Pramila Jayapal on Changing the Establishment from the Inside

The US Representative on the Status Quo, Democracy, and Organizing

I never thought I would run for office. For 20 years, I had been an activist pushing for change from the outside. I had used every tool I could think of in my toolbox to advocate for positive changes on issues from immigration to environmental justice to economic inequality. I had led voter registration drives, rallies, marches, even nonviolent civil disobedience actions where I was arrested twice. I deeply believed that organizing, advocacy, and storytelling by real people were what made change happen.

Truth be told, I was quite cynical about elected officials. Over the course of my two decades of organizing, I saw too few who were willing to use their positions to exercise leadership, particularly when an issue was seen as “controversial.” The things I had seen—government incursions into civil liberties post-9/11, Islamophobia, and anti-immigrant sentiment, among others—regularly required people who were willing to speak out before an issue was popular. And yet, too many elected officials were inclined to wait before speaking out; they followed rather than led. Even in my state, where we did have some champions and some successes, it took enormous amounts of pushing and in some cases years to get the attention of elected officials.

I was also deeply frustrated at the lack of diversity and representation I saw among those who held elected office. Low-income people, people of color, immigrants, women, and other marginalized communities were simply not represented. I had to explain for too long, too hard, and too loudly about what seemed like obvious problems to me. Many in government had been there for a long time and did not seem to understand what life was actually like for the huge number of their constituents who had very different backgrounds and experiences from them.

Even in the Democratic Party, few elected officials were willing to talk about race or class, or take on stereotypes that were baked into the policies that even Democrats proposed. Perhaps this struggle around race and monied interests should not have been surprising to me or any other student of history: just look at slavery and the Dixiecrats; President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Crime,” which increased the incarceration of black and brown people; and President Bill Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it,” which led to cutting aid to poor people, as well as his draconian 1996 immigration bill, which criminalized immigrants and expanded detention and deportation without due process.

As an activist, I had even taken on President Barack Obama for being the “Deporter-in-Chief,” a still unpopular but in my view necessary critique of an otherwise extremely popular president. I had taken mental note of a long list of times when Democrats said talking about race was “divisive,” or that we shouldn’t focus on institutionalized racism because it would push away white voters, or that certain policies to rectify the wrongs we saw would be counter to our interests in some false analysis of national security or safety.

When I first began organizing after September 11 around the detention and deportation of Muslims and Arabs, there were very few elected officials willing to stand with me. “National security” concerns triumphed over civil rights and civil liberties, because once again communities of color were treated as the suspicious other. My congressman, Jim McDermott, was an exception, as was our only black county councilmember, Larry Gossett. When I began organizing rallies outside mosques to protest the lack of due process for Muslim Americans and for Arab Americans who were being secretly detained and deported in the middle of the night, it became even more difficult to find elected leaders who would stand with us.

Our message fell on more sympathetic ears with locally elected officials. Although our city council knew very little back then about the circumstances of immigrants, they were much more open to the concerns of their diverse constituents. There were organizers on the council like councilmember Nick Licata who believed in people’s voices being at the table. Working with him, we passed one of the first ordinances, now called Sanctuary City ordinances, to prevent local police and city officials from asking about immigration status.

I had to explain for too long, too hard, and too loudly about what seemed like obvious problems to me.

The higher the elected official rose, the harder it seemed to get them to take a stand that might be seen as controversial. Back then, immigration reform was far from popular and it took years to convince our congressional delegation to boldly embrace humane and just immigration reform. It was only after I worked to organize the hearing with Senator Ted Kennedy in Washington, DC, that we were able to move one of our own senators to participate in a Justice for All town hall in Seattle.

My first light bulb moment about how to build greater political power for immigrants came in 2004. I was frustrated that the immigration issues we were focused on were not getting the attention they needed. Too few elected officials were willing to work to reverse policies like Special Registration, speak out against Islamophobia, or champion immigration reform.

I realized that elected officials seemed to care only about two things: first, money from donors and corporate lobbyists, which seemed to work to block courageous votes or action, and second (sometimes in this order), the votes of their own constituents. We didn’t have money, but couldn’t we organize existing voters, maybe even register new voters? Could we mobilize those voters to build the political power of immigrants and demand that politicians respond to our communities’ needs?

The truth was too many immigrants had lost faith in government and they didn’t vote. Like me, they didn’t see elected officials who represented them, who looked like them, or who understood their lives. Some even just sat out the elections, because they felt cynical about the people who were running and their desire to really serve them and make a difference. Many had also not received the kind of civic education that even allowed them to understand the basic processes of voting in the United States, which are far from simple for a new American in this country. Could we get them to care about and trust the power of the vote?

I decided to try an experiment: Hate Free Zone partnered with the brand-new Seattle chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) to implement a new pilot project designed to get Muslim Americans educated about and registered to vote, and then encourage them to turn out to actually vote. It was a small project, implemented just months before the 2004 election. We went into mosques and community centers and registered some three hundred new Muslim American voters. They were well aware of the terrible things that were happening to their communities in the years after 9 / 11, and so our job was to convince them that their voices and their votes would make a difference. This required a lot of conversation, education, and ultimately mobilization to get them to the polls when it was time to vote. In the end, 98 percent of them voted!

Armed with a successful pilot project, we began a much larger voter registration drive in 2005 and 2006, ultimately registering over 27,000 new American citizens to vote. It was the largest voter registration drive in the history of the state, and it caught the attention of elected officials. At approximately the same time, we began a big statewide campaign to push Washington’s governor Christine Gregoire to establish a New Americans Policy Council and to fund a massive program to help legal permanent residents who were eligible get their citizenship. Because of our voter registration work and growing political power, in 2008, we were able to establish the first-ever state level policy council and get funding for the New American Citizenship Program. If I had ever questioned what it really means to build political power, I could see it working now.

And yet, we still were not where we wanted to be. For example, in spite of all our work on immigration, we fought frustrating battles to get elected officials to come out and support us, particularly against unjust and cruel enforcement measures against immigrants. I’ve come to believe that the term “progressive” really just refers to the people who advocate for justice on an issue first, before it is popular. Back then, even some of our Democratic congressmembers who are out front on immigration issues today were not particularly strong on those issues then, sometimes voting for anti-immigrant bills or just staying silent at critical times when we desperately needed their voice and leadership.

All of this contributed to my own distrust of elected officials and kept me away from the idea of running for office myself. Community members would often mention the possibility to me, but it is notable that nobody from the Democratic Party machine asked me to run. I was not part of “the system.” I was pushing people hard for what I believed was necessary, and I was not wealthy or well-connected—all viewed as negatives to the party machine that had a lot to say about who would run for office, or at least who would get the needed early support.

I did have some heroes in elected office: Jim McDermott, who had been so influential in the start and success of Hate Free Zone in the early days and Congresswoman Barbara Lee, for her vote against the 2001 Authorization of Military Force in Iraq, for starters. I had also read Shirley Chisholm’s book, Unbought and Unbossed, with rapt attention. Later, in 2013, I met Stacey Abrams, who at the time was the minority leader in the Georgia State Senate. She talked to me about how important it was for us as women of color to run for office and to be in office.

It was months after that conversation, in late 2013, when the longtime state senator for my district announced that he would not seek reelection. Immediately, a whole host of candidates declared themselves. Some friends reached out to me and asked if I would consider a run for the seat. My state legislative district at the time was the largest minority-majority district in the state, and I had the distinct honor to live in what was often cited as the most diverse zip code in the nation. But I said immediately that I was not interested. Most of my recent work was at the federal level, with Congress, and the state legislatures at the time were not the focus of much activist work. I also just wasn’t convinced that elected office was for me.

But over the next month or two, as I watched the wide slate of candidates who stepped up to run for the open state senate seat talk about why they were running, it slowly became clear to me that I had been thinking about elected office all wrong.

As activists, we were critical of the way government worked—and yet, at the same time, we turned our noses up at the idea of running for office ourselves. I realized that in our own judgmental way, we were ceding important political space to others, instead of occupying it ourselves. What if we began to think about running for office as a way to organize more people, to connect people to the government, to bring organizing from the outside to the inside, to have the proverbial seat at the table but use it to lead not just follow?

It was the beginning of the formation of my new theory of change.

For years, I had believed that if politics is the art of the possible, then our job as activists is to push the boundaries of what is possible—but from the outside. Why couldn’t that pushing also occur from the platform of an elected office? An elected office could be the biggest organizing platform yet! Perhaps part of the problem was that there weren’t enough of us on the inside to do the pushing, and I realized you really needed people working from both the inside and the outside for change to happen as quickly as necessary.

I was starting to see that elected office could be a new platform for building a base of supporters, systematic organizing efforts, and progressive policy development. We don’t get a more responsive government unless we systematically run organizing campaigns to change the way government works. We don’t understand what we are really dealing with or how to change it unless we know exactly how it works now. We don’t get a more powerful and progressive group of elected officials unless we insert ourselves into the equation. And we can’t organize on the inside if we have no organizers on the inside. In other words, we don’t get a more representative government unless we run it ourselves. As my experience serving in an elected office would confirm, you really need to organize on the inside just as hard as you organize on the outside. We needed both.

I was now ready to try out my new theory of change and, to do it, I decided—in just a week of talking to family and friends—that I would run for the Washington State Senate open seat. Many of my activist friends thought I was crazy. SEIU 775 president David Rolf told me it would be a waste of my skills. My immigrant friends were mixed—they pursed their lips and said they needed me to advocate for them in the field, not in Olympia, the state’s capital—but then they also said it would be deeply meaningful to them to see someone like me in elected office representing them. Other organizer friends said the sacrifices were too manystate office paid hardly anything and was supposedly part-time. However, the reality was that being a senator was actually full-time work and you had no time to hold another full-time job. Many incumbents had sweet deals where their employers paid them full-time salaries, despite spending months each year in Olympia. We movement leaders transitioning into state legislatures had no such cushy rides.

I listened to all of the advice and comments, but in the end, I decided it was an opportunity for me to try out my theory of change, to find out if elected office could be another important organizing platform that we could utilize to build our movement. I told myself what I tell so many other people who agonize over life choices: if I didn’t like it, I could always leave. For now, it was time to get to work and win the campaign.

__________________________________

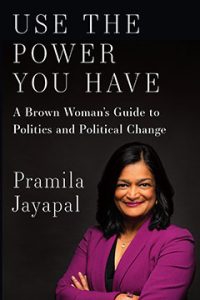

Excerpted from Use the Power You Have: A Brown Woman’s Guide to Politics and Political Change by Pramila Jayapal. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, The New Press.

Pramila Jayapal

Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal represents Washington’s 7th District, which encompasses most of Seattle and surrounding areas. The first Indian American woman in the House of Representatives, Jayapal has spent nearly thirty years working internationally and domestically as an advocate for women’s, immigrant, civil, and human rights. The author of Use the Power You Have (The New Press), she lives in Seattle, Washington.