gymnasts like Anya’s classmate Sveta, equally talented, who doesn’t make the Moscow training team, and Elena, based on Elena Mukhina, whose imagined rise to Olympic glory was cut short by a tragic accident. Their stories, and Anya’s, make clear what a brutal sport Soviet gymnastics could be, and also how dire the alternative can be for youngsters like Sveta.

RM: Sveta is a stark example of the inequities of Soviet life, and Elena, the danger of being pushed beyond her physical limits. Both are reminders of what a precarious position Anya is in. She knows she is lucky to have been chosen—the honor, the money her father gets, the chance to devote herself to what she loves—and at the same time, she learns early on that she cannot say no to her coach, and that her body, her life, is in someone else’s hands. Her fate is a high-wire balance.

JC: Anya’s father Yuri is a pyrometallurgist whose prominent status with the local Executive Committee was withdrawn because of his wife Katerina’s political missteps. How did you develop your sense of the layers of power at work in the Soviet system? Anya’s future can be a way for her to rise above her father’s status, correct?

I think there is a novelist’s longing to know what becomes of a character.

RM: It’s easy to see the difficulty, unfairness, and hardship of life in the Soviet Union, but I wanted to show the other side as well, the optimism of the full-hearted believers. When we meet Yuri in the novel, he is trying to hold on to his faith in communism and the Soviet experiment, despite having slipped in its ranks. He likes that Anya reflects well on him and sees gymnastics as a way for her to both serve her country and have status in the eyes of the party, even while knowing the system is why his wife may have disappeared. Yuri embodies many contradictions, still hoping that communism is “right.”

JC: Characters like Yuri’s neighbors Vera, in her 70s, who spent ten years in a gulag prison camp near Norilsk, and Ledorsky, who knew her there (and who has a polar bear cub in his apartment), show us how an earlier generation under Stalin. How did you research their lives?

RM: Elena Chernyshova took a series of photographs of Norilsk, which I found inspiring and haunting. One of the photos is of an old woman, and the caption notes that she spent ten years in a Gulag camp. It made me wonder why she had stayed in Norilsk, and that question became the spark of Vera’s character. I wanted Vera to be old enough to remember an upper-class life before the Revolution as a counterpoint to her experience in the camp.

The generation under Stalin did not often talk about the camps for many reasons including shame, though now their stories are out there. (It’s always worth noting two tremendous books: Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time, and Anne Applebaum’s Gulag.) With estimates of 15 million people passing through the Gulag system, this history is essential to understanding the Soviet ethos.

JC: Why did you decide to move the story forward into Brooklyn circa 1998?

RM: I live in Brooklyn, a vastly diverse borough that includes many immigrants, and I see people every day on the subway or on the bus and I wonder about their lives. I love the idea of extraordinary moments in the lives of ordinary people. Anya in 1998 is in her thirties and is one of those people. I think there is a novelist’s longing to know what becomes of a character, and I wanted to see Anya after her singular childhood. I also wanted the novel to go beyond the collapse of the Soviet Union, and connect it to the Russian community in Brighton Beach.

JC: What are you working on next?

RM: I have been researching a house for virgins in fifteenth-century Florence. I like exploring the juxtaposition of exploding developments in art alongside the gritty and violent reality of life for adolescent girls. (Their own inhospitable landscape.)

___________________________________

Winterland by Rae Meadows is available from Henry Holt & Company, a division of Macmillan.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.