Prince Was One of the Loneliest Souls I've Ever Met

Neal Karlen on His Complicated Relationship with an American Icon

I pray to God Prince was dead by the time he hit the floor.

I pray Prince wasn’t cognizant, even for a mite of a moment, that he was dying alone in a nondescript elevator, in a Wonder Bread suburb of the racially-fractured city that was one day too late in telling him his hometown—blacks, whites, the whole Crayola box of colors and ethnicities—loved Prince as much as he loved Minneapolis.

Because there’s one thing I’m positive I know about Prince. After knowing him in forever-alternating cycles of greater, lesser, and sometimes not-at-all friendship over the final 31 years of his life, until our final peculiar phone conversation three weeks before he died: His greatest—and perhaps only—fear was dying alone.

Prince didn’t care if the end came in a Chanhassen, Minnesota, elevator inside a building where he owned all the buttons, or in an opulent prime minister’s suite in a Paris hotel, inevitably—and idiotically—redecorated for his arrival by a clueless management apparently determined to re-create for his pleasure Liberace’s living room.

He just didn’t want to die alone. Yet he always accepted what was coming, and was trying to prepare, he told me as far back as 1985.

Of course the questions must be asked whenever someone says anything about what Prince actually said, or thought, or did: “How do you know? Why would he tell you? Did you see that?”

_______________________

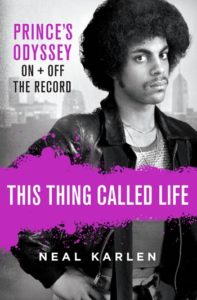

From This Thing Called Life: Prince’s Odyssey, On and Off the Record by Neal Karlen.

_______________________

Well, personally, on this and several other topics, in a wide array of settings, yes, I witnessed this and saw that. Once upon a time, in what feels like a previous lifetime, I wrote a gaggle of articles and interviews for Rolling Stone and then the New York Times with Prince and about Prince—his thoughts, worlds, bands, and best friends of the moment, what he wore on his head and the height of the heels on his feet.

I still am not sure why he chose me to occupy one compartment in his life—the most compartmentalized life I’ve ever seen, trapped inside the loneliest soul I’ve ever met. Few of his real friends knew who each other were, or even if they themselves were “real” friends. He didn’t like many people, and I still have no real idea why he abided me.

And then, in the 1990s, I quit.

I didn’t quit Prince, I just quit writing about him or hanging around his world. I still don’t know if I was brave or an idiot to walk away from the only real scoop rock and roll had to offer in those days.

I was still young enough to believe it was worth trying to be a “real” writer, writing real things, or at least running away to join other circuses besides entertainment journalism, where life was the proverbial high school with money—and the entire world reduced to the simple binary equation of “that’s cool” or “that’s not cool.”

If I didn’t quit, I knew way back, I would never be taken seriously as anything more than Prince’s bobo, a slur in the baseball world denoting a professional sycophant to a superstar player. In rock and roll, I figured, the equivalent bobo might be, say, the only reporter someone like Prince would give interviews to, or hang around with, or divulge the inner meaning of his heels. (“I don’t wear ’em cuz I’m short,” the five-foot-two musician told me in 1985. “I wear ’em cuz the women like ’em.”)

Two of the eight times I published what I thought were “real” books, I received anonymous purple flowers.

These are the first words I’ve written about Prince since back in the day. Until now I’ve kept a promise to myself that I wouldn’t write about him anymore. In the years after the interviews, he asked me to write a couple of things with him, and I assented. The projects sounded so ridiculous I figured no one would believe they existed anyway.

In the 1990s, I wrote the libretto to a rock opera called The Dawn, retitled for direct-to-video release in 1994 as 3 Chains o’ Gold. Prince had released the experimental set of narratively interconnected videos on the marketplace as a present to Mayte, the first of his two ex-wives. For a story, he gave me a couple of details of what he wanted: a setting in the desert, and a princess being courted Valentino-style by an inscrutable, magical—ahem—prince.

He also gave me the indescribable experience of catching a true genius in the act of being a genius.

“Will you pay me?” I asked.

If he did, I knew, I’d be set free if I ever wanted to sell out. I knew I could never write another article about him again, at least not in the guise of an objective journalist. I would have to include so many caveats, full disclosures, and conflicts of interest as to render any scribbling about Prince worthless.

“No, I won’t pay you,” Prince said. “But you can say you wrote a rock opera with me.”

Good point, little purple guy, I thought. And damn, looking back half a lifetime ago, that was the most profitable thing I’ve ever worked on, karmically speaking.

I also wrote a manifesto, composed as if I were writing a real third-person magazine profile, explaining why Prince was on the verge of changing his name to that goofy glyph—a fact then known only to him, his manager, and me. He told me the manifesto was for a time capsule to be buried on the grounds of Paisley Park with, among other things, his will. I have no idea if it ever was, though there is proof that such a time capsule exists.

I put my copy of the manifesto on a last-century floppy disk in a Minneapolis storage locker where I kept memories I didn’t know where to put.

*

I always told Prince I knew he didn’t honestly consider me a friend, but as one of the few people in Minneapolis who was probably awake, the way he always was, in the middle of the night, and was “Willing and Able,” as my favorite song of his is titled, to talk about loneliness and death.

I even rubbed it in, in the opening of my third and last Rolling Stone story featuring Prince on the cover, published in 1990.

The phone rings at 4:48 in the morning.

“‘Hi, it’s Prince,’ says the wide-awake voice calling from a room several yards down the hallway of this London hotel. ‘Did I wake you up?’”

No, you jerk, you never woke me. Well, actually you did a few times, but I was always happy to hear from you, even when you were so lonely and depressed you could barely speak. I told him I wanted to be a real writer, not the bobo formerly known as Neal. I wanted to be Nathanael West, and though he had no idea who Nathanael West was, he seemed to understand completely.

And we stayed in touch.

Sometimes we talked on the phone several times a year in the middle of the night for between several minutes and several hours. Sometimes I got letters, sometimes on purple stationery. Two of the eight times I published what I thought were “real” books, I received anonymous purple flowers.

Over 31 years I’d guess we saw each other in preparation for published profiles on a couple of dozen occasions, saw each other socially 30 or 35 times, and talked on the phone a few hundred times in the middle of the night. About 50 unanswered (or unheard) calls from an “unknown” number registered on my phone during the hours when only Prince would call.

When he wrote, I’d always write him back care of Paisley Park. I have no idea if he ever got most of my letters, because I never had any idea what the hell was going on over there, even when I used to visit.

An hour before I quit on that story, I sent my editor a scan of an old letter he sent me that began, “Neal, Please treasure our friendship as I do”—yes, he drew an eye for an I—and ended “4 real. I love you.”

I don’t know why I sent the editor that letter; perhaps I wanted her to know I really knew him, we really were friends. Or maybe I just wanted to read it again and smarten up.

Still, like the rest of Minneapolis, I neglected to tell Prince I loved him back until it was too late.

He once told me he believed in heaven, and he thought if he made it there it would look exactly like earth. You can look it up: Rolling Stone, September 12th, 1985.

If he was right . . . well . . . hey, Prince! Will you give me a call one last time? I forgot to tell you something.

I love you, too.

And so, that’s what I wanted to actually tell Prince a week after he died, and for a little while beyond.

Leaving critical matters forever unmentioned, is, alas, a favorite track on the B-side of the civic album known as Minnesota Nice. On that reverse face of the local pleasant-at-all-costs ethos also lies a brutal passive-aggressiveness and meanness kept undercover.

I pined for the presence of the actual Prince. He often said he liked Minneapolis’s brutally frostbitten winters, because it “keeps the bad people out.”

And soon enough after he was gone, I was glad Prince wouldn’t be calling ever again, even to hear my regretful un-saids. Dead, he was instantaneously embalmed in his own myths, deified and commodified. I was grateful there would be no Resurrection for a proper goodbye. If Prince reappeared again, I was sure, he would die a second time the moment he saw what was being done in his name, memory, and supposed honor.

Then, George Floyd was murdered. And I wished Prince could arise again, just to do battle with that Minnesota Nice flipside.

At its worst, that alternate face camouflages “racism with a smile,” as one woman who immigrated to Minneapolis in 1998 from Somalia portrayed the duality of the local situation to the New York Times in June 2020.

It had only been days since a white Minneapolis cop put a knee to the throat of George Floyd, an African American, for almost nine minutes. The spot on the pavement is less than a mile away from where Prince went to high school, two miles from where I live.

And once again, after years being grateful he couldn’t see what was going on, I pined for the presence of the actual Prince.

He often said he liked Minneapolis’s brutally frostbitten winters, because it “keeps the bad people out.” I wondered what he’d have to say, write, sing, and play now that Minneapolis had been exposed to the world as a place where the deadliest enemy had grown within.

Alive, Prince had become ever more politicized with the years. Near his end, in 2015, he’d released the song “Baltimore,” centered on Freddie Gray, 25 and black, who less than a month before had died while in the custody of Charm City’s police, sparking more than a week of protests and rioting.

“Nobody got in nobody’s way/So I guess you could say it was a good day/At least a little,” Prince sang, “it was better than the day in Baltimore.” True that, at least in Minneapolis, where Prince recorded his infectious gospel-like melody with a chorus of protest chants.

The day after the single hit Soundcloud, Prince played for almost three hours for a Baltimore “Rally 4 Peace.” While performing “Purple Rain,” Prince interrupted his own song to talk to the audience.

“The system is broken,” he said. “Next time I come through Baltimore, I wanna stay in a hotel owned by one of you. I wanna leave the airport in a car service created and owned by one of you.”

He didn’t get specific about which “you” he meant in the crowd encompassing his usual spectrum of ages and colors. He didn’t need to. Black, white, young, old, “woke,” asleep—you.

Five years later, I stood at the spot where George Floyd had died days before. I wondered what if Prince had lived, what would the now almost 62-year-old have told his own hometown, a dot on the map in Flyoverland, now at the center of the world?

I had no idea. But I knew it would be great, that you could prob- ably dance to it—and it would probably be released in time for George Floyd’s funeral.

I still miss the mamma jamma.

__________________________________

From This Thing Called Life: Prince’s Odyssey, On and Off the Record by Neal Karlen. Copyright © 2020 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Neal Karlen

Neal Karlen is a former contributing editor for Rolling Stone, Newsweek staff writer, and regular contributor to The New York Times. He is the author of Babes in Toyland: The Making and Selling of a Rock and Roll Band, and other books ranging in content from minor league baseball to fundamentalist religion to linguistics. A graduate of Brown University, he lives in his hometown of Minneapolis.