I first heard of the Belgica expedition in the spring of 2015, while procrastinating at my desk at Departures magazine. I was flipping through the latest issue of The New Yorker when I found a headline that caught my interest: “Moving to Mars.” It was about an ongoing experiment taking place on Hawaii’s Mauna Loa—about as close as the earth gets to a Martian environment—in which six volunteers lived in isolation under a geodesic dome for a NASA-funded study on team dynamics, in preparation for eventual missions to the Red Planet.

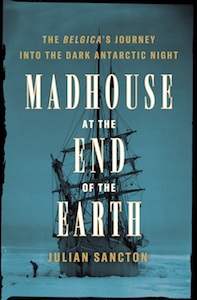

In classic New Yorker fashion, the author, Tom Kizzia, backed into the story. The first few paragraphs were about an expedition that took place 120 years ago, involving the first men to endure an Antarctic winter. Kizzia mentioned the “‘mad-house’ promenade” around the ship, a phrase that immediately jumped out at me. I was intrigued to find out what possible connection there might be between the Belgica and far-flung space exploration. But even more fascinating to me was the character of the physician, Frederick Albert Cook, known as one of America’s most shameless hucksters, who through relentless ingenuity nevertheless managed to save the expedition from catastrophe.

I’ve always been drawn to heroic antiheroes: Sherlock Holmes, Butch Cassidy, Han Solo. When I looked further into Cook’s story and learned that he lived out his final days in Larchmont, New York, in a house I pass every time I walk my dog, it felt like a sign: there was no way I wasn’t writing this book.

Thus began a five-year obsession that took me across the world, from Oslo to Antwerp to Antarctica, on the trail of the Belgica and her men. The narrative that unfolded before me, through diaries and other primary sources, turned out to be far richer than the simple good yarn I’d imagined at first. The expedition shaped two future giants of exploration, one rightly revered, Roald Amundsen, and one unfairly maligned, the aforementioned Cook. It culminated with an epic breakout from the tenacious Antarctic pack ice that, in its scale and ambition, rivals the greatest man-versus-nature struggles in history and literature. And its legacy proved much more consequential than the mere survival of (most of) its men.

One of the challenges I faced in recreating a journey that took place so long ago, and in such extreme isolation, was getting access to the sensory quality of the experience. Not just what happened day to day, or what coordinates the ship reached along her circuitous drift, but what it must have been like for the men aboard, both to discover such splendors and to endure such hardship. To my delight, it soon became apparent that the Belgica voyage was among the most well-documented polar missions of the heroic age, in which no fewer than ten men kept detailed diaries or logs (even though one was later burned).

The first major breakthrough in my research came in the fall of 2018, when the filmmaker Henri de Gerlache, the commandant’s dashing great-grandson and an explorer in his own right, invited me to his family’s beautiful estate in the countryside outside Ghent. There, he pulled out four large hardbound volumes—Adrien de Gerlache’s log from the expedition.

As Henri and I paged through the gently weathered books, we became engrossed, as if we were reading an adventure novel. To our right, under a grand staircase, was one of the Belgica’s sledges. As I ran my hand along its splintered edge, I told myself that it might have been one of the sledges Cook and Amundsen used on their death-defying treks across the pack. The story came alive to me that day.

The following morning, I headed to the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels, a rather homely mid-century modern building where much of the Belgica’s archives are held. I had an appointment with Olivier Pauwels, curator of recent vertebrates. Wearing a navy sweater-vest stretched over his paunch, the scientist exuded the wry world-weariness of a career civil servant, which failed to entirely obscure his abiding passion for the animal world. He threw on an ill-fitting white coat and led me down cluttered, decrepit hallways into the bowels of the institute’s vast collection.

Its legacy proved much more consequential than the mere survival of (most of) its men.Zoological specimens accumulated over the institute’s 175-year history are stored in a seemingly infinite, white-tiled labyrinth lined with wooden drawers and compartments, each one containing multiple individuals of a single species, either stuffed, jarred, or reduced to a labeled pile of bones. The aisles teemed with oversized taxidermy, a magic-realist menagerie organized with no apparent rhyme or reason, as if the animals were roaming freely. Twisting past a yak and a flock of flamingos, Pauwels at last arrived at the item number indicated on his clipboard. He slapped on a pair of blue latex gloves.

“Back in the day, these specimens were preserved in arsenic to ward off mites and insects,” he said. The poison is still lethal 100 years later.

Pauwels opened a large drawer and pulled out an emperor penguin captured and euthanized during the course of the Belgica expedition, one of many brought back to Belgium. Its eyes were missing and its feathers had lost their sheen, but the four-foot-tall bird, standing with exemplary posture, filled me with awe: this was the closest I’d get to meeting a member of the expedition. I wondered which of the Belgica’s men had killed it, and I tried to imagine how they had felt in that moment. I told myself that its meat had helped save their lives.

Over the next few hours, Pauwels guided me through much of the Belgica’s trove. We saw many more stuffed penguins—emperors, gentoos, Adélies—as well as seal bones and deep-sea fish preserved in jars of ethanol.

Pauwels took me to the invertebrates floor and showed me a slide containing a single, barely visible larva of Belgica antarctica, the only strictly terrestrial animal native to Antarctica, which the expedition’s Romanian naturalist, Emile Racovitza, discovered. I was transported instantly to a rocky shore along the Gerlache Strait, in January 1898.

Beside me, Racovitza is hunched over a patch of lichen, brows furrowed, magnifying glass in hand, picking out insects. In his address to the Royal Belgian Geographical Society on November 18, 1899, Georges Lecointe made it a point to emphasize that the expedition brought back much more than “one overwintering and two deaths.”

The contribution of the Belgica’s scientists to Antarctic scholarship cannot be overestimated. Racovitza cataloged thousands of specimens from hundreds of species of plant and animal life—moss, lichen, fish, birds, mammals, insects, pelagic organisms—many of them new to science. He documented penguin and seal behaviors in detail. His colleague, the Polish geologist Henryk Arctowski, discovered the deep abyss that lay between Tierra del Fuego and Graham Land. And together with his compatriot Antoni Dobrowolski, he compiled the first full year’s worth of meteorological and oceanographic data south of the antarctic circle. It would take the Commission of the Belgica more than 40 years to sort through and analyze the expedition’s observations. Collectively, the scientists’ findings form the basis of our understanding of the frozen continent, and all three men went on to distinguished careers.

The legacy of the Belgica voyage goes well beyond its scientific harvest. The mission was among the first truly international expeditions of the modern era, certainly the first to the polar regions. That achievement must be credited to de Gerlache, who despite his patriotism and military background was a pacifist at heart. He defied his compatriots’ expectations that he hire only Belgians, instead recruiting the best men he could find, regardless of their citizenship. At a time when Western powers were racing to subdivide the world—a jingoistic frenzy that would lead to a world war within two decades—de Gerlache established a standard of global cooperation that persists in Antarctica to this day, unlike in the oil-rich and increasingly contested Arctic.

It is significant that de Gerlache declined to stake any claim of Belgian sovereignty over the strait that today bears his name. (Unlike, for example, James Clark Ross, who in 1841 formally took possession of Victoria Land on behalf of Great Britain.)

In his belief that science transcended politics and borders, the commandant set the stage for more than a century of peace in Antarctica. Thanks to de Gerlache, and to his son Gaston, who led his own Antarctic mission in 1957–58, Belgium is a signatory to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, which forbids all military activity on the continent. A subsequent accord, the Madrid Protocol of 1991, protects Antarctica’s animals and natural resources against all forms of exploitation. Antarctica’s example, in turn, prefigured such grand scientific endeavors as the International Space Station, where astronauts from rival nations collaborate peacefully, irrespective of terrestrial squabbles.

Where the Belgica was perhaps most influential was in illuminating the devastating physiological and psychological toll of far-flung exploration, which Frederick Cook so diligently chronicled. The science of the past 120 years has borne out the doctor’s instincts.

Clinical studies on scientific and support personnel at year-round Antarctic bases have consistently yielded reports of physical and mental symptoms similar in kind, if not degree, to those experienced by the men of the Belgica: irregular heartbeat, fatigue, hostility, depression, memory loss, confusion, and cognitive slowing. There are also frequent accounts of a dissociative fugue state that leaves people looking blankly and unresponsively into the middle distance, known colloquially as the “Antarctic stare.” One physician defines it as “a twelve-foot stare in a ten-foot room.” This perfectly describes Adam Tollefsen’s demeanor in the early stages of his madness.

Cook referred to these symptoms collectively as “polar anaemia.” Researchers today use the term “winter-over syndrome,” but it’s essentially the same thing. A prevailing theory suggests the syndrome is a form of hypothyroidism, which is associated with depression and atrial fibrillation and could thus account for both the “cerebral symptoms” and the “cardiac symptoms” that most concerned Cook before scurvy took hold.

Thyroid hormones help the body regulate temperature and set its circadian rhythms. It’s not difficult to see how extreme cold and the prolonged absence of sunshine might throw the system off. This is just a hypothesis. The causes of the syndrome remain puzzling more than a century after Cook first described it. Scientists believe physiological factors tell only part of the story. Stress due to confinement, isolation, boredom, unvaried food, and the psychosocial pressures that inevitably arise among small groups of people contributes in no small part to the psychological and cognitive symptoms experienced by Antarctic personnel.

But in emphasizing the likelihood of a connection between winter-over syndrome and what is now known as seasonal affective disorder—a variation in mood that correlates with the dwindling of daylight hours—physicians today support Cook’s belief that light plays an essential role in human welfare. His wild idea to have his ailing shipmates stand naked in front of a blazing fire is the first known application of light therapy, used today to treat sleep disorders and depression, among other things.

Though Cook is remembered today—if he is remembered at all—as the charlatan who lied about reaching the North Pole, he may yet find redemption in the next phase of human exploration: manned missions to Mars. The psychological challenges of such a voyage are every bit as daunting as the technical ones. As Roald Amundsen put it, “The human factor is three-quarters of any expedition.”

Among the greatest threats future travelers to Mars are likely to face is an interplanetary version of winter-over syndrome. The unknown icescapes around the earth’s poles—particularly Antarctica—seemed as remote and forbidding to 19th-century explorers as Mars does to us now. Not surprisingly, NASA has sought to draw lessons from polar expeditions, the closest thing in human history to a precedent for extended space travel. This was the context in which the New Yorker article I read in 2015 mentioned the Belgica.

For the past three decades, NASA has worked closely with Jack Stuster, a behavioral scientist and anthropologist best known for his 1996 book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Exploration. The Belgica is among Stuster’s main case studies. Expeditions in which everybody died yield few practical lessons. The same goes for those—like Amundsen’s South Pole run in 1911—that went off with nary a hitch.

Far more instructive are those, like the Belgica, that encountered significant adversity and overcame it. Cook’s observations, his warnings, his ad hoc remedies and recommendations, have directly influenced NASA operating procedures.

In his surveys of astronauts, for example, Stuster found that space travelers tire easily of their food and crave something crunchy. This recalls Cook’s complaint, “How we longed to use our teeth!”

Taking a cue from the doctor, Stuster therefore suggests sourcing the widest possible variety of food. More generally, he encourages Mars-bound doctors to emulate Cook’s resourcefulness and his insistence on maintaining a cheerful attitude.

“That’s who I think of when I’m writing about the physician role,” Stuster told me. “I think of Frederick Cook.”

When we do reach Mars, we will, in some small part, have Cook to thank.

When I told a friend of mine, an editor whose advice I value dearly, that I planned to visit Antarctica for this book, he said, “What for? Why don’t you just rely on the diaries?” I didn’t know how to answer. The book, after all, is not a travelogue. My friend suspected I wanted to justify a bucket-list trip as a business expense. He was only partly right. I didn’t know what I would find there, but I knew that, no matter how detailed the diaries were, I’d never be able to satisfactorily reconstruct the sights, sounds, and smells of Antarctica without experiencing them myself. I contacted the Chilean company Antarctica21 and splurged on a ticket for a weeklong cruise, departing mid-December 2018. Like de Gerlache and his men, I left from Punta Arenas.

Unlike them, I flew over the tempestuous and notoriously nauseating Drake Passage by plane, a two-hour flight that landed at the Chilean-Russian research base on King George Island. From there my fellow cruisegoers and I boarded the Hebridean Sky, the 70-passenger cruise ship that would take us across the Bransfield Strait to the channel discovered in 1898 by the men of the Belgica.

The environment that the Belgica’s men explored is fast becoming a lost world.This was not a special concession to me. The weather around the frozen continent is so unpredictable and so potentially dangerous that cruise companies never guarantee an itinerary ahead of time and instead defer to their ship captains to survey the winds and currents and determine the route each day. But the first-choice destination of virtually all the Antarctic cruises leaving from South America is the Gerlache Strait, one of the most sublime and photogenic places on the planet. Throughout my weeklong journey, I was struck by how familiar this landscape seemed to me. Save for the bluish tint of the ice, it looked virtually identical to Cook’s black-and-white photographs. But as was soon made clear to me, the environment that the Belgica’s men explored is fast becoming a lost world.

On a misty afternoon halfway into my trip, a handful of passengers and I zipped across the channel on a Zodiac inflatable, cutting through light snowfall. We arrived in the lee of Danco Island, named after the Belgica’s second victim, Emile Danco. Penguins and humpback whales put on a show for us, as they did for the men of the Belgica. At first glance, nothing appeared to have changed here in 120 years. But a closer examination told another story.

At the helm of the Zodiac was Bob Gilmore, a geologist by training, hired to educate guests in the science of the Antarctic. As part of his job, he took measurements of temperature, salinity, and phytoplankton populations in the waters of the Gerlache Strait, which he communicated to academic and government institutions that monitor changes in the area but don’t have the luxury of visiting regularly.

Gilmore handed me a small tube and instructed me to fill it with seawater. I told myself this was the same work Racovitza and Arctowski performed here in the first blissful weeks of 1898. Gilmore squeezed a solution from an eyedropper into the sample to kill the organisms within it before the zooplankton had a chance to devour the phytoplankton. He screwed the top back onto the tube, the contents of which he would analyze back aboard our ship.

For the previous few years, the changes Gilmore had observed in these samples had been subtle but sobering. Warmer air temperatures had sped up the melting of glaciers. The increased flow of fresh water, in turn, had decreased the salinity of the strait. As a result, the structure of phytoplankton communities had shifted. The large diatoms that krill prefer to eat were being replaced by smaller diatoms that are better adapted to the less salty water. This trend has potentially catastrophic consequences: As the larger diatoms disappear, so might the swarms of krill that feast on them. As the krill go, so will the rest of this delicate ecosystem.

The very concept of Antarctic tourism is in some ways disheartening.I was one of more than 50,000 people to visit Antarctica in the austral summer of 2018–19. It wasn’t lost on me that my very presence here—in particular, the emissions from the Hebridean Sky and dozens of ships like her—contributed directly to the endangerment of this magical place. The growing popularity of Antarctica as a tourist destination is understandable: for those who have the privilege to be able to visit, the experience is awesome and humbling. It is the last truly wild place on earth. Yet the very concept of Antarctic tourism is in some ways disheartening: thousands of people a year are drinking martinis and singing karaoke on the same waters that de Gerlache and his men navigated with such trepidation when they were the only people on the entire continent.

Powerful icebreakers and communication technology have made it safer to travel here. But it would be wrong to assume that the Antarctic has gotten any less menacing. The menace has simply transformed. The continent remains just as hostile to human life as it was in the age of de Gerlache and Scott and Shackleton. Only now its grasp extends well beyond the explorers foolhardy enough to venture into the ice.

For millions of years, Antarctica’s glaciers have flowed into the sea, calving icebergs at a slow and sustainable rate. In the past few decades, that rate has rapidly increased as temperatures in the region have shot up to alarming levels. During a heat wave in February 2020, they reached a record 69 degrees on Seymour Island, at the tip of Graham Land. The less isolated Arctic is a harbinger of how climate change might soon affect the southernmost continent.

In 2007, the Northwest Passage, which Amundsen took three years to muscle through aboard the tiny Gjøa, became navigable for the first time. It is expected that the North Pole will be clear of summer sea ice by 2050.

Antarctica’s ice contains at least 80 percent of the fresh water on earth. If all of it were to melt, sea levels everywhere would rise by up to 200 feet, drastically redrawing the world map. This may not happen in the near future—the Antarctic ice cap is more than a mile thick in places—but any sustained amount of warming will lead to sea-level rise that will obliterate coastal communities and cause incalculable suffering. The continent is a coiled spring loaded with tremendous destructive power.

If Poe and Verne were writing today, this is the nightmare scenario that would capture their imaginations. They would be drawn not to the ends of the earth, but to the end of the earth. Just as the Belgica’s men answered the call of fiction to elucidate the mysteries of the Antarctic, it is now up to scientists and explorers to blaze the path ahead.

May they have the audacity of Adrien de Gerlache, the fortitude of Roald Amundsen, and the gumption of Frederick Cook. Like the Belgica, we have sailed heedlessly into a trap of our own making, but if that expedition proved anything, it’s that we need never resign ourselves to doom. Audaces fortuna juvat!

__________________________________

Excerpted from Madhouse at the End of the Earth: The Belgica’s Journey Into the Dark Antarctic Night. Used with the permission of the publisher, Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Julian Sancton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.