On August 21st, as he was delivering a presentation on the origins of the Batman comics to fifth-graders in Georgia, Marc Tyler Nobleman received a curious note from the school’s principal. It was his second presentation in the Forsyth County school district, which had invited him to talk to students about Bill Finger, the little-remembered co-creator of DC’s signature character, who Nobleman had written a book about.

As Nobleman started the second presentation, he saw that the principal’s note was a kind of bowdlerizing warning. “[O]nly share the appropriate parts of the story,” it read, instructing him not to use the word “gay” when describing Fred. Nobleman felt bewildered, and his bafflement only grew when he learnt that the principal had emailed the students’ parents to apologize for what their kids had heard in the presentation. Shortly after, other district principals contacted Nobleman, also advising him not to say “gay.” Feeling “trapped,” as he told the New York Times, he agreed not to use the term in subsequent presentations, then did so, anyway, deciding it was absurd to excise something directly relevant to the story of why it had taken so long to get credit for Bill. The schools canceled his remaining presentations; one principal, Jennifer Caracciolo, went so far as to compare Nobleman’s reference to a gay son to Nazi death camps. “It would be almost like if someone was doing a speech to kindergartners and they talked about the Holocaust and the horrors of the Holocaust,” she humorlessly told the Times.

As I read about Nobleman’s escalating incidents, I remembered an unfortunate evening two years ago, when my wife and I were having dinner with a family member and her new boyfriend. They had invited us to his apartment in Manhattan, where he had prepared a lavish spread of food. For a while, the boyfriend seemed gently reserved, talking primarily in interjected puns and dad jokes, his smile contemplative and wry. As we sat down to eat, the light conversation turned, somehow, to the subject of book bans aimed at “protecting” kids, and the boyfriend suddenly erupted. It wasn’t appropriate for kids to see LGBTQ material until they were “old enough,” he said, voice rising. The shift felt surreal.

My wife noted that openly queer teachers in certain schools across the country were no longer able to casually have photos of their partners on their desks, should kids happen to ask about them, and that this sort of erasure raised awkward questions for how LGBTQ parent couples were supposed to navigate things; when we eventually had a kid, would we not be allowed to show up together to parent-teacher conferences? Would our kid be allowed to participate in a family tree project if it didn’t conform to the “mom and dad” model? He didn’t have answers, but continued to insist that kids shouldn’t know about queerness until “the right time,” whenever that might be.

I didn’t want to shut him down. Tough as it was, I wanted to listen. I have little interest in binary, Manichean thinking where x is absolutely right and y absolutely wrong; life is far more byzantine than any binary can convey. But it felt hard that night to talk dispassionately about this. My voice and temper rose, too, until I decided to try to cool things down. We agreed to let it go for the moment, and the boyfriend and I even hugged each other after; he thanked us for being able to discuss about something “difficult.” We smiled and said our goodbyes when it got late. But as my wife and I walked back to the subway, I still felt tense. We never actually broached the subject with the boyfriend again.

I wondered, as I reflected on Nobleman’s story and this unexpectedly polemical dinner, what world our own child might eventually find. These incidents have become commonplace in the polarized, kneejerk-reactive American landscape, where simply acknowledging that queerness exists is enough to get a book or speaker pulled from a classroom, or to transmogrify banter into battle. Nobleman’s case is remarkably literal—saying the word “gay” was all it took for him to be labeled “inappropriate”—but the simplistic nature of his peccadillo, to me, perfectly captures the unthinking puerility of this moment in time.

Queerness, you see, is still an emblem of something Other, a threatening, non-normal deviation from the supposed defaults of society. That one principal compared Nobleman’s mention of a gay son to talking about the Holocaust with kindergartners is so out-of-proportion as to be funny, but it reflects the fact that too many people imagine queerness as an inherently adult-level concept that minors must be shielded from. Schoolchildren will be assigned countless books and films featuring heterosexual, cisgender couples holding hands, proclaiming love, or kissing; were the same books gender-flipped, they would suddenly be “too advanced,” too tough to talk about, too racy and risqué. None of this makes sense, except in light of the persistent conservative belief that queerness is equivalent to hardcore porn at best and child molestation and Satan-worship at worst.

This line of thinking also presupposes that queer kids, or queer parents raising children, do not really exist, a delusion reinforceable only by these attempts to evade the topic altogether in schools—an avoidance that will feel especially jarring, say, to the child my wife and I want to have. That kid will already know that families with two mothers exist, only to be told in school that they dare not acknowledge it, or that their family is somehow less legitimate. I don’t like being treated, as an adult, like She-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named, but I can take it; I had just hoped to offer my little one a world a little less dense with shame.

*

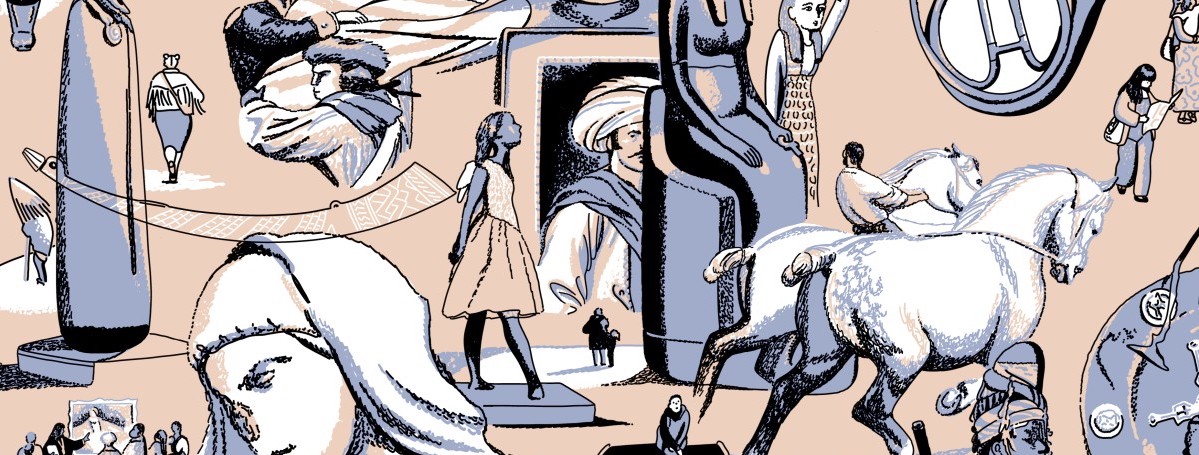

I found myself thinking about all this as I reread Roaming, a charming, deceptively simple graphic novel by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki. The Tamaki cousins rose to fame for the children’s comic Skim (2008) and especially for This One Summer (2014), a beautifully understated queer coming-of-age story that won a Caldecott Honor and holds the prestigious distinction of being one of the most banned books in America for, amongst other things, its frank discussions of sexuality. Being in that maelstrom of controversy had come as a surprise to the Tamakis, and, with Roaming, as they told the New York Times, they had set out to craft a story featuring college-age girls. “We knew that we wanted to have the freedom to depict what we wanted to depict, talk about what we wanted to talk about, in ways that weren’t necessarily Y.A.,” Jillian reflected.

Roaming certainly feels free. It beautifully lives up to its name, roaming gently through the lives of its three female protagonists during a brief trip to New York City over a few days, capturing the way that a small span of time can contain a lifetime, and the way the moments that change us are rarely the ones we expected. To be sure, the story features a number of scenes of queer flirtation and, eventually, a hazy, dreamlike scene of Sapphic sex rendered with beautiful atmospherics. But for all this, the queerness in Roaming is subtle—and that, to me, is powerful in of itself in this era.

So often, the books whose bans make the news have more obvious subject matter, like Jazz Jennings’ children’s book about growing up trans, or countless other texts about affirming one’s identity. The overtness of these books is significant in of itself; we shouldn’t need to be coy about such things in a society that truly believes that human experience is vast and variegated, uncategorizable on any simple binary. But there’s something to be said for the books—banned and otherwise—that depict queerness more quietly, not because they’re trying to suppress themselves or surreptitiously smuggle some message in, but because queer identity in these narratives is simply a foundational part of their worlds to begin with, as natural and normal as anything else.

These quieter stories can feel cathartic. When I’m flustered by yet another article about a drag-queen story hour event being attacked by conservatives as “grooming,” or about cute, seemingly unimpeachable books about queer joy being cut from curricula, I feel an impulse to be loud and proud, to shine my queerness in everyone’s faces like a floodlight. But in other moments, I want to just be, my queerness simply another soft identifier, a flash of bluepink on the leaf of me on a branch bursting with other tinted leaves.

The queerness in Roaming is subtle—and that, to me, is powerful in of itself in this era.But subtlety can still subvert, especially if its subtlety suggests normalization of an idea. If anything, this aspect of Roaming might ironically make it more subversive in this determinedly non-nuanced American atmosphere. The comic doesn’t need to argue for the legitimacy of its queerness; it’s just there, fundamental as atoms.

And I loved that. It felt so disarmingly pleasant to exist in the cool-toned understatement of these girls’ world. It made me think of my own charged college years, when I hadn’t yet found the courage to come out; to have stumbled across a book like this would have seemed a little marvel, a small Damascene revelation. But I think, too, of the world I want my own eventually kid to find, where they, too, can go through that most human muddle of figuring out who you are, without needing to worry about whether or not their queerness will muddle that muddle too much.

*

The book begins with an ecstatic reunion in an airport many readers will recognize: two best friends who haven’t seen each other in too long. Dani and Zoe grew up together in Toronto but now go to different colleges. To reunite in style, Dani has suggested that they spend a few days vacationing together in Manhattan. Dani’s first appearance is one of manic glee, rushing through Newark Airport the moment she sees Zoe to topple onto her in a hug, and Zoe, recognizably more reserved, happily receives the greeting.

But it isn’t just the two of them there; a third girl, Fiona, a classmate of Dani’s who Zoe has never met, is present, too. When Fiona says “hey” to Zoe, Fiona—eyes made up, hair a glamorous cascade, chic coat lined with fur—is shown with a seductive smile, cheeks aglow, implying her attraction to the more butch Zoe from the get-go. While Dani and Zoe are new to the city, Fiona, who grew up in Winnipeg, quickly establishes herself as a veritable New York veteran. “Dani. Honey. No maps. We don’t want to look like tourists!” she tells her tripmate after they get to Manhattan with the softly chiding air of the experienced. “It’s all about attitude. Confidence,” she says, the panel showing a smug smile. When Dani asks if Fiona knows how to get to their hostel, she calmly responds, “Sure. Easy. Manhattan’s a grid. It’s virtually impossible to get lost.” They find their way to their hostel, and their grand trip begins.

In a way, these early pages set the tone for the story’s arc and central conflicts. Dani is a stereotypical tourist, wanting to see all the things with an endearing, nerdy naivete; Fiona is the know-it-all, the projector of power, the quiet but confident girl with capital-O Opinions about how to do things. Zoe is somewhere in-between, generally happy to go along with either what Dani or Fiona want to do. And because Fiona is so “confident”—or, at least, wants people to believe she is—she takes what she wants, from a shoplifted pair of sunglasses to alcohol with a fake ID to two joints from the hostel owner to Zoe herself. A day after meeting the new girl, Fiona is already tenderly touching Zoe’s cropped hair, taking Zoe’s hand, and praising the “cool dyke thing” she has going on. Zoe, as ever, goes along with it, but she genuinely seems to enjoy Fiona’s attentions.

Dani, more innocent and nervous about doing “wrong” things, doesn’t join in when Fiona drinks in their hostel with Zoe or when the two go outside to smoke the first of their joints. As Fiona’s actions get bolder, the grandiosity of her statements also swells; she declares that the art that Dani likes is privileged Western propaganda and that because humans deserve to go extinct for what they’ve done to their planet, Dani shouldn’t enjoy the Natural History Museum. Dani’s anger slowly builds at such dismissive quips, as well as at her sense that Fiona is taking Zoe from her. Things finally break down after Fiona and Zoe come back from smoking and fuck in the dark in a glorious, dreamlike sequence; the next day, Dani leaves by herself before the two wake up. Zoe becomes an anxious wreck when she realizes her friend has vanished without leaving a note, and as she tags along with Fiona, she also becomes flustered about the cost of turning “roaming” on in her phone—the more literal meaning of the comic’s title—because she needs to save money. Eventually, Zoe goes to find Dani by herself, irking Fiona, and this leads to each character beginning to learn anew who they are and what they want.

For the most part, all of this is relayed realistically, both the book’s scenes of wandering through iconic New York locations and domestic moments between the girls at their hostel rendered with a quiet verisimilitude. Anyone who has visited the city with starry eyes will likely recognize Dani’s own wonder at the colossal blue whale in the Natural History Museum, the glorious immensity of cheap pizza slices, the sheer abundance of things in a flagship store, or the overwhelmingly cool-seeming recommendations of the person who purports to know the city’s hidden gems. And it is easy, too, to recognize the tension in imagining that someone is coming between you and your best friend, or in realizing that you do not know someone as well as you think you do, and the person you once thought the epitome of enviable, experienced cool isn’t actually who you want to become.

In a few brief but breathtaking moments, though, the art and storytelling alike morph into something dreamier, and these are my favorite scenes, capturing the magic-seeming reality of the girls’ lives just as well, if not better, than the realism. When Fiona and Zoe make out in the butterfly vivarium of the Museum of Natural History, the art depicts them floating and tumbling between lepidopterans, gravity and panels abandoned for a daydreamy spread. Later, when they slip outside at night to smoke the first of her joints, the art becomes appropriately trippy, Fiona’s giant head filling the page, her braid unfurling like a great snake, capturing the mythic, baroque atmosphere the world can attain on cannabis. And, after Fiona leaves Zoe the next day, irritated by her inability to let go of Dani, there is a great two-page spread of her as a giant pair of legs walking across the city, her monstrous proportions reflecting her outsized presence in everyone’s lives, as well as the monstrosity of her attitude: that she is always right, always an opinionated pseudointellectual know-it-all, and always vampirically in need of another hit of others’ energy, which has swollen her ego and comic-page body to the size we see. It is a quick image you can gloss or pore over, subtle and in-your-face all at once, like much of Roaming.

But it’s the second cannabis scene that stands out most, when Zoe, flustered that Fiona still isn’t back, decides to go onto the fire escape to smoke Fiona’s second joint. Dani, ingenuous as ever, warns that it’s “trafficking” if Zoe’s caught. In one moment, Dani is peering at Zoe on the fire escape; then, sudden as a fox in the night, they are altered. In the panels that follow, they become their younger selves, clothes and hair and backdrop shifted, even as they’re still discussing the present day. They have been quietly transported, without leaving their hostel, to a party from years ago when Zoe’s hair was still long and femme, and Dani was wearing the kind of attention-grabbing outfit more associated with Fiona in the present day.

Dani asks about the dangers of drinking as Zoe prepares to light the joint. “Weed’s different,” Zoe says. And there’s certainly something special about being high: the clock of the world seems slower, the old relationships of things less stable. Cannabis, as this scene captures well, can be a grand enchanter, and there is indeed a kind of transfigural witchery when the girls inhale that pilfered spliff—with Dani getting over her prim fears and demanding to take the first hit. They then wander about a parklike landscape, Dani worrying about what happens if they get stuck in a loop of bad thoughts and Zoe wanting to mosey away. Then, in a blink, they’re back on the floor of their hostel room.

The first time I saw these panels, I was surprised by the temporal shifts. But I also recognized, as a somewhat new lover of entheogens, the softly psychedelic—in its literal meaning of mind– or soul-manifesting—transformation in this narrative sequence. Their brief smoke takes them back, helping them to see the present anew by reexamining their pasts—Dani’s tendency to catastrophize and try to control situations, Zoe’s quest to find her identity both in gender presentation and in school—and though they don’t come to any explicit new conclusions, it’s clear that something has gently changed. In a way, the joint is a spiritual healer, a “healthy cigarette” as Etgar Keret puts it in his touching short story of the same name about a traumatized soldier and a mother with dementia who smokes joints—codenamed “healthy cigarettes”—to help their respective pains melt away, for a bit. It made me think, too, of Louisa May Alcott’s memorable description of hashish in her curious short story, “Perilous Play”: “A heavenly dreaminess comes over one, in which they move as if on air. Everything is calm and lovely to them: no pain, no care, no fear of anything, and while it lasts one feels like an angel half asleep.” How apt this sentiment feels, too, for this dream-lit moment between the girls.

Though the girls have somewhat changed, much is left unsaid unsaid—and that feels intentional. The story is done, without being done, because it’s still being told.Just as their dream lifts, Fiona returns. She’s a drunken mess and has puked in a cab, and she’s called Dani to pay for the ride because, despite her glamorous self-assuredness, she doesn’t have the money. That she requests Dani is meaningful; she’s dismissed her for much of the trip, yet Fiona clearly knows that Dani may be kind-hearted enough to help. When Dani and Zoe go down, Fiona becomes furious that Zoe is seeing her like this, too, and when she’s back in the room, she screams into her pillow. The titan has fallen, as so many colossal monsters of myth do.

The story ends soon after, with the girls checking out of their hostel, Fiona silent and distant. Dani suggests they go to Coney Island for one last adventure and, because she’s grown, she invites her erstwhile enemy. Fiona initially rebuffs her invitation, but Dani talks her into it, and the improbable trio heads to Brooklyn.

The last panel shows the back of the subway train chugging along; the girls, along with the landscape, have evanesced away. The story ends without really ending, the metro car rushing without reaching its destination. But we know it’s going in the direction the girls wish in more ways than one: towards Coney Island from Manhattan, judging by the Avenue I station they breeze past, and, more profoundly, towards new self-understandings.

Though the girls have somewhat changed, much is left unsaid unsaid—and that feels intentional. The story is done, without being done, because it’s still being told. The not-fully-knowing is the thing, an inconclusive conclusion that feels truer to how we are never done growing, truer to the capital-M Mystery of life, truer to the subtle-but-big ways we may metamorphose over the course of a few days.

I can’t help but cherish Roaming. Its slice-of-life normalcy, queerness made quotidian, makes the story feel at once nostalgic and universal, softspoken and a subtle fuck-you to the book-banners, a world charted with the realization that there’s much more map to explore. Roaming may be aimed at readers in college or older, but it isn’t because of its Sapphic scenes; it’s because such stories are best appreciated when you’ve lived a bit longer, felt a bit more.

It made me excited to share stories with the little one I’ve not yet met, where they will meet families unlike theirs, and, just as crucially, ones they recognize immediately with a smile, so, by the time they are ready for something like Roaming, they’ll be able to follow the story of the girls without its quiet queerness seeming extraordinary at all.