Rachel Beanland on Managing Time in Fiction

On the Careful Balance Between Scene and Summary

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

My son, Gabriel, turned 18 a few days ago, and while I’d like to say that I am generally good with birthdays—even milestone birthdays—I was not particularly good with this one. I spent hours looking through old pictures, trying to figure out how it was possible that this child of mine could be both the wide-eyed baby staring up at me from an exersaucer and the young man sitting across from me at our dining room table.

I’m a novelist who spends a lot of my time thinking about time. The success of my books is dependent, in part, on how deftly I can manage this most precious of commodities. In fiction, time is flexible, and if I manipulate it carefully, my story’s pacing is neither too fast nor too slow. So, how is it that I don’t have a better handle on where the last 18 years have gone?

Most stories, in the Western literary tradition at least, are linear, which means the narrative moves forward in time. How much time passes is up to the writer. Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” takes place over the course of—no surprise here—an hour, Ian McEwan’s Saturday a single day. We set our stories over weeks, months and years. Elizabeth Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things traces the life of Alma Whittaker from the moment she is born to the moment she dies, nearly a century later. Yaa Gyasi isn’t satisfied with even one lifetime—her first novel, Homegoing, unfurls across eight generations.

To help readers keep track of how fast time is moving, writers are taught to use time markers, which might be phrases like “later that day” or “the following month” or might be more subtle references to light or temperature or atmosphere. Describe the frost on the grass and we know it is a winter morning, the sound of the cicadas and it must be a summer night. These breadcrumbs are helpful, but what really keeps us hurtling through time is the writer’s careful balance of scene and summary.

Scenes are comprised of a character’s actions, dialogue, and thoughts, and they are rife with internal and external conflict. A character wants something, but there is a roadblock, and by the end of the scene they have usually had to be make some kind of interesting choice or transformation. They have undergone some kind of change.

Literary theorist Gérard Genette defined a scene as a “temporal duration” in which story time equals narrative time—or how long it takes us to read a story. If I wrote the story of my son’s childhood in straight scene, it would take you 18 years to read it.

Summary becomes our friend when we need to dramatically speed up time. Maybe we want to fast-forward through the boring bits or brush some unpleasantness under the rug. The colic that kept us up at night or the soccer season Gabriel spent on the sidelines can be dealt with in as little as a few words.

We write the scenes that are most resonant, then rely on summary to pitch us forward in time, until we arrive at another important moment.We writers rely on a combination of scene and summary because our novels and stories should—ideally—be longer than a sentence and shorter than a 26-volume encyclopedia. We write the scenes that are most resonant, then rely on summary to pitch us forward in time, until we arrive at another important moment. The time Gabriel was goofing around at a piano and I sat by, amazed, as he picked out and played an entire song by ear—that’s a scene I’d write a thousand times.

Beyond scene and summary, we have other writerly tools to employ if what we want to do is play with time. We can pause the story, which means we stop all action, using the void in time to provide backstory or other information that would be difficult, if not impossible, to convey in straight scene or summary. I might press pause to explain that we adopted Gabriel from Guatemala.

Another way we navigate time, in fiction, is to slow the story down. Joan Silber calls this kind of writing “slowed scene,” Monika Fludernik calls it “time-extending narration,” Seymour Chatman calls it “the stretch.” Whatever we call it, the idea is that if we examine a short piece of action very, very closely—using lots of detail—narrative time can actually exceed story time. The slower the action, the more important it must be to the story. “Length is weight in fiction,” writes Silber.

The key to deploying slowed scene successfully is choosing the right scenes to slow down. If we describe a routine visit to the pediatrician in vivid detail, our readers will grow frustrated and maybe even confused. What was so important about the pediatrician’s office? Why spend all our time there? What we must slow down instead are moments of great joy or trauma—moments that, in some way, change the outcome of our story.

The slower the action, the more important it must be to the story.There are lots of moments from Gabriel’s childhood that I want in slowed scene. The day we met him, in the lobby of the Marriott Hotel in Guatemala City, of course. But also, the evening I accidentally slammed his tiny hand in my car door and ran with him the two blocks to the emergency room. The night we introduced him to his little sister. The afternoon he said good-bye to my dying dad.

The author Janet Burroway writes, “When people experience moments of great intensity, their senses become more alert and they register, literally, more than usual. In extreme crisis people have the odd sensation that time is slowing down, and they see, hear, smell, and remember ordinary sensations with extraordinary clarity.”

She’s right. I remember everything about that first day we met Gabriel. The way his tiny face peeked out at us from a nest of thick blankets. How little he weighed in my arms. Our instinct, when we finally had him to ourselves, to strip him of his footed-pajamas and examine his delicate toes.

But what about all of the everyday stuff that came next? The diaper changes and baths and bedtime stories? The swim practices and teacher conferences and band performances? I don’t remember half of it, and I hate myself for that because it’s in all those moments that his childhood unfolded.

In fiction, we sometimes write scenes of “indeterminate duration,” which were made famous in the 19th century by writers such as Henry James. Characters sit at a window or maybe they wander across a grassy knoll. Are they occupied for a few minutes, an hour, the duration of an afternoon? It’s hard to tell because the physical action in which they engage is repetitive or continuous.

With scenes of indeterminate duration, we become interested not in the character’s movements, which are mundane, but in their mental processes, which may be anything but. We throw time markers out the window because they distract from our desire to know the character’s interiority, and when change occurs—and it always does—it comes from within.

There is something about these scenes that appeals to me. Maybe it’s because my life these last 18 years has been a series of repetitive motions, maybe it’s because I am in my head all the time. Or maybe it’s because, when we write these scenes, we grant ourselves permission to ignore the passage of time completely and to focus instead on what it all means.

_________________________

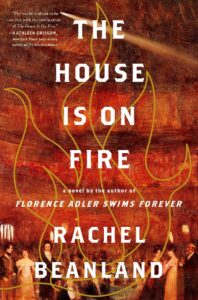

Rachel Beanland’s The House Is on Fire is out now from Simon & Schuster.