Poet, Artist, Erotic Muse of Mexico's Avant Garde: Rediscovering Nahui Olin

On the Life and Times of a True Iconoclast

In Diego Rivera’s La creación, Nahui Olin sits among a gathering of figures that represent “the fable,” draped in gold and blue. She appears as the figure of Erotic Poetry, fitting for what she was known for at the time: her erotic writing and sexual freedom.

Olin—a painter, poet, and artists’ model—was known throughout the 1920s and 30s for her intense beauty; huge green eyes, golden hair, and an all-engulfing stare. But her image has been practically erased from the lore of that post-revolutionary time. Her piercing eyes aren’t recognizable unless one is familiar with her face, and the myth that surrounds it: of a woman who reveled in her own beauty, who painted portraits of herself with her many lovers, and who was eventually shunned by society and died, decades later, in the house that she grew up in, alone. Now, a new generation is revalorizing her story.

On a warm afternoon this winter, I walked along Calle República de Uruguay in the La Merced neighborhood of Mexico City to the La Merced Cloister, for which the neighborhood is named. It is a large stone building, unremarkable from the outside; inside, it remains of one of the most beautiful monasteries in Mexico.

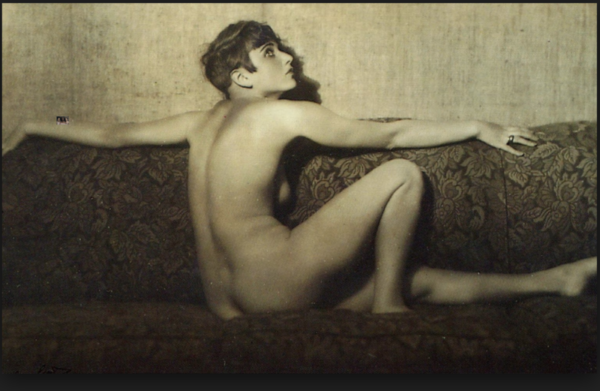

It was in this monastery that Olin lived with her lover Dr. Atl in the 1920s. Their relationship was the talk of the town—she, a young divorced woman, posed nude for artists like Diego Rivera, Edward Weston, and Antonio Garduño; and he, a much older man, activist, scholar, and volcanologist, was beginning a national school of art from within the old cloister. Both were early members of the Unión Revolucionaria de Obreros, Técnicos, Pintores, Escultores y Similares, a school of artists working to forge a new national identity after the Mexican revolution.

Olin’s life is now being reexamined, in part, due to the work of journalist Adriana Malvido, who wrote a recently reissued biography of Olin, and art collectors like Tomás Zurian, who have curated shows of Olin’s paintings decades after her death, including an exhibition this year at the Museo Nacional de Arte. A movie about Olin’s life, Nahui, will be released in Mexico in 2019. As more details are uncovered, the connections between her past and our present are clearer; her feminist independence and sexual expression seem a jumping off point for current conversations about traditional women’s roles and how to break free.

*

Olin was born Carmen Mondragón in 1893 in what is now the Tacubaya district of Mexico City. It was then a separate town where diplomats like her father, General Manuel Mondrágon, kept second homes in lush meadows surrounded by creeks and trees. Mondrágon spent her adolescence in France because her father—who designed Mexico’s first semi-automatic rifle—had business there, and the family was later exiled to Europe after his involvement in a coup against President Francisco Madero.

Photo courtesy of Ava Vargas

Photo courtesy of Ava Vargas

In 1913 Mondrágon married a handsome, intellectual painter named Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, who later became a solemn figure in the Mexican Muralism movement. They moved together to Paris where they met artists like Matisse and Picasso and the writers André Salmon and Jean Cocteau. Their marriage was unhappy—Mondrágon accused Rodríguez Lozano of being closeted, and they had a baby in 1914 who died very shortly after. Rodríguez Lozano later claimed the baby’s death was Mondrágon’s fault, which her family denied.

Olin’s letters are erotic and confident, far from the conservative social norms Mexico had recently left behind.

In 1921 they moved to Mexico City, where they split ways. Mondrágon began modeling for Rivera and other artists and painting scenes of daily life. In July 1921 she met a man named Dr. Atl at a party, which Malvido documents in her book, Nahui Olin: La Mujer del Sol, through the words of Atl’s diary from that night:

I came back to the house from a party at the Señora Almonte’s home in San Ángel, with my head alight and my soul aflutter. In the midst of the swaying crowd that filled the rooms a green abyss opened before me like the sea, deep as the sea: the eyes of a woman. I fell into this abyss, instantly, like a man who slides off of a high rock and rushes into the ocean.

Atl and Mondrágon began an intense creative relationship. She moved in with him in the Merced monastery, where he was beginning his school. He was known for painting volcanos and landscapes with a new paint he invented, and began to draw many portraits of her lounging, reading, or nude. She wrote poems and painted scenes of weddings, cemeteries, circuses and bull rings. They wrote love letters back and forth, which Atl later published in his autobiography. Hers are erotic and confident, far from the conservative social norms the country had recently left behind. She wrote in one letter,

…I know that my beauty is superior to all of the beauties you could find. Your aesthetic feelings were brought out by the beauty of my body – the splendor of my eyes – the cadence of my walk – the gold of my hair, the fury of my sex – and no other beauty could take you away from me…

They had a passionate romance that became the talk of this newly liberated Mexico partly because, as photographer Edward Weston noted after walking with them, “it seemed everyone knew Atl.” Atl was born Gerardo Murillo but changed his name years before to Atl, the Nahuatl word for water. In 1922 he gave Mondrágan the name Nahui Olin, which is a concept from the Aztec calendar that signifies the fourth regenerative movement in the cycle of the cosmos. In 1922 she published her book first book of poetry, Óptica cerebral, which Atl illustrated, under her new given name, and never responded to Mondrágon again. In her poem “Insatiable Thirst,” she wrote:

My spirit and my body are always mad with thirst

for these new worlds

that I go on creating without end,

and of the things

and of the elements,

and of the beings,

who have ever new phases

under the influence

of my spirit and my body which are always mad with thirst;

unquenchable thirst of creative restlessness….

*

Their creative lives continued for the next year in the monastery, but the freedom Olin and Atl embraced began to fade as jealousy edged in. Atl received many students, artists, and people interested in his work, and Olin began to distrust his relationships with other young women.

Atl wrote in his diary that one day Olin tried to push two young women who had visited him off of a balcony. Another night he woke up to her, naked, pointing a revolver at his chest, which she shot into the floor in five loud rounds after he grabbed her arm.

“To the relations that Atl had with other women who visited La Merced, Olin did not respond with the expected submissive silence.”

She went public with her anger too, hanging a note on his door for all of the neighborhood to see, which accused him of sleeping with other women. Malvido notes, “to the relations that Atl had with other women who visited La Merced, Nahui did not respond with the expected submissive silence.”

In an October 1923 interview with El Universal Ilustrado, Atl was asked if he would ever marry a writer. He said, “I consider marriage a fundamentally absurd aspect of society… although a female writer may write well, life becomes insufferable after five minutes with her. I am convinced and am sure that this is how the majority of men think, that life with a woman is a constant contradiction; with a literary woman it would be a constant catastrophe.”

One week later El Universal interviewed Olin, and she replied that she would never marry a man, “And even less an extravagant painter or a mediocre writer, because they are already married to the obsession of glory and most of the time they are not worth it, they are husbands of vanity.”

Malvido mentions the artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, who said of Olin and her contemporary Guadalupe Marín that “their scandals marked an entire era” in Mexico’s burgeoning bohemian movement.

Olin was a scandal because she stood up for herself. She never showed guilt for her nude modeling or open sexuality. She made it clear that she was a free woman who would make her own choices. I met up with Malvido in Mexico City to talk about the interest she’s seen recently in her research on Olin’s life, and she said that Olin’s message is newly resonant today.

“She’s saying, ‘My body is my body.’ I think that’s the connection that she has with today. Millennials are connected with her language … the women’s movement, #MeToo. That is exactly what she was talking about. What we hear people talking about today is what she was claiming,” she said.

Olin eventually moved out of the monastery to her own rooftop apartment, in what were then considered maid’s quarters. She continued to paint and model—supporting herself as she did throughout her life by teaching art in Mexico City public schools—and promoted her work by organizing her own gallery openings. At an exhibit of her nude photographs in 1928, she made sure to invite diplomats, along with artists and socialites.

“She invited the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Education, and they went,” Malvido said. “They are in the book of visitors. That’s incredible.”

Then, in 1929, Olin met a Captain named Eugenio Agacino. She fell fast in love. She went on tours with him to Cuba and Spain, and when she stayed behind she would go to Veracruz each month to meet him at the port.

She painted portraits of them embracing in different parts of the world—over the Atlantic, in Cuba, in New York, sometimes nude together and always with matching, enormous eyes. This love affair continued until 1934, when Agacino suffered poisoning from bad seafood, and died. It is said that Olin still went to the port in Veracruz after she heard the news, because she could not believe that he was gone.

Olin had one last show that year and published her second book of poems, Energía cósmica, in 1937, but she began to spend more time away from the public eye. By the 1940s she had receded into herself and separated completely from her former public life.

*

In the late 1930s things in Mexico were also changing. The country, and the world, slid into more conservative times. The Great Depression and World War II brought austerity and fear, and the push for national reform through art and radicalism was replaced by more conservative ideas.

Olin was getting older, too. It’s believed that she became depressed after Agacino’s death, but aging could have also played a role in her separation from society.

“I have no age. Passion has no age. I am all intelligence and all love.”

She had once written to Dr Atl, “I have no age. Passion has no age. I am all intelligence and all love. Women are only the age of their passion in bloom. When that flower wilts, the woman dies.”

She continued to see herself as a young woman even later in life, as Malvido recalls Olin’s great nieces telling her. They would accompany Olin after she picked up her teachers’ paycheck, she would take the money straight to her favorite French restaurants to eat the food she had loved as a child. Her nieces say she still saw herself as a young woman and made herself up with the same lipsticks and smokey eyes that she always had.

“That’s when they started to call her crazy because she she was not pretty anymore,” says Malvido. “It’s very cruel. She lost the prettiness that she had, so people didn’t need her anymore. I mean, that’s my interpretation. So they dropped her and said she’s crazy.”

*

The monastery is now boarded up. There is one entrance on the side, covered by a large piece of spray painted, weathered wood. I walk by shoppers milling about on their way to the La Merced market, where people from all over the city have come for wholesale goods since before Olin’s time, from dried fruits to silk and cotton, flowers, meat, and spices. It’s become another stretch of stone wall in this busy, stall-strewn street.

Like the rest of her story, this part of her life has not been entirely erased, just hidden from view. With time, perhaps, we will be able to see inside once again.

Claire Mullen

Claire Mullen is a radio producer and writer currently based in Mexico City.