Rachel Yoder on Navigating Chronic Pain Through Storytelling

The Author of Nightbitch Considers Writing as a Somatic Practice

Deep in the summer of 2020 quarantine, the pain began. Physical and uncontrolled, this pain flared extraordinarily, red-hot and throbbing on a daily basis, in whatever place in my body it pleased, then stayed for months and months. The rheumatologist commented, This doesn’t make sense, as in I’ve never before heard the story of this pain. Another way of putting it is that she didn’t understand how my body works. The pain had something to do with other defined diagnoses, but there was no clear cause-and-effect, no clear story. But what about stress? What about grief? What about constant, unrelenting fear? As doctors have now been saying for years in answer to my many questions: We just don’t know.

Around the same time my physical misery commenced, I began working in earnest with a somatic therapist, ostensibly on the psychological pain that has plagued me for decades, but also with a hope that the work might relieve my physical agony. She also did not have answers to my questions, and in place of easy resolution offered things like: Breathe. Can you feel your belly? How can you make yourself a bit more comfortable? When my anxiety became unbearable, commensurate with my physical pain, she suggested I could drink a glass of water. When I asked her for a list of strategies to manage my anxiety, she began: Try looking out the window at something very far away.

I committed to a strict food-sensitivity diet to try and stop the pain in my body. I visited my somatic therapist each week for the pain in my soul. I was very hungry. I gazed at distant tree branches. Slowly, I began to acquaint myself with my anxiety, to explore how the cool slide of water into my chest interacted with the ever-churn of anxiety that also resided there. I charted every bite of food I ate and, then, which part of my body began to ache an hour or day later. It was tedious and, at times, disheartening, but it also was, I see now, life-changing. As a person who has paid close attention for two decades to words, sentences, and the stories I tell, it was astonishing to realize I had never given such close attention to the details, sensations, and story of my body.

Uncontrolled pain. I think this may be part of what storytelling is working to, if not make sense of, at the very least bring into language. As a reader, a story is a chance to run someone else’s consciousness through my nervous system. A story is a training manual, of sorts, for how to experience events and regulate emotions we might otherwise never encounter in our own lives. And as a writer, it’s a way of taking a somatic disturbance—anxiety, confusion, sadness—and regulating it through language and formal structure.

When a reader and writer connect through a story, we might consider this a way in which two human bodies regulate each other. One, giving words and structure to the chaos of human existence. And the other, receiving this sensory order. This makes sense, our bodies speak to each other. We are co-regulating each other, my therapist says. Do you understand? I understand. Story as meditation. Sink down into it. Story as medication. Take two and call me in the morning. Story as temporary relief. Ahh.

As a writer, it’s a way of taking a somatic disturbance—anxiety, confusion, sadness—and regulating it through language and formal structure.

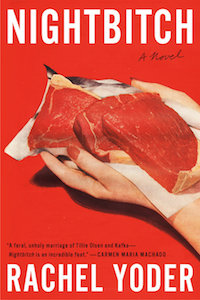

In Nightbitch, my debut novel, the main character’s physical self quite literally articulates what she is unable to say with words. Her body—via doggish transformations and unbridled, animalistic energy—expresses her monstrous, repressed anger while Nightbitch herself remains silent, unable to say anything to her husband, other moms, anyone. At first, Nightbitch fears and resists her body’s transformation; yet when she finally moves into a curious and open relationship with her changing body, she is able to transmute self-destructive fury into protective focus, clarity of vision, and creative genius.

Often in the body horror trope, the body is framed as a locus of betrayal, and its messages as grotesque, horrifying, to be feared. Nightbitch, though, challenges these conventions, positing instead: What if we listened to the body? What if the body’s messages, however horrific, are our salvation rather than our doom? What if the body is articulating the message we most need to hear?

Storytelling brings us into a regulated negotiation with pain, whether in the body or the psyche. Look, the story gently asserts. It’s okay. I have something to show you. In my own storytelling, I have objectified emotions and experiences too painful to speak to a therapist or fully admit to myself, but on the page, they become something I can manage, explore, and potentially resolve. On the page, experience becomes less scary, and the structure of story provides a comforting blueprint for how to move from one place to another. Listen, the poet Mary Oliver says. Whatever it is you try to do with your life, nothing will ever dazzle you like the dreams of your body.

Writing Nightbitch and living through this last year of pain have, ultimately, shown me how to sit with pain in my body, how to breathe into a horror I’d rather turn away from, how to live through it, because after all, is this not the human condition? I don’t mean to say our suffering is noble or beautiful. I mean that it’s unavoidable.

I still have baffling pain on a daily basis, but now it’s quieter. I pay attention to what I do to my body and how it responds. I am curious about the relationship between what I’m thinking and how my body responds to this thinking. I have not resolved the mystery of my body. I have not really figured out anything. Rather, I’ve moved from one place to another. Follow the narrative all the way through and come out the other end, my therapist says, tracing the air with her finger. Finish it. Go all the way through. Even though it may be difficult, there is a thrill in having experienced it. There is an exhilaration in having survived.

__________________________________

Nightbitch is available from Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Rachel Yoder.

Rachel Yoder

Rachel Yoder is a founding editor of draft: the journal of process, which features first and final drafts of stories, poems, and essays, along with author interviews about the creative process. She is also the creator and host of The Fail Safe, an interview podcast that explores how today’s most successful writers grapple with and learn from creative failure. Her short stories and essays have recently appeared in The Southern Review, StoryQuarterly, Catapult, and Gulf Coast and her work has also been awarded The Editors’ Prize in Fiction by The Missouri Review and with notable distinctions in Best American Short Stories and Best American Nonrequired Reading. She is currently a 2017 Iowa Arts Council Fellow and lives in Iowa City. racheljyoder.com