Princeton Goes to Prison: Teaching Paradise Lost to Incarcerated Students in New Jersey

Orlando Reade on Privilege, Freedom and the Importance of Reading Disobediently

The youth correctional facility lies in the green outskirts of a town on the Delaware river, where the state line between Pennsylvania and New Jersey reaches its westernmost extent. To get there, you drive up a tree-lined avenue with fields on both sides. In winter, the slanted sun makes the frost glow and sometimes a pheasant runs beside the car. Underneath the trees’ dark canopy, a building appears ahead. An arrangement of curving planes and dark glass windows, it looks like a regional bank headquarters, neither welcoming nor forbidding. It was built in the late 1960s, when President Lyndon B. Johnson reformed America’s prison system and expanded it, laying the foundations of mass incarceration.

I was there as a PhD student teaching in a prison education program run out of Princeton and part of a state-wide scheme. Our students were working towards an associate’s degree, which was accredited by a local community college, and some of them would go on to get a BA from the state university. The program’s existence raised difficult questions about education and inequality. To teach at an Ivy League university and a prison at the same time was to receive a view of two poles of American society: one group lavished with attention, praise, and opportunities, the other harassed, humiliated, and punished. But there were similarities as well as differences: the conversations we had with our students in prison were no less vital and stimulating than those at the university. Often more so.

Prisons can be very literary environments. In an age of technological distraction, they are places where reading is still a form of entertainment. The life situations of incarcerated people seem to inspire them to read ambitiously. A student once told me that it was common see people walking around the prison with copies of Being and Nothingness. Some of our students were self-identifying scholars, poets, and writers of short stories. But others didn’t care about literature. Often it was the only course they were able to take: another handful of credits on the long road to their degree. Not being able to assume their interest, we, as teachers, had to try to make what we taught valuable to them. How could literature speak to their lives and ambitions, without being patronizing or depressing? How could it represent the world as it is, with all its suffering and violence, while showing it to be a place in which we should want to live? I came to see Paradise Lost as a powerful answer to these questions.

I wanted to put into practice what I had learnt at the youth correctional facility. To use literature to make sense of our world.

The correctional facility was a thirty-minute drive from the Princeton campus, and every week the graduate students had to scrabble to find someone with a driving license and a car they could borrow, so it was always a relief to sink into the drive along the grey highways of the Garden State. It was a facility especially for young men: if they turn thirty inside, they are shipped out to another facility. To enter the prison, the visitor gave up their ID and received a name tag in return. I was so nervous the first time I arrived that I shook the hand of the officer when he reached out to take my ID. When all the teachers had arrived, we went through a double gate. An officer arrived to escort us down the curved corridors, which made it impossible to see all the way to the end. We passed slop buckets containing the remains of dinner: a smell provoking a deep and unforgettable disgust. Then we waited outside the classroom block, while the officer unlocked the gate.

Inside the classroom block, the corridor was lined with pictures of US presidents and civil rights leaders, and a neon poster that said:

KEEP ALL NEGATIVE

THOUGHTS TO-

SELF

The classes took place in the early evening, when others were exercising in the yard. There were long waiting lists for classes, so our students had to have special determination or luck to be there. They seemed to pride themselves on being different. But still they complained about humiliating strip-searches and arbitrary invasions of their cells. The classroom felt like a refuge from that. There was generally a calm, friendly atmosphere. Lining up in the corridor before class, they would chat with friends from other cell blocks. After the first few weeks, I felt relaxed too.

The students were bored of Hamlet by the third week of studying it. They understood the plot and they didn’t want to talk about it anymore. As an undergraduate in the UK, I had studied the canon of English literature: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Spenser, Milton, Wordsworth, Woolf, and so on. I had learnt what these texts said about the fundamental experiences of life, about love and loss, often before I had had those experiences myself. By my mid-twenties, pretty much all I knew how to do was to read English literature and write about it. But teaching in prison, I couldn’t take its value for granted.

One afternoon, when the class was meant to be planning their final papers, one of them was distracted. This student—I will call him Omar—was normally one of the sharpest in the class. But that day he was talking to his neighbors, who weren’t listening to him, or talking to himself. I sat at the desk next to him. He said he wanted to become a ‘sovereign citizen.’ He explained what this was: the idea that you could become a citizen of your own nation.

I was skeptical about the practicality of achieving legal separation from other people: “Isn’t it only when your actions harm someone else that you break the law?”

“I’m sick of this place,” he said simply.

“Think about Hamlet,” I said, remembering my purpose. “He lives under a government that is cruel, arbitrary, that he hasn’t consented to, in a country where he is denied the rights he was guaranteed at birth. Hamlet develops a language to describe this condition, a way of speaking that the agents of the state will not understand. It’s insane or sounds like it is, but it infects his listeners. Maybe you could write your paper about this.”

He was quiet for a moment. Then he said: “Why weren’t we talking about this all along?”

*

Slipping along the highway on our drive back from the facility, I would feel exhaustion mixed with relief. There was a natural camaraderie among the instructors: we would chat about what had happened in class, things our students had said, any exercises that had worked especially well. It was worlds apart from the unhappy competitiveness of the university.

After the first semester, I was hooked. I signed up to teach again, and ended up teaching a class almost every semester for the next five years until I left America. I don’t say this to boast. The role of education programs in the prison system is complicated, to say the least. In their teaching evaluation, one student wrote: “Orlando teaches us to speak right, not to speak street.” I was horrified: their degree required them to write in formal English, but I certainly didn’t see it as the correct way of speaking. I sometimes felt that my students would have been better served by a teacher who shared more of their experiences. There were times of frustration and despair—with the system and occasionally with the students. But it was also an experience that permitted moments of real intellectual intimacy. I can’t say what the students got from my classes, but I have often thought about what I learnt from them.

I continued teaching in prison as I lost my way. Crises are common among PhD students: the work is solitary, difficult, and seemingly endless. Those who struggle to find their place often retreat into themselves, growing their hair and beards long, losing the ability to present their thoughts coherently, stuttering and blanching while talking, failing to write or producing knotty, ill-tempered, unreadable tracts, becoming fearful of others and unable to take in new knowledge. The malcontents of graduate school are proud, envious, impotent, and bitter. I had it worse than most. I developed a kind of reader’s block, picking up too many books and finishing none. I lost confidence in my work. Teaching in prison seemed like the only thing worth doing. Sometimes, while waiting for the students to arrive in class, I looked out of the narrow windows across the grass, to the basketball court where men in their beige khaki exercised in the golden light, and I remembered that this unhappy period of my life would eventually end. My students were one reason to feel sad at that thought.

The morning after the 2016 election, there was a light but persistent rain. I went to the Princeton campus, where everyone seemed to be in shock. That evening, in prison, our escort was unusually cheerful, whistling as he walked us to the classrooms. This was a reminder of the political divide between the liberal America associated with the university campus and the America of the prison. The prison officers’ union had been the first to come out in support of Trump. In class, the students were subdued. They seemed to know what the election results meant for them. The funding for their education would be taken away. Sentencing would get tougher. The invisible punishments they faced on being released would multiply.

In the years after that, the classroom felt more political, and our discussions would sometimes zero in on difficult aspects of our students’ realities. This wasn’t my doing: the students were themselves often thinking about white supremacy and racism. I didn’t discourage it. At the same time, it taught me to appreciate literature that created a space to draw connections. A freedom to make meaning for yourself.

After four years at the youth correctional facility, I was assigned a class at a state prison. This was my first time teaching at an adult facility. Some of the students would be inside for life. It was also the first class I ever got to design and teach on my own. I called it “World Poetry:” I wanted to think about poetry in the context of the whole of human history, to take the students from the early writing systems of Mesopotamia all the way to the present. We would discuss Egyptian tomb inscriptions, the Hebrew Bible, Renaissance poetry, and blues music. It was overambitious, but I wanted to put into practice what I had learnt at the youth correctional facility. To use literature to make sense of our world.

*

To get to the prison, I took the train to Newark, where, from the faded glamour of the station waiting hall, I ordered a taxi to take me out of the city center—not far from the mosque where Malcolm X’s murder is said to have been planned—and on to the highway roaring past the international airport. Finally, we would arrive at a security checkpoint. Sometimes the driver didn’t want to go through the gates, and I walked the final half mile along the grassy verge to the visitors’ entrance. Inside, I put my phone in a locker, went through airport-style security, and waited for an officer to escort me through the concrete precincts. By then, the yard was empty, but if it was a fine evening, outside the kitchen a few men would be leaning against the wall, relishing the dusk. As we entered the education block, a square of officers waited to frisk the students on their way to class. I greeted the officer on the gate, and he pointed me towards a classroom.

Paradise Lost guides us from despair and resentment, through the fantasy of boundless pleasure, into an encounter with the real world.

On the day of my first class, I was late. I called ahead to tell the prison, so they wouldn’t send the students away. When I finally got to the classroom, twenty unfamiliar students were waiting. Flustered, I unpacked my materials, and when a voice offered to help, I refused. As I introduced myself, another interrupted, asking how long I had been teaching for. I said four years, not unconfident of my experience. I was twenty-nine, and no longer felt young, but I was conscious that some of them were older than my parents. I handed out copies of one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. When we were discussing the poem, I mentioned its meter. Several students asked follow-up questions about this unfamiliar system of rhythm, and I agreed to talk more about it in the next class. That’s why I decided to bring in the opening of Paradise Lost.

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe…

I wrote the first two lines on the blackboard and explained how its meter, known as iambic pentameter, alternates between unstressed and stressed syllables, with five stresses (or beats) in each line. I wrote a mark above each one:

/ / / / /

Of man’s first dis-o-be-dience, and the fruit

I asked the class to read it aloud with me, and together we emphasized the stressed syllables like a tuneless choir. I had no idea what they might make of this rather abstract exercise, but as soon as I had finished explaining it, a student—I will call him Mark—put his hand up. The first line is disobedient, he said simply. I asked him to explain. To follow the meter, Mark continued, the reader must choose whether to confine “dis-o-be-dience” to four syllables or else say “dis-o-be-di-ence” and in doing so disobey the meter.

It was a brilliant insight. Freedom is not only a theme of Paradise Lost, Milton tells us, it is embedded in the very experience of reading it. In a “Note on the Verse,” which acts as a brief introduction to Paradise Lost, he explains why he decided to write in unrhymed iambic pentameter. He says rhyme is a kind of “bondage,” a trivial sing-song effect that restricts what the poet can say. Besides, Milton says, many of the best poems—the epics of Homer and Virgil—didn’t rhyme. Because of this, his decision to write unrhyming iambic pentameter, also known as “blank verse,” was restoring an “ancient liberty” to poetry. The fact that Mark had seen this, in the smallest fragment of Paradise Lost, made me think about Milton’s poem in a new way.

After that, the other students kept returning to Mark’s comment about reading disobediently. They wanted to learn more about meter, but they didn’t want to accept it. In one class, we were talking about another line of verse. I was trying to show them where the stresses went, and one student suggested that I was trying to teach them to speak like me. I was taken aback by this. I racked my brain to find a way to show them that meter wasn’t a matter of personal opinion or accent. Finally, I found my example. The next class, I gave them the lyrics to “Amazing Grace.”

We all know how Aretha Franklin sings it, I said, but unless we know that the lyrics follow a particular meter, we can’t understand how this song was written.

Amazing grace how sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me

I once was lost, but now am found

Was blind, but now I see…

However you sing it, each verse has lines of iambic meter, alternating between unstressed and stressed syllables, in lines that alternate between four and three stresses. This is called ballad stanza, and it’s the basic structure of the verse. I think this helped to convince them that meter was not subjective, but they continued to think about it in relation to freedom and oppression.

As the semester went on, I poured more and more time into the class, hoping to arrive at some new understanding by the end. When that came, I was exhausted and uncertain what conclusion we had reached. But the students had taught me to see something that I only realized in retrospect. As we looked at the literature of the past, they were respectful but not reverential. They weren’t reading in an abstract, academic way, they were reading in the context of their whole lives, as something that might help to explain why we had ended up where we were, and this was why they couldn’t relinquish the idea that poetry had something to do with the inequalities of the modern world. To see that is to want to read disobediently.

Reading disobediently might, paradoxically, be the best way to honor Paradise Lost. As a young man writing pamphlets in support of marriage reform, Milton had disobeyed the words of Jesus which forbade divorce. He maintained he was obeying a higher principle: the principle of charity, or love for others. This was no pacifist principle: it would later cause Milton to advocate for the abolition of unjust institutions—state religion, censorship, monarchy—by force if necessary. But his ideas about freedom are not timeless. For him, freedom was above all a question about whether to obey or disobey a Christian God. There is another version of freedom, which people have claimed for themselves in moments of radical change: the capacity to define the meaning of freedom for oneself. This is also something invited by the poetic darkness of Paradise Lost. The poem plunges us into an uncertain world where we meet a kaleidoscopic, seductive Satan, and then a wooden, authoritarian God. We have to weigh their respective arguments for ourselves. In doing so, Milton’s poem extends a peculiar kind of freedom to its readers, to make our own choices and our own mistakes. It is an experience of political self-determination and an education. But the lessons we take from it may not be the ones Milton intended. Over the past three and a half centuries, readers have honored this poetic darkness and radicalized it, reading it on their own terms. As with Virginia Woolf’s devouring of the canon, Hannah Arendt’s unfaithful fidelity, and Malcolm X’s late political transformations, reading disobediently is a way of relating to the past, not as a burden but as a new beginning.

*

In the final book of Paradise Lost, the archangel Michael comes down to Eden to prepare Adam and Eve to enter the fallen world. He tells Adam the whole of world history, from Moses to Christ to the Protestant Reformation to Milton’s present, and then to the final dissolution of the world, the defeat of the antichrist by the Messiah, new Heaven and new Earth, endless bliss, and that’s it.

After hearing this, Adam tells Michael he has learnt that “to obey is best” (XII:561). This is a disarmingly humble lesson. But obedience is a process, and Michael tells Adam that it will lead to knowledge, faith, virtue, patience, temperance, and love. Together, these possessions will be “A paradise within thee, happier far” (XII:587). Adam is now equipped with the tools to make his way in the world. It is time to go.

The angel tells him to wake Eve. Adam goes to the bower, where he finds her already awake. God has appeared to her in a dream, so she already knows what Adam knows. Eve has the final spoken words in the poem:

In me is no delay; with thee to go,

Is to stay here; without thee here to stay,

Is to go hence unwilling (XII:615–17)

These lines, beautifully balanced, display a happy equanimity. Since Adam’s company is a kind of Paradise, Eve is happy to go into the fallen world with him; to stay in Paradise without him would be to lose it. This expresses a more general thought—that loving relationships are the best of what we have in this world. The fact that marriage in Middlemarch is not an ending but a beginning is the reason Virginia Woolf said that George Eliot’s was one of the few English books for grown-ups. Something similar is true of Paradise Lost: it wants to leave the reader with the knowledge necessary to think for themselves.

Angels have come down to escort Adam and Eve out of Paradise. Milton compares this to the mist that “gathers ground fast at the labourer’s heel / Homeward returning” (XII:631–2). Adam and Eve are returning home too. One angel leads them down to the plain that lies beneath the garden.

They looking back, all the eastern side beheld

Of Paradise, so late their happy seat (XII:641–2)

Behind them, the gate of Paradise has closed and God is beginning to turn its green into desert. The final lines are perfectly balanced, and dignified, with their own quiet momentum:

Some natural tears they dropped, but wiped them soon;

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and providence their guide:

They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way (XI:645–9)

This beautiful passage comes as a reward for the substantial work of reading Paradise Lost. It draws together images that have occurred throughout the poem—Eve dropping a tear after her dream of Satan, Adam seizing her by the hand, their separation and reconciliation—gathering them all into an image of union. They are alone but together, leaving Paradise but still in Eden, sad but resolute. Epic poems often conclude with homecomings, but this is a strange one, since Adam and Eve have never been in the fallen world before. For the reader, too, it is a homecoming. We are leaving Milton’s Eden and returning to our own world. If the poem has done its work, it should look different.

As I had been traveling between the university and the prison, I had been traveling between an American version of Eden and an American Hell.

Beginning in Hell and ending in the world, Paradise Lost guides us from despair and resentment, through the fantasy of boundless pleasure, into an encounter with the real world. In doing so, it reminds us that it is only in the world and not in any fantasy that we can be happy. Since the world is shared, and people are different, it follows that democracy is the best system of government, because the decisions are made through the deliberation of different views rather than the tyranny of a single decision-maker. This is the political argument buried in the end of Milton’s epic, one that for centuries readers have seen and made sense of in their own ungovernable ways. It should be clear by now that the afterlife of Paradise Lost was exactly what Milton hoped for and, at the same time, more extraordinary than he could have imagined.

*

When spring came, I took my Princeton class outside, and we discussed Paradise Lost in the shade of a tree. Then I walked through the green cloisters of the university to get on a train to Newark to teach in the jaundiced light of the prison classroom. It wasn’t until the final week of the semester that I realized why Paradise Lost had taken hold of me. As I had been traveling between the university and the prison, I had been traveling between an American version of Eden and an American Hell.

The town of Princeton was founded in 1683, less than ten years after the publication of the final version of Paradise Lost. The university was founded sixty years later by men who had likely read Milton’s epic and shared many of his religious beliefs. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Puritans built America’s universities on the model of Eden: green cloisters protecting the innocent beings inside from the world outside. It was common for speakers at graduation events, as they looked out at the happy students ready to enter the world, to quote the end of Paradise Lost. During that period, men from the Protestant ruling class laid the foundations of America’s prison system, as an expression of their ideas about Hell, where the guilty could be used as slaves. But if the modern world is still haunted by this cruel will to punish, the best part of Milton’s legacy is the belief that unjust institutions should be abolished and tyranny of all forms will fall.

One of the students—I will call him Roger—was a tall, bald man with thick glasses, probably around seventy years old. He worked as a classroom assistant, so I would often see him before the other students arrived, clearing up the classroom, and we would always exchange a few warm words. It was almost certainly Roger who had offered to help me on the first day as I was scrabbling to begin my class. He used language in a way that I found difficult to understand—I don’t know how to describe it—but he was unfailingly enthusiastic. One day, in class, he started talking about Newark in the 1960s, the riots of 1967, the Black Panthers, slave religion, and African languages.

In his final paper, Roger wrote what I quickly recognized as a critique of my class. Drawing on Mark’s insight into Paradise Lost, and the idea that poetry could be bound by laws, he argued that poetry should instead be dedicated to freedom. The essay ended with an unattributed quotation:

Nothing vast enters the life

Of mortals without a curse

I was struck by these words. They summed up what the students had been trying to tell me about literature and its relationship to the world. They also feel true of Milton’s vast poem: not as an apology for its shortcomings, but as a description of the world in which it has had a long and complex afterlife.

While I appreciated Roger’s paper, I was unable to give it a good grade. There were some serious issues with the grammar, and it didn’t build a coherent argument of the kind I was meant to be judging. But it was a generous and perceptive piece of writing. I gave it the highest grade I thought my colleagues would allow, and I praised it in my comments. Still, I felt conflicted: the situation was itself symptomatic of the problem Roger had diagnosed. In the final class, I gave the papers back, and said my goodbyes. As I was leaving, I saw him. He was carrying a mop and bucket towards the empty classroom. I apologized for having to give him a low grade.

“It’s all right, Professor!”

I asked him where the quotation at the end of his paper had come from.

“Sophocles!” he said.

He had found the quotation in a book that a professor had given him in Trenton State Prison in the 1970s. He had kept the book ever since, he said, and will have it the day he gets out. The book said that the invention of writing had been the beginning of man’s destruction. He turned to walk away, and over his shoulder let out a sudden laugh that echoed for a moment in the empty hall.

*

Once class had finished, I would walk out into the hallway where the other guards were milling around, having just frisked the students, and one of them walked me out, back through the yard, now dark. I reclaimed my belongings from the locker and called a taxi. When I was leaving, the captain on the gate would say: “Be safe.”

Once I was in the car, and we were out of the front gate, sliding onto the dark freeway, the driver was often curious to know what I had been doing in prison. I would tell them, and I was always interested to see what they said, whether they would scoff at prison education or sympathize. After my second-to-last class, shortly before I flew out of the international airport next to the prison, my driver was a young Muslim man from the Bronx. When I told him what I had been doing, he said that his younger brother had been killed in a drunk driving accident when he was a teenager. He regretted that the driver responsible, who was 19 at the time, had received a 16-year sentence. He and his family had forgiven the man, as their religion had taught them.

When we arrived at the train station, I was could hardly speak to say goodbye. I was moved to think that, in a country where so many people are treated as disposable, some are committed to forgiveness—refusing to dispose of someone else, precisely when it is most difficult.

__________________________________

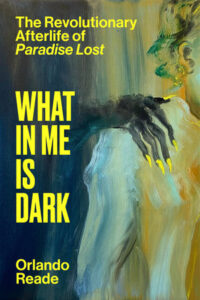

Excerpted from What in Me Is Dark: The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost by Orlando Reade. Copyright © 2024. Available from Astra House.

Orlando Reade

Orlando Reade studied at Cambridge and Princeton, where he received his PhD in English literature in 2020. For a period of five years, he taught in New Jersey prisons. He is now an assistant professor of English at Northeastern University London. His writing has appeared in publications including The Guardian, Frieze, and The White Review, where he also served as a contributing editor.