Poet Sara Deniz Akant Talks Uncertainty, Turkish Identity, and Embracing Cringe

Peter Mishler Talks to the Author of Hyperphantasia

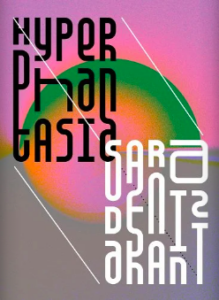

For this installment in a series of interviews with contemporary poets, contributing editor Peter Mishler corresponded with Sara Deniz Akant. Akant is a Turkish-American poet, educator, and performer. She is the author of Hyperphantasia (Rescue Press 2022, NYT Best Books 2022), Babette (Rescue Press 2015, winner of the Black Box prize), Parades (Omnidawn 2014, winner of the chapbook prize), and Latronic Strag (Persistent Editions 2014). She has an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a PhD in English from the CUNY Grad Center. She teaches poetry as Professor of the Practice at Tufts University and co-curates the Kan Yama Kan reading series in Brooklyn.

*

PM: What is the strangest thing you know to be true about the art of poetry?

SDA: At the moment? The way it runs on the fuel or fumes of friendship, relationships, the listener on the other line, what Sartre called the hell of other people. This, despite the old romantic idea that writing is a lonely act. I always want the door more tightly closed, the music turned down, the space furthest away from light or sound. But I’ve also realized I only need this distance to feel closer to whatever it is I am trying to shut out. So the point of the poem is to connect to that sense of dread or exposure. And somehow this paradox works. It makes me more myself than less.

PM: What did you feel more drawn to when working on Hyperphantasia: reflecting on and understanding past events or exploring how the past affects a present state of being?

SDA: Hyperphantasia has more of “the present” caught on tape than anything else I’ve written. During the pandemic, I started writing a poem a day with one friend, and then another, so I was generating lots of immediate, angsty, journalistic poems. Although my poems are always performative, those ended up being especially so. I had a specific reader in the Google doc, someone I knew well and trusted with experiments done haphazardly.

I was also lucky enough to have a space to regularly read my bedroom drafts out loud, because I started an in-person, outdoor reading series, and the open-mic events had me writing with a sense of drama—like continuously jumping off a bridge or taking off my clothes in public. It’s a style I always had a tendency toward, even as a kid, but I hadn’t quite embraced it on the page. Sometimes the materials I drew on were from the past—the desire to connect back to my family and their language, for example. But the energy behind me was a daily-presence energy.

PM: Did you experience any ambivalences or uncertainties about a style that advances a certain kind of risk, freedom, or rawness?

SDA: Totally. When I first put these poems together, I was on a sort of high, in part from writing quickly, or writing without much preciousness around the idea of a “good poem,” and in part because I wasn’t imagining any of this being published on a page. There was an irreverence and desperation I was going through that year, which made me feel very far away from the life I was supposed to be living on paper. I wanted to throw away the idea of grandeur or beauty in literature as well as in daily living. Later, when I saw the book in print, I struggled to accept the language I had let loose into the world. I didn’t open the first box of books for weeks.

It was only after participating in tons of launches and readings this past year that I was able to build a more critical understanding around what initially felt cringe—attention-seeking profanities and personas, diary-entry poems, all my fragments of form. Reinhabiting those voices and performing their words post-publication allowed me to embody my aesthetic choices in a new and satisfying way.

PM: How would you describe or personify the speaker? Did this speaker reveal anything about a part of yourself?

SDA: The speaker is always slipping behind a mask, always playing with a now-you-see-me, now-you-don’t kind of multiplicity. Sometimes this is a fantasy femme figure, named Phanta—sometimes it’s a narrating voice that speaks to, about, or around Phanta—and sometimes the speaker is some slant version of me. Especially in the longer poems, I imagine a distorted, cartoon image of myself, standing on the stage that is the poem, and performing a series of personalities or personas that, for some reason, I felt my imagined audience expected me to perform.

This is where I read complex feelings about race and gender in the book. Like how the poems glitch around a few somewhat superficial markers of being Turkish—having exoticized nipples, or a big nose, or the idea of not only collecting white girls, but also being able to become them. As the collection goes on, these markers become more confusing and surreal, but in a way that matches my lived experience more accurately. Like the nose gaining a pair of feet and following me around, or the word “oriental” with parasites I can’t quite process, or my American mother making a fat-free Turkish yogurt soup for dinner.

So the speaker is built around a desire to continuously shift and play with these markers just enough to stay illegible. Ideally, illegibility has the potential to work against the stable or digestible narratives of raced and gendered identity that I felt the world wanted from me, especially at that time.

PM: Was there a point in your writing life where you intentionally embraced illegibility or understood what illegibility could mean to you? Were there artists who guided you along this path?

SDA: I always struggled with the feeling of being illegible, and I formed myself around that feeling from an early age. In poetry, I felt seen by Keats’ idea of “being in uncertainties,” but it took until my late twenties—a fair amount of time after I began writing poems—to think of uncertainty as something interesting, something connected to a larger experience in the world. And it took even longer to link illegibility to race, gender, and ethnicity.

I definitely needed exposure to writers and artists who dealt more closely with questions of identity—Theresa Hak Cha, Cathy Park Hong, Meena Alexander, Audre Lorde, Homi Bhabha, Malik Gaines, to name just a few—in order to see my resistance to being fully understood as more than simple teenage angst. But really, understanding my impulse towards illegibility was as elliptical as anything else. It was formed through reading, yes, but also sofa and dinner table conversations with friends, learning to listen better, and being less fearful overall.

PM: What is a moment, image, or memory from your childhood that you think presages that you’d become an artist in your adult life?

SDA: I don’t remember how old I was, but one summer, I would sneak out of the house and disappear through what I called “the woods” into a neighbor’s yard. I was visiting a squirrel that had died next to a tree, and I’d crouch over its body to watch that slow decay. My self-imposed task was to repeatedly whisper to the squirrel a phrase I’d heard somewhere—ashes to ashes, dust to dust—words I believed would help its journey from body to ground.

What I connect to poetry here is the repeated ritual and tending to a thing—plus the act of witness tied to language—plus a belief that language has the power to tie nature to our actions. The squirrel invited me to a sort of obsessive incantation, and I still try to embrace these kinds of obsessive language acts.

PM: Could you talk about your early drafting?

SDA: In the case of Hyperphantasia, early drafting happened in the shared Google doc. But most often I was pulling from my two favorite places to record language, sounds, or notes for poems. First, the margins of books, or anything else I am listening to or reading—which is certainly not always great, or even literature—and second, my iPhone notes, which is writing that happens in bed, at dinner, or on public transport, and stems from an unpredictable energy or mood. From there, it’s a matter of world-building—figuring out the narrative or the thing I need to say—and animating that from within or between the lines or language.

I always struggled with the feeling of being illegible, and I formed myself around that feeling from an early age.

PM: Could you talk about when in the writing you decided to specifically include your “References and Notes” section? Was this something you imagined you’d do all along?

SDA: Since the poems were written in that daily way, I certainly wasn’t thinking about it from poem to poem. But when I put them all together, I knew there were at least a few poems where a line or phrase had to be referenced—lifted language from literary sources or people I didn’t know, often unintentionally inserted into my own voice. And I wondered what would happen if I treated the more hermetic and intimate references from family and friends as equally important.

What sort of meta-world might that build or allow the reader into? My ultimate goal was to make these references themselves into their own poem—a sort of coda or “afterward” for the book—but that didn’t end up happening in the end. I still love the idea of developing metadata poems that run beneath, above, or alongside others in any sequence, collection, or book.

PM: What worlds would you say the poems exist in—is there a kind of cosmologic organization?

SDA: Oh, articulating different worlds inside the book could be fun.

So there is the manic robotic doll performance world of clown tears and neon lipstick and googly eyes. There’s the underworld of perverted growth and insidious bugs and rotten carcasses, sepia-toned. There’s the over-world of sober narration and direct statements made almost in earnest. There’s also “desperation living room,” which is full of pandemic anxiety, gendered sadness, relationship fear, and infertility angst. There’s a related world of anger, in which the speaker tests out anger as a tone or form, bratty-child vibes.

There’s also the cartoon world of fake marriages and botched weddings and imaginary castles and plastic glamor. There’s a dream world where half-formed characters like Sylvie and Chandler and a bunch of unborn children roam around, and it’s also kind of fancy and pretty in there, like a haunted mansion. There is the world of origins, and the circular telling of family origin stories, with scientific facts that don’t add up.

And none of these worlds are distinct so much as layered through the book. Most poems straddle at least a few, or some, or all.

PM: Could you talk a bit about two words in your work: “infestation” and “disgusting”?

SDA: I want to say my obsession with infestation began with a cockroach experience I had circa 2016-2018, and my subsequent desire to write about it in an interesting way. But I’d also say that the sensation of infestation—the body, the home, or any demarcated space being slowly taken over by an insidious “other,” or a quietly powerful force—is so primal, so haunting, so ancient, so colonial, so real and transformative in day to day life—that it has been under my skin since childhood and will live there forever, just like roaches themselves will always live in our homes. So infestation dreams, bugs and their becomings, the psychic experience of watching something multiply uncontrollably—that will always be an undercurrent in my poems.

What’s fun is the way that the leftover trash begins to speak to itself. The rejects are gathered on the page and start having a weird conversation.

As for disgust, I associate the word with an attempt to externalize the feeling of how I am perceived, or to internalize how I perceive myself. It has to do with being gendered as a woman, feeling “other” in both body and culture. Both words attempt to handle the feeling of being monstrous, or being made to feel monstrous, in the world.

PM: Do you turn outward toward the world for a time before delving back into poems? Do you work on new poems having finished a collection?

SDA: I’m always working with remainders—the leftover lines, documents, narratives that didn’t fit elsewhere—and I can’t deny that poems and books often begin as outgrowths of other poems and books. What’s fun is the way that the leftover trash begins to speak to itself. The rejects are gathered on the page and start having a weird conversation. Then fresh language creeps in, and that experience of stalking the present through the past becomes sort of addictive. In better moments this feels like a spiral I hope moves upwards instead of backwards—a practice of circular return with punctuated moments of flight.

Most of the time, I think I’ll never write again. But I also admit there’s almost always a type of writing going on, whether that’s just in text messages or grocery notes or ugly photos on my phone. If I’m not writing at all, I begin to lose sleep.

___________________________

Hyperphantasia is available now from Rescue Press

Peter Mishler

Peter Mishler is the author of two collections of poetry, Fludde (winner of Sarabande Books' Kathryn A. Morton Prize) and Children in Tactical Gear (winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in Spring 2024). His newest poems appear in The Paris Review, American Poetry Review, Poetry London, The Iowa Review, and Granta. He is also the author of a book of meditative reflections for public school educators from Andrews McMeel Publishing.