Rachel Kushner and Francisco Goldman on Autofiction, Identity, and the Novel

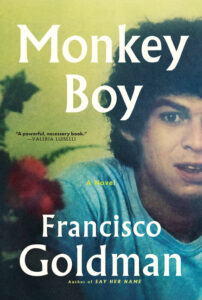

A conversation about Goldman’s new novel Monkey Boy

Early on in Francisco Goldman’s new novel, Monkey Boy, there’s a description of the narrator watching two girls whose giggles, Goldman writes, “foam over like a boiling pot of squiggly pasta.” This description reminds me of the author who wrote it, and of the sheer effusive power of this new novel, which is positively boiling over with original metaphors and insights.

I was introduced to Goldman’s work through Mary Gaitskill, who long ago urged me to read The Ordinary Seaman. Later, I became friends with Goldman. We met in Key West, in January I think of 2009, where we kept getting steered to semi-fancy literary atmospheres, parties at the homes of benefactors and so forth. Frank and I rebelled and rented bicycles and saw what felt like maybe the real Key West, its large stretches of subsidized public housing and the struggling people who work in its tourist industry. We’ve been friends ever since and I continue to read his work, not because he’s a friend, but because he’s a writer of real force and originality.

I recently talked to Goldman for a public event celebrating the release of Monkey Boy. I asked him some of the following questions over Zoom, but we were light on our feet and dealing with a faltering connection on account of a storm in Mexico City, where he lives. He had lost power in his apartment, went to a neighbor’s, lost power there, and read a few pages from the book by phone, in the darkness, with a little flashlight. Aside from being a writer of novels with rare vitality and humor, Goldman is also a brave and storied journalist who has risked his life to speak truth to power—supergonzo—so a power outage? No biggie. After our event, I sent him my questions by email so that he could answer them more fully.

*

Rachel Kushner: Your narrator is Frank/aka Frankie/aka Francisco Goldberg. It’s not you of course, but it’s also not not-you. The sly alteration of your own name, and all the biographical details that follow in the novel, remind me of this messianic idea of the world to come, when everything will be “as it is now, just a little different.” Was this minor insertion of “berg” for “man” key to the conception of the novel? By which I mean, was it enough to free you into the mythical envelope of fiction? The dirty business of fiction? You mention, at one point, “a fictionalizing finger on the scale” which is such a great phrase. But the finger is light. So light that the very work of autofiction is acknowledged in the book we are reading.

Francisco Goldman: I remember seeing Mike Meyers on television, on some late-night talk show promoting his Austin Powers movie which he’d just taken to the Cannes Film Festival where he’d never been before, and when the host asked him what he’d thought of Cannes, Myers said, I come from Canada, and let me tell you, that “ada” makes a big difference. So, yeah, that “-man” to “-berg” makes a big difference. It’s a first decisive step into fiction, into turning myself into a character that‘s going to move and act and think within a fiction. It’s a freeing myself from “myself,” from any duty to be faithful to the “known facts” as I might be if I were writing an autobiography, even if many of the components I may be giving to “Frankie Goldberg” are in fact drawn from my own life.

Another decision I made was to set it in the spring of 2007, when in “real life” Aura Estrada, my wife of two years, had only a few months left to live; a reader of Monkey Boy has no reason to catch this, but in the novel, part of which takes place on a train ride from New York to Boston, “Goldberg” remembers that a few years before he’d been on this same train but going in the opposite direction, headed back to New York on a snowy afternoon for a literary event he’s supposed to take part in at the King Juan Carlos Center at NYU—where in 2003 real life Goldman did in fact meet Aura—but Goldberg never makes it. In the Boston suburbs, a teenager commits suicide by throwing himself in front of the engine, and the train is stalled for a few hours.

The “dirty business” of fiction indeed, not letting the great love of my life, up to then, and also the most tragic and life altering event of my life into this supposedly autobiographical fiction. If Goldberg in Monkey Boy, with his light fictionalizing finger, could replace the Goldman of Say Her Name, then Goldman would never meet Aura, and so she wouldn’t have been at that beach in Oaxaca that day, and never would have met that wave that killed her.

Back during the heavy grief time, I’d been a little obsessed with the fact that I hadn’t ever really had a real love, hadn’t really known how to give and receive love in a way that could make a hopefully enduing partnership, until I was 47, the age I was when I met Aura. Even after those five very grim years, and those that followed, when I even fell in love again, with Jovi, and was gifted with the other great event of my life, our daughter, Azalea, I felt like that was a question I still needed to explore. What was it in my life—what series of events, influences, places, traumas, whatever—had inhibited me in that way, or contributed to those inhibitions, those inabilities? Sometimes people want to mystify where novels come from but often novels come from the most obvious source, simply what the writer is most persistently thinking about. Sometimes that’s a matter of looking outward, as you know.

Looking out at the Central American wars of the 1980s, and my own coming of age during that long immersion, the central subject and setting of my first novel. Thinking about José Martí, his entire adulthood lived in exile, in Mexico City, Guatemala City, 16 years in New York City, and how those are the three cities of my adulthood too, led me to write The Divine Husband. Looking out, at war, into history, in order to also look in.

Sometimes people want to mystify where novels come from but often novels come from the most obvious source, simply what the writer is most persistently thinking about.

RK: This book is about all these women, and how alive they are, but not just as presences who appear and speak for themselves. It’s also about how vivid these women are in the mind, and in the interior life, of the narrator. The descriptions are incredible. They remind me that knowing you, as a friend, I honestly think you’re a connoisseur of female strength and eccentricity. Maybe that’s why we get along so well. Can you talk about the role of women in this book?

FG: Thank you so much. Honestly, during the times when I’d most lost my way in the writing of this book, I dreamed of hearing words like that. Natalia Perez, who was Aura’s best friend, read Monkey Boy and it struck her that it was my version of that Pedro Almodóvar movie, Todo sobre mi madre (All About My Mother.) That hadn’t occurred to me, but I thought, I like that.

My own mother, Yolanda, of course, is at the heart of Monkey Boy. The visit home to Boston is mainly to visit her: if those trips home represent a searching for “myself’ in the past, they’re also a search for myself in her. Then there’s the sister character too, Lexi. In real life, I know that my actual sister, Barbara, sees us as three survivors of a brutal household, dominated by our father’s verbal and physical violence. I think most of my life was driven by this negative equation: I’m not like my father.

More recently, and certainly while writing this book, I discovered something else: I’m my mother’s son, it’s really her influence that set me on my path. She died in 2017, when I was midway into the novel, which, no doubt, intensified my focus on her, that must be behind that transport or leap into her imagined past in the book’s last section.

There’s also my Guatemalan grandmother, Abuelita, definitely a strong and eccentric woman who I adored, and the women she sent up to Boston to help my mother with housework and looking after us so that she could go to college, eventually becoming a college Spanish professor. In the novel, Frankie Goldberg visits two of those women.

As an adolescent, I had a talent for turning unrequited loves into friendships. Later my friendships with women didn’t require such painful beginnings. All my adult life, I’ve had strong male friendships too, in the U.S., in Mexico and Central America. But in the U.S., most of my closest friends are women. I guess I just enjoy their conversation and sense of humor and way of being in the world more, and I think I also relate to them more.

Look, someone who grew up with a father like mine, with a childhood and adolescence like mine, is never going to feel particularly at ease around more typical varieties of American men, especially hetero white men, that’s been my story from long before that became a somewhat fashionable thing to say. White American dudehood, in general, is just something I don’t enjoy being around. Yes, of course, you encounter many exceptions; my so called “bestie” since we first hung out in El Salvador in the 80s, the journalist Jon Lee Anderson, is obviously a tough guy, but one of the things that we shared from the start was our mutual dislike of the macho male American-Brit correspondent herd that I always stayed away from.

My closest colleague/friend in Guatemala in the 80s was the renowned photographer and human rights investigator Jean-Marie Simon: the Monkey Boy character “Penny Moore” is a somewhat hyperbolic but deeply admiring fictionalization of her. I’ve stayed friendly with most of my exes, so much so that two of them are among Azalea’s squad of six madrinas, or godmothers. After Aura died, during those first grimly frightening years, her closest female friends stayed by me like guardian angels, and now it’s like we’ve made a wider family, they love Jovi and Azalea, and they both love them.

As a teenager, in her rural pueblo in Mexico, Jovi fled an abusive adolescent relationship that was supposed to become a marriage: she came to Mexico City, and became the first women in her family to go to college. (Truly, she’s a hero to the young women back in her pueblo now.) And the strength required of motherhood, I witnessed that strength and courage every day through the last couple of years of writing Monkey Boy.

But some of those exes who’ve stayed close to me are the same women who used to tell me how emotionally “closed off,” how nearly “emotionally autistic,” I was. Why was I like that? To explore that, I brought fictionalized versions of some of those women I had loved yet failed to love into the novel too; I hope its enactment of masculinity is complex. I like the open-ended place where the novel finally landed, with little resolved, but I hope the reader senses that Frankie Gee is finally ready for love in a fruitful way.

RK: My mother also read Carlos Castaneda novels when I was a kid, and I was so confused by them. I read them also and was alarmed to think they said something about my mother’s interior life, haha. But for Frank Goldberg, the Casteneda novels are evidence of an erotic life that he wants his mother to have had.

FG: Exactly what it was. Why was there a year in high school when she was always reading and quoting from Carlos Castaneda books about a Yaqui peyote shaman? During all the years I spent on the Bishop Gerardi murder case (eventually writing The Art of Political Murder) I witnessed how good investigators and prosecutors collect disparate pieces of evidence and wait years for them to connect and cohere into the convincing narrative of a criminal case, and I was kind of playing with that: Frankie Goldberg with scattered pieces of evidence collected from his mother’s life since childhood, that finally all seem to come together in an uncannily candid conversation/confession in her nursing home.

He’s happy and moved that she had at least that, one year of love during her long loveless marriage, and sad that it was only one year.

RK: His mother’s mental fog in the nursing home seems, in a sly and logical contradiction, to be the very condition for clarity and truth. In her haze, honest words can finally be spoken. Was this deliberate? It made me think that perhaps mental acuity in a way is partly about repression. In perfect cognition, the person keeps thinks under lock and key.

FG: What an astute observation, Rachel. I’m definitely going to appropriate it into my arsenal of Monkey Boy stuff to talk about. My mother had a traditional sort of Latin American upbringing, which is to say she was taught that being a woman was all about keeping up appearances, manners, pretenses. Here’s a relevant story from when I was researching the life of José Martí. Supposedly he fell truly in love for the first time while he was in Guatemala, in 1877, with the doomed young María García Granados—his student in a writing class, no less—though he was engaged to a wealthy Cuban woman waiting for him in Mexico. But the real down and dirty on Marti’s love life was missing from his biographies, which tend to portray him as the saintly “El Apostol.”

One day in Guatemala I was talking to the novelist Mario Monteforte Toledo, who was nearly a hundred years old but extremely lucid, and he told me that his grandmother’s best friend, a married woman, had been Marti’s lover while he was in Guatemala, and that Marti, with his Cuban charm, had been a huge success with the women of Guatemala. Mario was passing down a story from his grandmother, something she never would have shared with a biographer. This was as close to a firsthand account of Martí’s life as was possible, though in Miami the Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante once regaled me, with deadpan hilarity, with a story about Martí having lost a testicle from syphilis. All those juicy details hardly ever appear in the biographies of Latin America’s “great men.” Latin Americans keep those details in their family closets, passed down from generation to generation.

All her life, my mother had kept her guard up in that way, about herself, about her own family. She had many secrets. In dementia, that barrier was lowered. She “forgot” to keep her guard up. It made her more forthcoming, honest, vulnerable, if also, at times, an unreliable narrator. It led to conversations with her son that could never have been possible before.

RK: You invoke Proust in the book but I was thinking of him already, and particularly his argument in the final volume that we only really experience our life in retrospect, after we’ve lived it. He says, “The true paradises are those paradises we have already lost.” This novel kind of seems your version of that, a way to reassemble, and look at, and even enjoy, experiences that you were merely trying to survive the first time around. The book is full of gravity and violence and pain but there’s a lot of verve and humor. How much fun did you have writing this?

FG: Total immersion. We lost our apartment in the September 17, 2017 earthquake. I’d just had a knee operation, I couldn’t flee down the six flights of stairs like Jovi did, I was trapped, leaning on my crutches, watching lightning-like fissures cracking open in the walls, the ceiling and floor wildly bucking, I was sure it was over. Afterwards, I was carried down to the park opposite where we lived. Jovi had retrieved my computer. Injured people were being carried past on stretchers. Lighting cigarettes was forbidden, so much gas had leaked out into the air. There was no WiFi. But I couldn’t help anyone. So I just sat there for hours, laptop on my lap, working on my novel.

The book was 800 pages long at one point. And yes, some of the most painful episodes of my youth are in there: the calamity of my first kiss, my father beating me in the police station, me finally beating up my father. I worked hard to recover those experiences, to make them happen on the page in as vivid a way as I could, and also to give them the lurid and absurd comedy that in hindsight they demand—one thing not allowed in my book was the solemnity or self-importance of victimhood.

Proust is explicitly invoked through his idea, expressed in one of the volumes, of a man in the second half of his life becoming the opposite of who he’d been in the first half. I embedded the dream of that fantastic possibility of transformation in the book. In some ways Monkey Boy really is about turning my past and even myself into something else. In some ways I left myself behind, and became “Frankie Goldberg.” It was only through the writing of this book that I understood—with the help of Natalia Ginzburg too—how artificial the racial and ethnic categories we’re boxed into are, and that there’s no such thing as being “half and half” anything, that we’re only fully what and who we are, in my case fully Jewish, fully Catholic, fully the son of a Ukraine-American Jew, fully the son of a Guatemalan mestiza.

It was only through the writing of this book that I understood—with the help of Natalia Ginzburg too—how artificial the racial and ethnic categories we’re boxed into are, and that there’s no such thing as being “half and half” anything, that we’re only fully what and who we are.

RK: The narrator’s mother’s family are Guatemalan, as is yours, and yet he’s also from Boston, which to me is a world of, like, donuts and beefneck Irish guys. I never considered there was a link between Boston and Guatemala until you brought up the United Fruit Company, based in Boston of course, and notoriously involved in the 1954 coup in Guatemala. United Fruit, Boston, and Guatemala. Was that something you always thought about, as a Guatemalan Bostonian, or did it only come into play while writing this book?

FG: Are donuts considered an exotic Boston thing in California?

RK: No, no, donuts in California are ubiquitous, and moreover, a very particular path toward economic stability for refugees from Cambodia (who as I understand dominate the donut industry). My point wasn’t about donuts being exotic but merely that I associate the smell of them with Boston for some reason. Forget the donut thing. What I meant is that it’s crazy that Boston and Guatemala are linked through United Fruit, even as I know this, having myself written a novel that’s in large part about the United Fruit Company. And yet, I hadn’t really thought about the implications for someone who is basically half-Bostonian and half-Guatemalan.

FG: The Latin American Society of New England is based on the old Pan American Society, located in a tony Newbury Street brownstone, and funded, in the era of Cold War “Good Neighbor” propaganda, by Boston Brahmins, including Banana Brahmins like UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, with their ties to United Fruit. My mother, like some other Latin Americans living in Boston, found a social life there, at first just by attending their lectures and parties.

But it was only so many years later, when my mother was in the nursing home, that I found out her roommate and best friend in the Catholic boarding house where she first lived in Boston, another Guatemalan woman, was a bilingual secretary at the United Fruit Company, which had its headquarters on State Street in Boston, this at the same time that it was instigating the 1954 CIA coup against the democratically-elected, leftist Arbenz government in Guatemala, while my mother was officially an employee of that government, working as a bilingual secretary in the Boston consulate. I spent years interrogating her about that, about what she or friend had noticed or knew.

But she really didn’t have much to tell me. They were twenty-something working women in Boston who were interesting in having fun, eventually finding a husband. My mother was like Stendhal’s Fabrizio del Dongo at the Battle of Waterloo, totally unaware of being present at a history-altering event. The 1954 coup plunged Guatemala into decades of military dictatorship, war and state terror, mass slaughter, the repercussions of which Guatemala is still living with to this day.

RK: In reading this novel I was wondering if younger people are aware of how intense the wars in Central America felt in the 1980s. You were there, and had personal ties. But Didion went there and wrote Salvador, and Deborah Eisenberg went and wrote Under the 82nd Airborne. You witnessed incredible violence.

FG: From 1979 to about 1991, I was there more than I was in New York. And even when I was up there, I really was mostly down there. Then I took a long break and started again with Gerardi case in 1998. Those years were my true education and coming of age in too many ways to recount here. I went there out of college, literally to become a writer, to find my place in the world as a writer. I supported myself, barely, as a freelance magazine journalist and eventually began writing a first novel in which the U.S. and Guatemala could somehow be fused into one literary-geographic place. I am marked forever by what I experienced in Central America in those years—the horror and evil and suffering I was close to, but also the incredible courage and dignity and generosity I witnessed too.

If you’ve read Bolaño, you know how the wars and political violence of the 1970s and 80s marked our Latin American generation, and that as writers it radically separates us from the so-called “Boom” generation writers that came before. I never stop thinking about and asking myself what I still owe to that experience. I’ll write about it again.

The protagonists of that historical catastrophe are Central American; they’re the ones who lived and overwhelmingly gave their lives, who survived and endured. even if gringos were responsible for so much of that nightmare. You’ll notice, if you read Bolaño, or Castellanos Moya, that they never commit the gaucherie, if I can call it that, of explicitly blaming the U.S. for the violent political catastrophes depicted in some of their novels, even though of course they know what happened. They’re “our” stories. But an American like Deborah Eisenberg is writing for an American audience, she’s performing a brilliantly subtle and deeply felt sort of assault on conscience and obliviousness. An essentially binational writer like me is pulled in both directions.

_________________________________

Monkey Boy by Francisco Goldman is available now from Grove Atlantic.

Rachel Kushner

Rachel Kushner is the author of the novels Creation Lake, The Mars Room, The Flamethrowers, andTelex from Cuba, a book of short stories, The Strange Case of Rachel K,, and The Hard Crowd: Essays 2000-2020. She has won the Prix Médicis and been a finalist for the Booker Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Folio Prize, the James Tait Black Prize, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, and was twice a finalist for the National Book Award in Fiction. She is a Guggenheim Foundation Fellow and the recipient of the Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her books have been translated into twenty-seven languages. Her fiction has been published in the New Yorker and the Paris Review, and her nonfiction in Harpers and the New York Times Magazine.