Pulitzer Prize-Winner Ilyon Woo on Craft Lessons From the Late Filmmaker Dai Sil Kim Gibson

On Han and Jung and How to Tell a Story

I’ve never heard an Asian woman—certainly not one in her eighties—cuss as exuberantly or continually as the late filmmaker Dai Sil Kim Gibson. I picture her throwing her head back, glass raised, cackling at the sound of her own F-bombs, her wild hair shaking: kinetic iron spirals. She cooked like she lived and filmed, with feeling. She made the best bindaetok, or Korean mung bean pancakes, rushed, hot, and crusted. (Her secret ingredient: kimchi juice.)

She was also famous for her Iowa Fried Chicken, based on a dish made by her beloved husband’s mother, only even better, by all reports. (Here, too, a tang of acid—lemon—made it fly.) From this riotous cook, activist, author, and keeper of history—Dai Sil, as she preferred to be called by all—I learned two vital storytelling lessons that are also living lessons, which changed my writing and me.

These lessons begin with the Korean word han, which has been called an existentially Korean phenomenon of grief or anguish, one that defies translation—though lately, there has been some contestation over the term and what it means. In her book Silence Broken, about Korean women who were systematically sexually enslaved by the Japanese during the second World War, Dai Sil defines han as: “long sorrow and suffering turned inward.” “Long” is not confined to a single lifetime. It accrues in layers, grows in knots, individually but also potentially over generations and passed down.

Dai Sil defines han as: “long sorrow and suffering turned inward.” “Long” is not confined to a single lifetime. It accrues in layers, grows in knots, individually but also potentially over generations and passed down.Han saturates her work—whether Sa-I-Gu, her film about the Los Angeles riots; or A Forgotten People, about Koreans left behind on the Sakhalin Islands; or the film version of Silence Broken. In each of these documentaries, han haunts. And yet, Dai Sil’s power as a storyteller derives from her ability to see the individuals whose sufferings she tells, beyond their collective trauma.

My first, vital lesson from Dai Sil on this theme came to me as a story. I assisted her—and her dear friend and frequent filmic collaborator, Charles Burnett—on location in Korea on the film version of Silence Broken. But I was not present for their early interviews of the “Halmeonis,” or grandmothers, as Dai Sil preferred to call the former “comfort women”—a terrible euphemism she purposefully deployed. (I honor her word choice here, wishing only that I knew the individual names of the women, as she had. Names are so often the first things to go when stories are passed down, especially in translation.)

Dai Sil told me of how, when she initially approached the “Halmeonis,” many of them had already been interviewed before—repeatedly—and would launch into what had become a recitation of trauma. Dai Sil found this unsettling and remembered asking one particular Halmeoni if she might tell something of what she knew and loved and did in her life before the camps.

“You want to know about my childhood?” The Halmeoni was at first incredulous. No one had expressed such interest in who she was before the events that came to define her, at least in the public eye. But Dai Sil recognized the fullness of who this woman was, and in doing so, received and represented the fullness of her story.

The Halmeonis, despite many of them having repeatedly spoken to the press—could be particular about who they told their stories to, who they wanted to be in the room. When a young male production assistant entered the space, one Halmeoni, Dai Sil recalled, pointed to him and commanded: “Out.” She was sure that he was of Japanese ancestry and was livid at his presence, even when Dai Sil promised her he was of Korean ancestry. Another Halmeoni questioned why Charles Burnett was directing the project. What did this American filmmaker know about their story? That he was Black did not enter into the equation: What they cared about was that he was American, not Korean. This is when Dai Sil said, gently: “His people have known han, Halmeoni.” And with this quiet utterance, a word became a bridge, by which these ladies admitted an unknown traveler into their world.

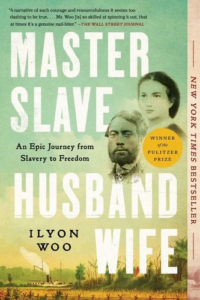

I’ve returned to these stories time and again as I’ve worked on my own telling of the story of two individuals whose experiences and history lie far outside my own—Ellen and William Craft—in my latest book, Master Slave Husband Wife. Dai Sil’s oral history interviews have reminded me of the importance of trying to see who the Crafts were before and after the unforgettable escape from slavery that has come to define them—the fullness of who they are. And her phrase—“His people have known han”—gave me a framework for beholding the fullness of their experience, what came before them, what they carried, and what they passed on. (Incidentally, it would be Charles Burnett who would introduce me to a descendant of the Crafts, a great-great-granddaughter, Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely.)

Then, too, there was another operative Korean word, also considered a translation challenge: jung. Approximations include love or affection or sympathy or attachment, but it, like han, is seasoned in layers, and it is complex. You can hate someone and feel jung for them. You can feel jung despite yourself. Jung, too, inhabits and haunts.

Both of these concepts, han and jung, guided my understanding of the Crafts and their story: on the one hand, the saturated suffering, unbound by time or lifetime, on the other, the jung that brought the Crafts together not only with each other but with their people and their world, making it possible and necessary for them to carry on. This is why my original title for the book read: Master Slave Husband Wife: An American Love Story. Only in my head, it was American Jung story.

Purists may say that these expressions are uniquely Korean. Or, that as a Korean American writing in English, I’m not getting them right, that they are in translation.Purists may say that these expressions are uniquely Korean. Or, that as a Korean American writing in English, I’m not getting them right, that they are in translation. Just a flavor, a style, a flair, like my cooking isn’t “really” Korean, like Dai Sil’s chicken isn’t “really” Iowa. I’m pretty sure I know what Dai Sil Ajuma—from whom I learned about one word, han, while feeling, deeply, the other, jung—would say to that, and it’s not printable. But I can freely conjure the gesture, as Daisil, with her husband Don chuckling beside her, hoots and raises her glass.

______________________

Ilyon Woo’s Master Slave Husband Wife is available now.