Qian Julie Wang on Zou Or, The Act of Leaving

"I worried that the act of returning home—only it was no longer that, not really—had left me irrevocably unraveled."

Zou [Or, The Messy Middle]

走 [zŏu, Mandarin Chinese] verb:

(1) to walk;

(2) to leave, to go away;

(3) to die, to pass away.

The first time I returned to China at age 12, after living as an impoverished undocumented child in New York City, I could not stop crying. My parents and I returned only for a month, and I somehow found opportunity to cry everywhere: when my grandfather gave me a red envelope for each Lunar New Year I’d missed, our lost years in currency form; in the family kitchen, eating homemade dumplings, reunited once more with a full stomach and fuller heart; in our ancestral courtyard, staring at the red calligraphy strips on the brick walls, confronting the ashes of a childhood that might have been. I was a walking wound, and I worried that the act of returning home—only it was no longer that, not really—had left me irrevocably unraveled.

But when I boarded the plane to go back to North America, our new home, whatever that meant, I felt my innards bottle up again as the little airplane on our flight map moved further and further west. By the time we landed, the calm stoicism that had kept me safe in America restored itself on my face and in my body. Far from the messy emotions of family, I could once again exert control over my feelings, pack them up and store them neatly in the basement of my heart.

It sank in then just how much that act of zou so early in life had been in itself a form of death I had never mourned.

I assumed that basement would stay locked, only to discover on my second visit at age 18 that China might always be a master key. As I walked out of the airport doors, through the muggy pollution and onboard the minivan bus, I felt my rib cage loosening, my heart unbuckling. And as three-odd hours of scenery passed, the skyscrapers of Beijing melting into the farms, dirt, and cornrows of outer Hebei province, before shapeshifting into the hazy industrial skyline of my city of birth, Shijiazhuang, I could not keep from sobbing, inking myself into the memories of my fellow passengers as that strange girl in mourning.

This would repeat again for my third trip to China, this time at age 22, and I am ashamed to admit that the discomfort of being inundated with so many emotions all at once kept me from visiting more often. I figured I must have had some recessive mental illness that emerged only when I returned to my birth country. Best to keep it locked up, I figured—throw away the key and never return to that fertile ground where all emotions came pummeling for me.

It did not all start to make sense until I returned a fourth time at age 27, upon news that my paternal grandfather was dying. I received just forty hours’ notice to make the trek around the world. I had been in the middle of another 15-hour day at my white-shoe law firm when I received the call from my father, telling me to secure an emergency visa, to buy plane tickets, bus tickets, and train tickets—everything I needed for the twenty-plus hour trip back to my ancestral home in Handan.

On the fifth and final leg of that trip—a cab ride from the train station to Handan Central Hospital—I finally managed to collect myself, dry my tears, and powder the blotches on my face. But when I arrived at the foot of my grandfather’s bed, my father already seated on a metal stool at his side, I saw not my beloved Ye Ye: not the person toward whom I’d taken my very first steps when I learned to walk; not the one with whom I’d shared an easy, unspoken kinship; not he who once rode his bike around town at age 94; not the sage who, even after becoming partially paralyzed from a bus accident, continued to follow President Obama via international news. Instead, I saw a small, wooden puppet, skin and flesh melted against bone. His shoulders were a fraction of their former size, and it didn’t make sense to my eyes or my brain how my spirited, mischievous, gentle Ye Ye had morphed into the sunken skull before me.

His eyes gleamed at the sight of me, finding light that they had not found, according to my father and aunts, for many weeks. “Qian Qian!” My name came out in two gasps, as if he were choking. And then, just as quickly, the light departed again. I knew to do nothing but keep busy, wiping at the skull with a damp cloth, bringing water to the wizened lips, summoning the nurse for a floor fan. The body responded, sure, but I knew then that my Ye Ye was gone. And when I could bear no more, I excused myself, telling my father I needed a nap. On our walk to the hotel together, I kept my eyes dry, my heart stony. But the minute I closed that door behind him, my willpower dissolved into my heart. I fell to bed in a crying heap. How could this be? Where had the years gone?

It was then that I realized that after my very first act of zou, my first steps toward Ye Ye, I had engaged in yet another.

Weeks later, on the day I was to leave for the train and the bus and the plane, Ye Ye’s body was still around. As I grabbed my bags and gave him a peck on the forehead, he started to rouse. Sensing this, I moved faster, unable to bear the finality of this goodbye. Even so, something pulled at me when I came upon the threshold. I could not help myself from pausing, from turning. And then I saw why. For there was Ye Ye, back again, eyes filled with light and tears, returning just to see me off.

The vision propelled me out of the door. Amidst the running and the sobs, I could not find my breath. I slowed only when my name came from behind me. I pivoted to find my fourth aunt, the youngest and the one closest to my father, chasing after me. We were a mirror of each other, tears streaming down our faces, throats choking on our hearts.

“Qian Qian,” she yelled, still running toward me. “Promise you’ll come back. I’m afraid that after Ye Ye passes—we might never see you again.”

I nodded and, in the most futile attempt to comfort her, swallowed my sobs.

“Zou, zou ba,” Go, go now. “Don’t miss your train.”

The echo of her words was the soundtrack for my journey back. On the plane, when I was somewhere north of Russia, I realized for the first time that in Mandarin we use the word “zou,” to leave or go, to describe the act of walking, the act of leaving to go far away, and the act of passing away. It was then that I realized that after my very first act of zou, my first steps toward Ye Ye, I had engaged in yet another: I had left to live in the opposite side of the world. And it sank in then just how much that act of zou so early in life had been in itself a form of death I had never mourned. Ye Ye and I had had a beginning—my learning to walk, our first shared smiles—and an end. But we had had no chance to create all the memories that form the messy, priceless middle: no New Years together, no fights, no trips to the zoo, though we had shared all the love in the world to build it.

From those restored elements emerged a bravery of sorts: to dare to face the discomfort of living as a vulnerable, feeling human being once again.

Weeks later, my father called me at work again. “Ye Ye zou le,” he said. By then I was already ensconced back in my American life, executing legal strategy with all the calm precision of my logical, unemotional self. I missed Ye Ye’s funeral that week, just like I had missed Nai Nai’s, who had died so abruptly in the years between my first and second visits that my father had not even had time to make it back.

But on the day of Ye Ye’s funeral, for the first time on U.S. soil, something came unglued in me. That morning, I stared at my reflection in my bathroom mirror over 7,000 miles away from where my beloved grandfather was being cremated. I started crying and could not stop. His last glance replayed as I drowned in guilt. Why had I not stayed with him through his final moments? Why had I not bothered to visit more when I had the chance?

That was 2014. I have not returned to China since. I have not kept my promise to my aunt, and I live in daily shame over that fact. But despite the distance, something has shifted within me. In the years since, my heart has started waking up, my emotions thawing. I am no longer soldiering from task to task, the automaton America prefers its Asians to be. I have lived so long in survival mode: in the need to hide, lest I be deported; the need to work, lest I go hungry; the need to numb, lest I collapse. It is as if, when Ye Ye embarked on his act of zou, the world returned to me that childhood safety I had once known so many years ago. Ye Ye’s zou somehow restored in me all the elements of myself that my own act of zou had beaten out. And from those restored elements emerged a bravery of sorts: to dare to face the discomfort of living as a vulnerable, feeling human being once again.

I have been trying to return to China since February 2020, to uphold the promise I made my aunt. The global pandemic has made that exceedingly difficult, and in the time since, my maternal grandfather has been diagnosed with dementia, losing, memory by memory, his sense of reality. It is likely that by the time it is safe for me to visit him in his quarantined nursing home, he will have no idea who I am. I find myself steeling again at the prospect of yet another end.

My biggest fear is that with my parents will die the last of my ties to my familial roots. And in response to that fear, to preempt the feelings that might emerge, I am tempted give up and let those ties fade now. But then I remember that my version of zou is not yet final. With so many—aunts; uncles; cousins; babies, now toddlers, soon preschoolers—there is time still to build that messy middle and reclaim some of what immigration has robbed from us. To allow space for Lunar New Year celebrations and fights and laughter, to make room for intimacy to build and heartbreak to unfold.

To recognize that the messy and the uncomfortable and the vulnerable sit at the very heart of what it means to live. As his final gift, Ye Ye opened my eyes to that truth. And every time I love without restraint, cry from the very depths of my soul, and laugh from the bottom of my belly, I see Ye Ye before me, guiding me as he did during my very first steps. And in those moments, I think that perhaps, his act of zou is not quite so final either.

_____________________________________

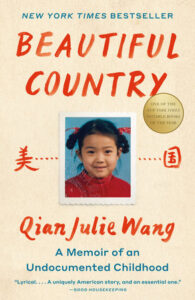

Beautiful Country: A Memoir of an Undocumented Childhood by Qian Julie Wang is now available in paperback from Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Qian Julie Wang

Qian Julie Wang is a graduate of Yale Law School and Swarthmore College. Formerly a commercial litigator, she is now managing partner of Gottlieb & Wang LLP, a firm dedicated to advocating for education and civil rights. Her writing has appeared in major publications such as the New York Times and the Washington Post. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and their two rescue dogs, Salty and Peppers.