Poetry in Three Dimensions: Sarah Ruhl on Bringing the Words of Max Ritvo to the Theater

“Let this all be poetry!”

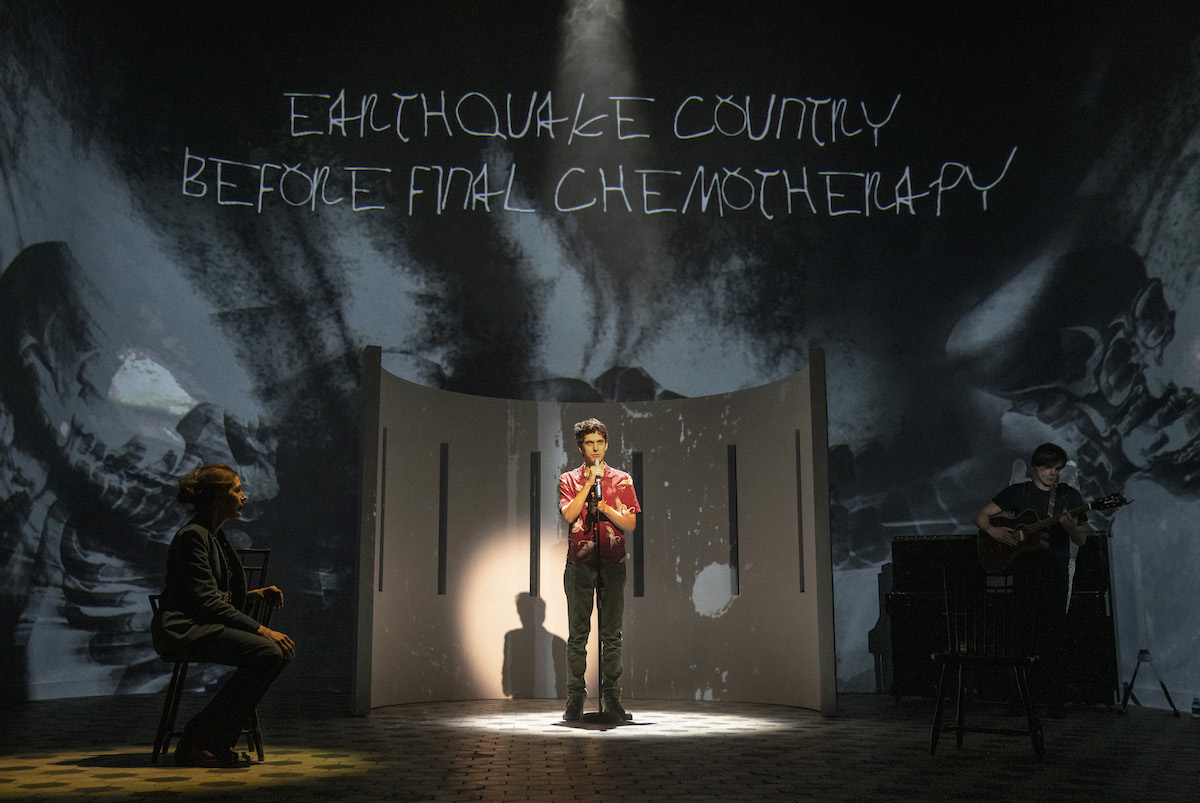

Production photo by Joan Marcus.

I first met the poet Max Ritvo when he was a Yale senior in my playwriting workshop. He had a luminous quick-silver mind, an open heart, a rare and unmistakable poetic gift, and a wild sense of humor. That fall, he also had a recurrence of Ewing’s Sarcoma, a pediatric cancer. He worked incredibly hard to graduate from college while undergoing chemotherapy, writing poetry madly all the while. After his graduation, we wrote letters back and forth. Over the next three years, we became close friends and poetry confidants, and discussed everything from the afterlife to pop music to child-rearing to our enduring love of soup.

Max and I continued to share poems and letters as he went on myriad experimental trials, got married, and got his MFA in poetry. Meanwhile, I continued to raise three children with my husband, teach, and write plays. Max and I planned to make our letters into a book; sometimes we argued about how to arrange them. He argued for thematic arrangement; I argued for chronology. Sometimes I thought Max didn’t want a chronological arrangement because of the void looming at the end of the book.

Max died when he was twenty-five. He left behind a family in mourning, a young widow, crowds of literary admirers, legions of friends, and several teachers who he flipped from teachers into students in short order. He also left behind his brilliant first book of poetry, Four Reincarnations, which Milkweed editions had rushed to press, so that he could hold the galleys in his hands. Surely, he is the only poet to have had his debut collection sell as many copies as the Odyssey the day it came out.

*

After I finished Letters from Max, the book Max and I had started together, it never occurred to me that the material could also be a play. It felt too quiet, too personal, too beyond representation. How, I thought, could any actor pretend to be Max? That felt wrong, weird, and worrisome. But the more I did public readings of the book Letters from Max (often having another poet or actor read Max’s letters), the more I found the process of dialogue brought Max’s words back into the present tense. I loved hearing his poems aloud with an embodied voice. And the more I heard Max’s poems aloud, the more I craved to hear them in full-throated three dimensions.

As it turns out, in this first production of Letters from Max at the Signature theater in New York, we ended up casting two different actors in the role of Max who alternate performances, and on successive nights, each actor accompanies the other Max musically. One actor plays the piano: the other plays guitar. I felt that having two actors alternate and originate the role of Max in this first production created humility around the idea of who can play a single role, and underscores the idea that Max’s legacy is bigger than any one actor. I wanted the production to channel emotion and language, rather than depending on imitation or mimesis. I wanted them to channel voice.

As I worked on the strange alchemy of turning poems and letters into a play, I was mindful that in opera, arias stop time, whereas the libretto moves time forward. Max, because his poems do what poetry can do best—is able to stop time. It took much trial and error for me to see how many poems I could include—how often I could stop time, in effect—before I needed to move the story forward.

It took much trial and error for me to see how many poems I could include—how often I could stop time, in effect—before I needed to move the story forward.

Poetry and plays have the power of the human voice in common; they were originally meant to be sung. Poems and plays often bring us right into the present tense with a different immediacy from that of prose. When we first did auditions for the role of Max, it gave me joy to see how viscerally actors of his same generation connected with his poetry, how easily his language held an audience, how three dimensional his words already seemed, and how much his voice bounded into the present moment. Max wrote, “Even present tense has some of the grace of past tense,/what with all the present tense left to go.”

*

What do I mean when I say that Max turned his teachers into students? On an abstract level, Max was so wise, so well-read, and so in-your-face talented that any teacher who was observant could see plainly that Max was a colleague rather than a receptacle for knowledge. An essay he wrote when he was twenty about Zen Buddhism, poetry and comedy could easily have been written by a seasoned poet of eighty.

I know that venerable poet-teachers like Lucie Brock-Broido swapped manuscripts with Max, and Max used to visit Louise Glück to talk about poetry non-stop for days. Max’s talents as a teacher went beyond knowledge. He had a deep sense of reciprocity. If they would let him, Max would encourage and mentor his teachers. Within two months of knowing me, he asked to read my poetry. I am primarily known as a playwright, though I’ve written poetry my whole life, and Max somehow divined I had secret poems stashed in my desk and asked to read them.

In my early twenties, I’d had my poems rejected enough times that I had become a recluse about sharing them. I continued to write them privately and used them as fodder for my plays. Not only did Max ask if he could read my poetry, but he also asked me if he could circulate them for publication, which he did, leading to my first published poem as a grown-up, published by his friend Elizabeth Metzger (author of the recent Lying in, who at that time also edited the Los Angeles Review of Books). As if that was not enough, Max continued to parry off the wall propositions for a playwright who used to have a fear of public speaking, he asked me to read my poems aloud to an audience. And I did. Max was an extroverted poet (usually an oxymoron) who relished the performance of his poetry.

The first time I saw Max read at 13th street repertory theater, he had just won a poetry competition judged by Jean Valentine. That competition led to the publication of his first chapbook, Aeons, and all his friends and family turned out to see him read from it. People poured into the cramped theater, in a pre-pandemic vision of how life used to be when people wanted to get close to each other while hearing poetry out loud.

Max wore a pink kimono and read in a booming voice. He had no need for a microphone. His poetry performance style was unique and theatrical (watch him perform his poetry on Youtube, his live performances are magnificent, and funny). At 13th street repertory theater, he circled in quasi-Rabbinical fashion, to include the large audience packed both in front of him and behind him on the stage.

Not long after that reading, Max went into emergency surgery because a tumor on his lung was “acting up”, he’d told me on a voicemail. When his voicemail was full, I wrote him a poem instead:

An automated recording from a hospital near you

An X-Ray of your soul shows

a general radiance

While the scan of your breath

shows only poetry

Waiting on the biopsy

of your imagination

But we suspect it cannot be contained.

Your body cannot contain you.

You’re way too wide for that.

And if there is a Jewish heaven,

it is here, on earth,

on thirteenth street:

you, shouting poetry

in a crowded room

circling,

and wearing a pink kimono.

*

Not only did Max teach me how to read my poems out loud, and how to share them with others. He also taught me, and he taught so many others, how it might be possible to face illness with blazing generosity, love, and poetry. For as long as I knew him, Max was obsessed with the question of ritual in a secular age. He himself was deeply occupied with metaphysical questions, even though he was entirely beyond dogma.

For me, theater is an embodied form that can create a ritual container for poetry.

For me, theater is an embodied form that can create a ritual container for poetry. I added the words “a ritual’ as a subtitle of the play Letters from Maxwhen we were in the last week of previews before opening night. With dread, I had started to imagine reviewers streaming in with a clinical gaze, when I knew that many in the audience would still be in very real mourning.

How, I wondered, could the concept of a review be compatible with an experience of a ritual? Rituals call out for engagement and enactment on the part of the audience. A stepping towards rather than back, an invitation to catharsis, which is impossible to have while maintaining critical distance.

It turned out that my fears were unfounded, and the audiences who have come to encounter the play seem to intuitively understand the ritual invitation. I once asked Max in an interview: “How can the poetry world reclaim the world of the spirit in a secular age?” And Max answered:

“I can’t think of anything… I could disqualify as the spiritual centerpiece of a poem. I don’t think the spiritual world needs to be claimed or reclaimed by anyone or anything. Let religion lay hands upon it. Let secularity lay hands upon it. But let the hands be gently laid. Let anything that clasps offer the kind of prayer it wants to pray. Let this all be poetry.”

Let this all be poetry!

*

Max Ritvo’s two books of poetry, The Final Voicemails, and Four Reincarnations are available from Milkweed editions. Letters from Max, a ritual (based on a correspondence with Max Ritvo runs at Signature theater through March 26th. You can purchase tickets here.

Sarah Ruhl

Sarah Ruhl is a playwright, essayist and poet. She is a MacArthur “Genius” Award recipient, two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist, and a Tony Award nominee. Her book of essays, 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, was published by FSG and named a notable book by The New York Times. Her book Letters from Max, co-authored with Max Ritvo and published by Milkweed Editions, was on the The New Yorker’s Best Poetry of the Year list. Her plays include For Peter Pan on her 70th Birthday; How to Transcend a Happy Marriage; The Oldest Boy; Stage Kiss; Dear Elizabeth; In the Next Room, or the Vibrator Play; The Clean House; Passion Play; Dead Man’s Cell Phone; Melancholy Play; Eurydice; Orlando; Late: A Cowboy Song, and a translation of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. Her plays have been produced on and off Broadway, around the country, and internationally, where they’ve been translated into over fifteen languages. She has received the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize, the Whiting Award, the Lilly Award, a PEN award for mid-career playwrights, the National Theater Conference’s Person of the Year Award, and the Steinberg Distinguished Playwright Award. She teaches at the Yale School of Drama, and lives in Brooklyn with her family.