Poverty, Anxiety, and Gender in Scottish Working-Class Literature

Douglas Stuart Offers a Reading List in Response to

"The Glasgow Effect"

I grew up in a house without books, which was not unusual for the time or the place. The working men who surrounded me bent steel for a living, they built fine ships, or traveled miles into the earth to hack away at coalfaces. We sons took after our fathers. We kicked things—first it was footballs, then it was each other—and as we grew, we had little time for books. We sought apprenticeships or we learned trades. We were proud, we were useful.

But the ruling conservative government cared nothing for the honest, working poor. They set about privatizing most manufacturing, removing all support for nationalized labor. In doing so Margaret Thatcher decimated the working man. Her policies swept all heavy industry from the west coast of Scotland in the span of a single generation and did it with all the disregard of a government separated by distance and several social classes. Steel, ships, coal, all gone. The men had nowhere to turn and they became chronically unemployed. They were emasculated and sent by a woman (no less) to rot away their lives into rented settees.

The west coast of Scotland in the 1970s and 80s was a place of mass unemployment, sink estates and pervasive blight. The absolute lack of opportunity ushered in decades of drink and drug abuse that saw life expectancy drop to some of the lowest levels in Western Europe. “The Glasgow Effect,” describes the invisible factors that reduces a man’s life expectancy based on the housing scheme he lives on. Even today, a man from the precarious under-class of Glasgow will die approximately 11 years before a man who still has a job, who still has a little hope.

It’s hard to find a silver lining amongst this deprivation, but if there is one, perhaps it is that these conditions laid the fertile ground that would germinate some absolute masterpieces of the written word.

The joy of reading came to me much later in life. When you grow up amongst these conditions it can be hard to find the peace to be able to turn inwards into books. Books are an escape, yes, but it was only when I started to see my own world, my own people on the pages before me, that I discovered the true power of words. Books are a window, a dream, an education; but sometimes, and as importantly, they are a record that we, and those like us, are here. These are the books that make me feel seen.

*

How Late It Was, How Late (1994) by James Kelman

This is an unapologetic, unflinching book, that has been described by some as comfortless. Personally, I find this to be high praise, rather than a point of criticism. Sammy, a vexsome Glaswegian drunk, has just woken up in a police cell after a multi-day bender. He wakes up completely blind, and what happens next only gets stranger as he tries to find his way home, cope with his new disability, and locate his missing girlfriend.

The Glaswegian patter rattles in your mind as you journey across the city with Sammy, and deeper into his blindness and paranoia as he deals with inefficient bureaucracies and malevolent policemen.

When I first came to this book I was both thrilled and surprised that it had won the Man Booker Prize. It famously split the judging panel between those who saw the genius that it was and those who walked out in protest because they found it low, vulgar, obscene in its everyday foul dialect—literally “literary vandalism.”

As a Scottish-American writer, the criticism of this book muted me. On my worst days I can feel like I am not worthy; that I’m not educated enough, that my regional tongue is not sufficiently elevated to be committed to the page. It’s then that I think of this book and I’m reminded of its power. Kelman wrote every word in truth, and he did it brilliantly. It’s an unforgettable piece of fiction.

The Trick Is to Keep Breathing (1989) by Janice Galloway

“I have lost the ease of being inside my own skin.” Joy—a misnomer—is crumbling. She is grieving the death of her mother and the accidental drowning of her married lover while succumbing to increased isolation and depression fueled by anorexia and alcoholism.

The first time I read this book I was too young to appreciate its psychological realism. It is a shocking and darkly funny portrait of mental illness, loneliness and waste. It won the Whitbread First Novel prize because Galloway writes with a startling clarity. I am in awe of the closeness with which Galloway rubs at every raw feeling.

There is a rich seam in Northern fiction of the struggling soul, the alcoholic. But he is often male, and in his lowness we can empathize with him, and being a man we ultimately forgive him. It feels perverse to watch a woman go through the same self-destruction. It’s wrong, but you somehow feel more disappointed in her struggle. But that is a harmful taboo.

I grew up around disintegrating women, not just inside my own home, but for streets and streets around. In the early ’80s there always seemed to be a mother, a wife, collapsing under the suffocating weight of having nothing better to look forward to. This is the book that encouraged me to commit to my character of Agnes Bain at her worst, because Galloway presents her own flawed heroine and never once looks away. The author shows us how close to disaster we all are, how grief and loss can wreck us in a moment; how everyday can be a struggle when life becomes too flat to care.

Young Adam (1954) by Alexander Trocchi

I admire this novel because Trocchi gave us an irredeemable hero and still managed to make us care for him. Joe is a total user. He is a bargehand, ferrying coal between Glasgow and Edinburgh. We see him find the body of a young woman floating in the canal and come to learn that he might know more than he lets on. When he seduces his boss’s wife and then cruelly discards her, we are painted a portrait of a selfish man who is losing his sexual charisma—when he had little else besides.

Underneath the story of a dead girl is the tale of survival. It shows us how little value can be placed on others, when you feel like your own life is not worth much at all. It is about how people use one another in order to save themselves; and also how people let others fall to ruin in the hope that they may be spared a little while longer. It’s a lovely portrait of a coward.

All the characters in Trocchi’s novel seem destined to unhappiness, being unfeeling, self-serving creatures. It is a claustrophobic study in how men and women can use each other, a frank look at casual sex regardless of finer feelings. The author shows us how sex is a currency. How when you have nothing else to barter, then coupling can take on a desperate, mercenary need.

Trainspotting (1993) by Irvine Welsh

I hated Trainspotting in the 90s. As a boy who grew up with an addict for a mother, I couldn’t bear what I saw as the glorification of junkies and drunks. It was an earth-shaking cultural moment and then to see middle-class university students go on a poverty safari and ape the skag-chic that was decimating my hometown was galling to me. I hated it. But in the end the failing was all mine. This book is a classic for all times. It is excellent.

We follow a clutch of Edinburgh junkies and loose friends as they weave together in an out of different stories, some comedic, some utterly tragic. We are drawn to the protagonist Mark Renton, but the smaller scenes that were left on the page and were not in the movie are where the real magic happens for me. Renton is a gallus character: nihilistic, selfish, but deeply endearing as he rails against conformity, as he destroys himself even though he has so much to live for.

As HIV starts to sweep the city, we get clear-eyed insight into the cost of addiction and the randomness of its scourge. Despite the bleak subject matter this books sings, and in the darkest moments it shines with humor. Every character here is alive—unlikeable or severely damaged perhaps—but they are still more alive than most.

Gentlemen of the West (1984) by Agnes Owens

Agnes Owens is one of the most detailed observers of working-class life that I have ever read. Owens was declared “the most unfairly neglected of all living Scottish authors” and although I agree, I also think she was the most special, because her writing brings a tenderness, and a kindness to a hard, industrial landscape that is usually dominated by men.

This, her most famous work, tells the episodic tale of Mac, a young Glaswegian bricklayer, who is struggling to find direction in a city blighted with unemployment. Mac reminds me of all the young men on my government housing scheme, and how when everything seems so hopeless, it’s human to ask, why would you even bother?

Mac’s narrow life moves between obliteration down at the local pub and the nagging claustrophobia of his cantankerous mother’s small tenement flat. It’s a book that is often sad, a little odd and terribly funny all at the exact same time. The chorus of characters shine darkly.

Where other books in this milieu can descend into masculine violence and sexual anger, this is an intimate and dignified story. It’s a window into how mothers must have felt when they saw unemployment rocket to a crippling 28 percent and saw their husbands and sons with nowhere to turn. It is clear that Owens—who is a self-taught writer—brings all of her own experience to these pages. As Alasdair Gray put it; “life has taught her to face facts and mention them in the fewest possible words.” Her books can be hard to find in today’s world, but if you do, I promise you will be rewarded.

Morvern Callar (1995) by Alan Warner

Set in a West-coast port town, Morvern Callar is a shelf-stacker in the local supermarket who wakes one morning to find her boyfriend has committed suicide. She changes the name on his unpublished manuscript and then hides his festering body. When the stolen manuscript becomes a success and the advances start to pour in, Morvern takes her one chance to escape the run-down town.

Written in spare prose that has an insistent beat to it, this book will resonate with anyone who knows the sinking feeling of being stuck in a small town/small life. What I find most surprising about the novel is how it takes the horror of the death and dismemberment and deals with it matter-of-factly, because at the end of the day sometimes coping with a dire situation is all you can do; grief and anguish are luxuries not everyone can afford.

I can relate to Morvern’s hedonism during the bleakest of times: how she longed for the obliteration of drink and parties, or the simple joy of sun on her skin after a life spent in a damp grey town. I have known a hundred Morverns—perhaps we all know people who are stuck—so when I saw a woman seizing her one horrible chance to escape her dire situation, it was hard not to cheer her on.

His Bloody Project (2015) by Graeme Macrae Burnet

The author shines a light on the hard-scrabble existence of subsistence crofting that upends the usual romantic, peaceful image of the Scottish Highlands. He shows what rural life was truly like post the Highland Clearances; which were the enforced removal of tenants from farming land by absentee landlords, in order to allow sheep to graze for higher profit. It was a mass eviction, which resulted in one of the largest, and mostly unheard of, refugee crises in European history.

Set in 1869 the story is centered around a brutal triple murder in the Scottish Highlands. The anti-hero, Roderick Macrae, is a bright boy who cannot escape his crofting community because he cannot be spared from working the intractable land. His isolated village is suffocating him, with its small slights and petty abuses of power.

Longlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize, at first pass this is a literary thriller, a crime procedural of sorts. It’s also a fascinating class study, of how even at the bottom of society, people still struggle to create a hierarchy no matter how minute the distinction. As a society we are returning to a time when right-wing politicians bark at the poor to help themselves. This is a book that should remind us that poverty is a trap; that hardworking people cannot always escape the grinding workloads of their day-to-day in order to set their sights on the far horizon.

Lowborn (2019) by Kerry Hudson

Infuriatingly, around a third of all children living in the United Kingdom today still live in poverty. This brave nonfiction book charts the experiences of the author growing up in some of the most deprived housing estates in the UK. Raised by a single mother gripped by addiction, the author scored eight-out-of-ten on the government’s “Adverse Childhood Experiences” scale that measures childhood trauma.

As Hudson revisits the housing schemes and hardships of her childhood, she does it with rare grace, a desire to understand without anger or judgement. As a writer who was fortunate enough to have access to a good education, I am now closer to the middle class than the underclass that I grew up in. This in itself can feel like a betrayal of those I love, those who made me who I am.

It’s always hard to write about growing up poor. It’s a delicate subject to capture without being perceived as condemning the circumstances or the other people who were present. But there is definitely a need to be honest about how brutally hard it is, how detrimental it is to children, and Hudson does this clearly and with well-considered feeling. Her book is a masterclass in empathy. As the author herself states: she was always proud to be working class, but she was never proud to be poor.

__________________________________

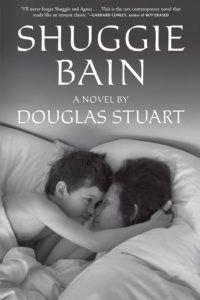

Douglas Stuart’s debut novel Shuggie Bain is available from Grove Press.

Douglas Stuart

Douglas Stuart was born and raised in Glasgow. After graduating from the Royal College of Art in London, he moved to New York City, where he began a career in fashion design. Shuggie Bain is his first novel.