Poet and Translator Dong Li on the "Common Tongue of Poetry"

Peter Mishler Talks to the Author of The Orange Tree

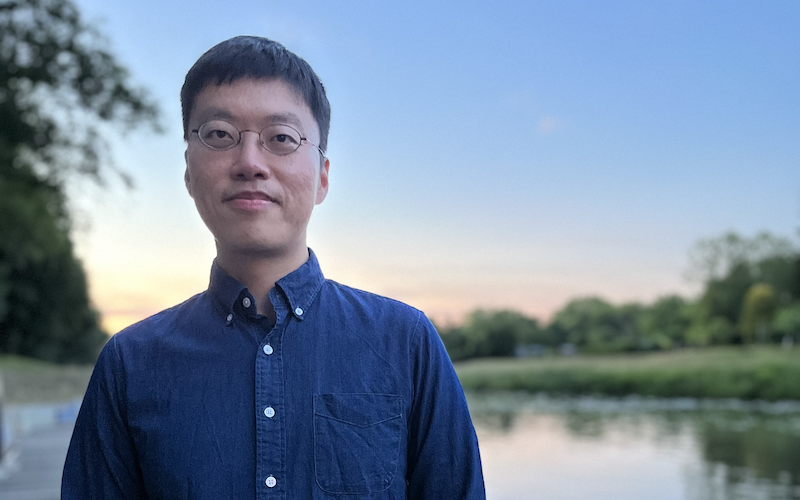

Dong Li is a multilingual author who translates from the Chinese, English, French, and German. Born and raised in China, he was educated at Deep Springs College and Brown University. His full-length English translations from the Chinese include Song Lin’s The Gleaner Song (Giramondo & Deep Vellum, 2021) and Zhu Zhu’s The Wild Great Wall (Deep Vellum, 2018). He has received fellowships from Akademie Schloss Solitude, Camargo and Humboldt Foundations, MacDowell, PEN/Heim Translation Fund, Yaddo, and others. His debut poetry collection The Orange Tree (The University of Chicago Press, 2023) is the inaugural winner of the Phoenix Emerging Poet Book Prize.

*

Peter Mishler: Is there a moment, image, or memory from your childhood or youth that somehow hints that you’d write poems as an adult?

Dong Li: I started poetry late, as I was discouraged to pursue creative writing in school back in China. American English gave me a second chance. I was enrolled in a tiny cowboy-philosopher school in the Californian desert. I felt intensely the limitation of my language abilities and practical skills in a seemingly harsh landscape. I remember walking in the desert and lying flat on the lonely highway that cut through it. I spread my fingers to grab onto the concrete as the sky became overwhelmingly close and started to shift. The clouds became a godsend and carried my first poems.

PM: What would you be willing to share about these first poems?

DL: One of the few real poems that came out of these first clumsy, albeit earnest, attempts was titled “To Cloud.” The clouds became the capitalized singular “Cloud” without an article, as if I were addressing a living thing. It was indeed alive and a friend during these grueling years, when my face became smeared by sand and stars in the increasingly less surreal desert environment. A time for my initiation, in which I relied on the sky for the dial of the day. More than a wall that echoed back my anxious projections, “Cloud” highlighted the distance between words and feelings, while accentuating the affinity between the “you” and the “I” in the poem. “Cloud” was the reflexive addressee “you,” from which the “I” was slowly apart. I was trying to emulate Lorine Faith Niedecker and her “condensery,” which resulted in the poem, but realized that the “I,” my poetic child, wanted to grow out of that early influence, so I wrote a speech in prose about my family history, which sowed the seeds for this collection, The Orange Tree.

PM: Did you feel a pull, urgency, or anxiety that drove you to write this prose speech?

DL: As the only PoC and foreign student in my class, I wanted to close the gap of misunderstanding by drawing in my less-privileged familial context. I wanted to share a sad story, hoping to soften the rough edge of my encounter with this utopian community. I wanted to leave the critical and poetic shield aside and talk unprotectedly. I wanted to see whether a switch of the genre gears would strengthen my grasp on American English. I wanted to hold the child tottering in a new language and the receding Chinese self in both arms. As I knocked myself out to piece the speech together, it felt like a gestation overdue. I reverted to the pantry of my survival word-kit and ventured to cook up a concise and cohesive narrative in irreducible sentences. I wiped away the invisible tears after each period. As I read out loud my first draft, I heard a sound, so familiar and yet far away, eerily mine and more than mine. It did not profess to be poetry. A revelatory moment: Perhaps poetry was something that recognized its unpredictable milieu and reclaimed its sound.

PM: Do you have artists in your family? What were you drawn to in your reading and writing in China?

DL: My mother’s brother, the youngest and only surviving male child of the maternal family, is a painter and teacher. He was among the first group of students that went to college in 1977 when college education was reinstated after a decade of hiatus due to political turmoil. All the family resources were poured into the brother’s education and wellbeing. Stripped of educational opportunities, his six sisters were often forced to skip school and take on knitting work to support him. I was averse to this kind of treatment, but was not mature enough to understand the sisters’ acceptance of their deprivation.

I was less interested in conventional literature that lauded such sacrifices and estranged love. Literature from a distant age or place seemed an exception, whose new context itself was liberating. I was drawn to the interior depth of women and their work. In the little space afforded them, they talked back and forth and fought and formed bonds between the stove and the washing board. Kitchen gossips turned into giggles; courtyard dances cheered up dispirited disputes. It was joyful for me to use writing to get a glimpse of the sisters’ little freedom theaters. That joy presumed, for my younger self, a sense of secret knowing. Still, it felt restrictive to fictionalize names and use the language the family could read. Another language turned out to be the easy remedy.

Poetry is everywhere and everybody has it. Often we direct our deepest feelings toward this unspeakable thing and call it poetry. Often we don’t give ourselves permission to speak it out loud. But when we do, we feel utterly alive.

PM: What was that like for you, to simultaneously experience a new country and begin your creative work there?

DL: It felt like seeing the child of me trying to stand up for the first time, knowing that it was left alone to fumble and find its bearings in the new language. It could grab onto the invisible hands of memory, but they would pull it back to the old strictures that it had just escaped from. The bright days of curiosity collided with the restless nights of unknowing. The child had to go both ways, like a small tree plant. It fingered the wind that shaped the music and mores of its surrounding. It broke up the tough soil that sustained and stimulated its development. Light was essential. Isn’t language always the light that launches us into the relational pool of living? I owe my courage to the desert. I was forced to articulate in a verbal community. I dug dirt. Inchmeal, the child stood up and babbled in joy. That’s where I began.

PM: What was the experience like for you to write so many different kinds of lines in this book? How do you see these forms in relation to each other, now that you’re able to look at the collection as a whole?

DL: Much like my experience in the desert where tumbleweeds wilfully rolled, I stumbled and scratched myself everywhere as I scrambled to put this debut collection together. The poetic child of me, who was absorbing American English, was messing around, and wanted to try various things. In retrospect, this kind of unencumbered curiosity was part of the openness that entertained the possibility of numerous forms, but what determined the different kinds of lines was the material I gleaned from mostly the women in the family. I wanted the book to host the whole shebang, their ghosts and suppressed songs.

I was having a hell of a good time, exposing the material and experimenting with appropriate forms to accommodate it. I used words to layer the thickness of the poetic core, around whose orbit scattered forms surfaced and swung into a synchronized constellation. I was happy to forget myself in this windswept tale of invisible tears. The single-line statements of the title poem might be seen as a step after a strenuous step toward unveiling the scarred splendor of survival and continuum. The blank lines in the double-spacing of the same titular poem hope to give room to the dead who add weight and weather to the surrounding silence. Sometimes, the vertical form is a tombstone; other times, a playful reversal of the Classical Chinese reading custom. Sometimes, the poem lies flat to flatter the narrative flow; other times, the prose deceitfully prolongs the poetic pull. Aren’t poetry and prose siblings that fight during the day and get along at night? This family of forms intends to capture the fading faces of the now familiar material and delay their disappearance.

PM: “Is death the only family.” is such a strikingly memorable line early on in The Orange Tree. Can you talk about how and when you made this line?

DL: One of the factors that triggered the seed of the prose speech about my family history to sprout into this poetry collection was the death of my paternal grandfather. The news of his death was withheld by my parents for over a year until I returned to Chinese soil. They said that Grandpa, on his deathbed, preferred not to interrupt my studies in the U.S. Isn’t love a wound, often covered, or only revealed in aching ways? Death obliterated the gap of time between my parents and me, hurtling us into this unknown presence that strangely but tangibly united us. It was also this other sphere we stared at blindly, in tears. “Is death the only family.” is an impassioned existential query, but the period indicates an emphatic resolution. Like death, the integral question is paradoxically there and not there. This questing statement is closer to a graveyard that called for my visits and provided for my latent seed. As I wrote the line on American soil, the physical and linguistic distance eased my acceptance of Grandpa’s death, whose intensity nevertheless commanded a lexical transformation. The grief turned from a lake that kept pooling to a recurrent river that gathered what it loved. Soiled, I wrote along this longing course.

PM: When you are reciting poems from this book now during readings, do these same feelings arise or are they new feelings?

DL: I like my readings to share the same emotive latitude as the locale. I try to get a sense of the tempo and temperament of the events and select sections accordingly. Obviously, I cannot recite the whole book, so I translate each reading into a curated performance that echoes the collection. These same feelings ripple out from the recital and still ring true to its core. Before reading out loud from the page, I look around the room until I hear the poems from a distance, as if they came from the audience and their muted words. The griefriver widens its course. As my eyes take in the light reflected from these shared syllables, I know the collection will chart its ground of growing pains. The babbling child is ready to walk its own way. I let it go and follow what love dictates.

PM: Readers will find a short glossary following the poems in this book. When did you decide to include the glossary?

DL: After making a mess and then another bigger mess with the manuscript, I was looking for ways of taming the untamable, and I aspired to fail gracefully. I borrowed from the construction of compound words in German, which I was struggling with at the time, and created a list of words as section breaks. I culled almost all the words from the following sections and let them sit elbow-to-elbow. The pressure of leaving out the space between words led to a fresh look at them, both individually and collectively, gaining a new compressed velocity that was more conducive to reflection. These lists of compound words could be seen as condensed signposts that contained their own mystery or translations of poetry back into words that first brought the material into a meaningful and musical order. As the lists became more complex to mirror the gradual drop of punctuation in the corresponding sections, the collection came to a final contracting density that I felt needed an expansive release, so I decided to lay bare my method for the manuscript by assembling all the compound words in one place, which recalled all the sections and evoked the memory of reading and re-reading. I titled the glossary poem “in search of words,” in the hope that such a lexicon would give clues to the unannounced and unarmed words of love only poetry could briefly hold in the long ears of listening.

PM: Could you talk a little about what your day-to-day writing process or routine looks like?

DL: I don’t really have a particular process or routine. I prefer playgrounds over rituals. I juggle a couple jobs for my hungry belly and strive to live as simply as possible, so that I can have time to serve my curiosities and fiddle with my interests. I am lucky to have an enclosed writing space that carries ghostly echoes. I hang up postcards on the wall with clothespins and wear these items of love to the keyboard. My current laptop is a hand-me-down from Don Mee Choi, which reminds me of my first from the late C.D. Wright. I write with these debts.

PM: Would you be willing to share your most recent observations on the twin processes of translating other poets and writing poems under your own name?

DL: I believe all languages come from the common tongue of poetry, where they long to converge. Translation of other poets often uncovers the forgotten tributaries or the contrarian undercurrents of a language that keeps arriving at the shared source. From this vantage point, translators can see what’s already done well and what fails to push the page and is worth another shot. In short, they understand the context of poetry that resists the suppression of chronological history. Isn’t poetry what cannot get lost in translation? Isn’t poetry the only heritage language for the poetic child? When I write poems in American English, I don’t have the same baggage of a canonical tradition as a first-language writer. I absorb its light to show my wound but refuse to be assimilated. I hunger for all the radiance on this earth. Translation becomes a reference point of negative capability in an enlarged multilingual context. I write toward the approximation of this radiance. I used to be burdened by a responsibility for the poets and their poems that I translate. Now I shed my vanity and possessive armors to embrace the possibility of multiple versions and variations. In a similar vein, I forgo the ambition of mastery and steady my poetic ship of longing toward each light and lightning along the way. It is lovely for you to call the writing and translation of poems “twin processes.” They gestate in the same water and glow from the same wound.

PM: What is the strangest thing you know to be true about the art of poetry?

DL: Poetry is everywhere and everybody has it. Often we direct our deepest feelings toward this unspeakable thing and call it poetry. Often we don’t give ourselves permission to speak it out loud. But when we do, we feel utterly alive. We add our layer of skin to a language we embody and enact. We see our silhouette coming into focus in these familiar and familial words that go into and out of our body and give breath to our singular sound. There is lament on poetry’s retreat from the public into private spheres, but I look to its rediscovery and reemergence inside of us. In a reckless rain, we lean into the nocturnal neck of poetry. We fall on its back. And if we look hard enough, even the stinking fish sings.

_________________________

The Orange Tree by Dong Li is available now via the University of Chicago Press.

Peter Mishler

Peter Mishler is the author of two collections of poetry, Fludde (winner of Sarabande Books' Kathryn A. Morton Prize) and Children in Tactical Gear (winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in Spring 2024). His newest poems appear in The Paris Review, American Poetry Review, Poetry London, The Iowa Review, and Granta. He is also the author of a book of meditative reflections for public school educators from Andrews McMeel Publishing.